At the end August 2019, news about a statue of Ottoman Armenian Soghomon Tehlirian (who murdered Ottoman-era Minister of Interior and Prime Minister-Grand Vizier Mehmet Talat Pasha) being erected in the town of Maralik in Armenia caused indignation in Turkish media and public opinion.[1] According to the news, as depicted in the statue, Tehlirian strikes a heroic pose wielding a pistol and stepping on the severed head of Talat Pasha. Historically speaking, the Talat Pasha murder committed by Tehlirian was a part of the second wave of terrorism (1921-1927) perpetrated by militant Armenian groups against Turkish targets.[2] Hence, the Talat Pasha murder represents for Turkish society the transformation of anti-Turkish sentiment into violent action.

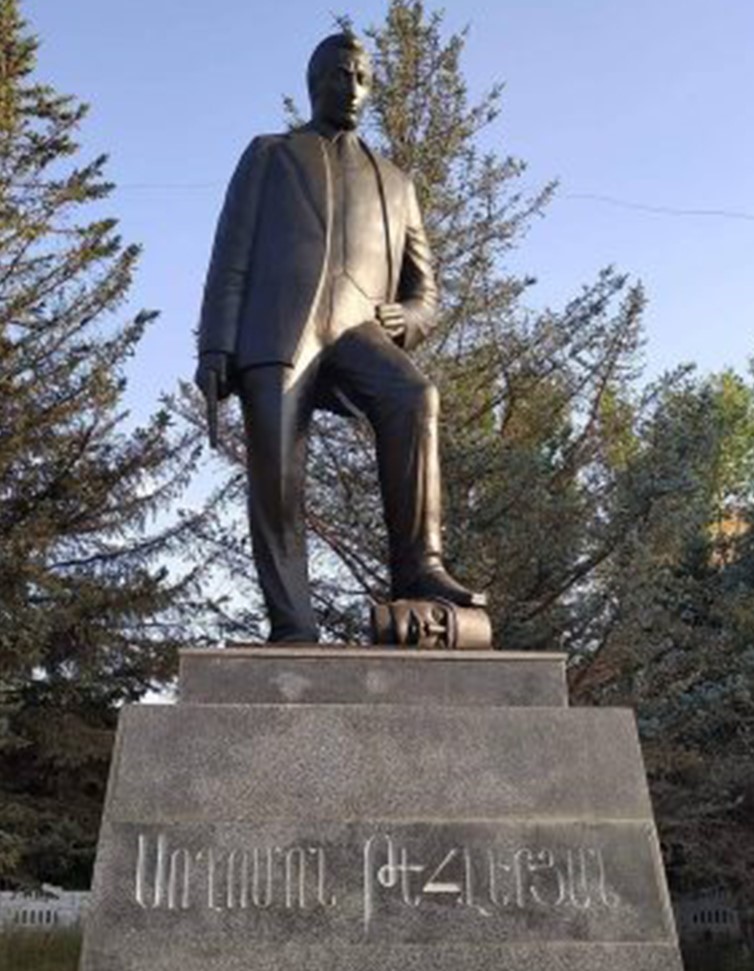

Research regarding the said statue reveals that it was not unveiled in recent times, but on 22 April 2015.[3] Armenian-sourced news published during and after the unveiling of the statue indicate that there is a difference between the statue during its first unveiling and its current state. One of the articles[4] indicates that what Tehlerian steps on is not the severed head of Talat Pasha but a piece of stone. However, the sculptor of the statue Samvel Petrosyan stated that he originally designed the statue with Talat Pasha’s severed head, by which he sought to express that no crime will go unpunished. However, according to Petrosyan, upon local officials’ objection on the grounds that “Europe would be disturbed” by this design, he was forced to switch the severed head with a piece of statue. Nevertheless, Petrosyan expressed his wish to have the statue exhibited according to his original design and his wish was apparently accepted by public authorities in 2018.[5] According to a recently published article in an Armenian news outlet, the Tehlerian statue was changed into its original, severed-head version as per the wishes of Petrosyan.[6]

The transformation of the statue into its severed-head version will be considered not only in European countries, but all around the world as the product of a barbaric mindset. In its current form, the statue legitimizes hatred, extremism, and terrorism with the approval of public authorities. By being displayed in the town square where even children can easily see it, the statue normalizes for everyone the sickly mindset it represents.

No matter what is being depicted as being stepped on, the unveiling of the statue of Tehlerian (a shady man who has been discredited by even his own son) with a state ceremony[7] points towards the existence of serious social problems both in Armenia and the Armenian Diaspora. Before delving into this issue, it will be beneficial to provide some information about both Talat Pasha and Soghomon Tehlirian.

There are major differences between the portraits of Talat Pasha drawn by nationalist Armenian historiography on the one hand and historical documents on the other. From what can be gathered from historical documents, Mehmet Talat Pasha (1874-1921) was confronted with a dire situation during the First World War: 1) Seriously lacking in combat readiness, equipment, supply lines in the standards of those times, Ottoman forces were being defeated by the enemy and many of them were perishing before even reaching the battlefield due to conditions of war and environment, 2) Armed revolutionary Armenian gangs were sabotaging the Ottoman army’s supply lines and colluding with the invading enemy forces, and 3) Ottoman Muslims were being subjected to the systemic massacres and cruelty of the Armenian gangs. In time, the idea emerged within the Ottoman government to relocate the Ottoman Armenians to deprive the Armenian gangs of the support they were receiving from the Ottoman Armenians either through sympathy or at gunpoint and to remove potentially troublesome groups from warzones. Despite this, Talat Pasha resisted this idea for a long time. Based on what he wrote in his memoirs, due to his resistance, Talat Pasha was accused by some of his collogues of neglecting his duties or even committing treason. However, the Van Rebellion that began in April 1915 demonstrated the severity of the situation, and he concluded that the Armenian relocation had become a matter of necessity.

On 24 April 1915, Armenian intellectuals and opinion leaders determined to be or suspected of being involved in gang activity were arrested in Istanbul and sent Ayaş and Çankırı near Ankara. Upon the continuation of Armenian gang activity, the Armenian relocation was put into effect on 27 May 1915. The Ottoman government made preparations for the relocation to take place within reasonable conditions and sent directives in line with these preparations. Talat Pasha himself had commissions set up to have officials who mistreated Armenians during the relocation investigated. Upon the conclusion of the investigations of these commissions, individuals found to be at fault were sentenced to various punishments, including execution. Despite all these precautions and punishments, tragic events took place during the relocation, and many Ottoman Armenians lost their lives due to war and environmental conditions, bandit attacks, intercommunal fighting, and the personnel and infrastructure inadequacy of the Ottoman Empire.

Yet, nationalist Armenian histography oftentimes completely ignores these historical data and puts forth a starkly different portrait of Talat Pasha. The threat that had been posed to the Ottoman Empire by the activities of Armenian gangs is downplayed and the armed attacks of the gangs are narrated as acts of self-defense. According to this narrative; in line with their paranoid distrust towards Ottoman Armenians and their Islamist or Turanist goals, Talat Pasha and the Ottoman government sought to cleanse the Ottoman Empire from its Armenian and Christian elements and carried out a premeditated policy of annihilation -in other words, a genocide. In this narrative, Talat Pasha is introduced as the “mastermind” of the alleged genocide. As such, over the years, Talat Pasha has transformed in Armenian perception into a man to be loathed, a villain straight out of cliché movies.

As for Soghomon Tehlirian (1897-1960), he murdered Talat Pasha on 15 March 1921 in Berlin by shooting him in the back of his neck. Put on trial after the murder he committed, Tehlirian confessed to his crime but expressed no regret throughout his trial. Tehlirian told the jury of the court that while in Erzincan in June 1915 during the Armenian relocation, he had witnessed the murder of his entire family and village by Ottoman gendarmerie and the raping of his sister, and that he was wounded but miraculously escaped from this ordeal. Tehlirian went onto to explain that, while dreaming, his mother told him that Talat Pasha was in Berlin and scolded him for still not having killed Talat Pasha. Tehlirian argued that he killed Talat Pasha after having “stumbled upon” him in Berlin. In other words, Tehlirian portrayed himself to the court as a victim of traumatic events, a man who survived only to exact revenge for his slain family and people.[8] After a while, it was not Tehlirian who was being tried in the court, but Talat Pasha and the Ottoman State. This reversal of roles was fueled by the anti-Turkish and Ottoman sentiment that had peaked at that time in the Western world. In the end, due to his past victimhood, it was deemed that Tehlirian had been suffering from temporary insanity when he murdered Talat Pasha. As if proving that there were no judges in Berlin, Tehlirian was released by the court in a travesty of justice. Today, it is argued that Tehlirian’s murder of Talat Pasha and his logic-defying release by the court served years later as a source of inspiration for the third wave of terrorism (1973-1986) perpetrated by militant Armenian organizations against Turkish diplomatic personnel and their family members.[9] With this incident, the killing of Turks through terrorism motivated by political objectives became a legitimate method for many fanatical nationalist Armenians.

However, documents acquired years later demonstrated that the story told by Tehlirian to the jury of the court in Berlin was a fabrication;[10] 1) Tehlirian had not planned the Talat Pasha murder by himself. Instead, he acted within Operation Nemesis launched by the Armenian Revolutionary Federation (ARF-Dashnaktsutyun) to primarily exact revenge for the Armenian relocation. The ARF had completely ignored its key role and fault in the deterioration of trust in Turkish-Armenian relations, had chosen to place the entire blame on the Ottoman Empire, and had sought to send a political message to everyone through a campaign of retribution. 2) Prior to murdering Talat Pasha, Tehlirian had in 1919 murdered Haroutiun Mugerditchian, a loyalist Ottoman Armenian, within the framework of Operation Nemesis. This means that Tehlirian was not an ordinary victimized Armenian, but an experienced assassin. 3) Tehlirian had left the Ottoman Empire in 1913 and settled in Belgrade where his father and brother resided to pursue an education in engineering. After the First World War started, he traveled to Tbilisi and joined Armenian volunteer units who were colluding with Russian forces invading Anatolia. Tehlirian only returned to Erzincan in July 2016, and based on available information, his father had not left Belgrade. As can be understood from all of this, it was simply not possible for Tehlirian to have suffered from the trauma that he told the court in Berlin.[11]

Consequently, the portraits of Talat Pasha and Soghomon Tehlirian painted by nationalist Armenian historiography does not reflect the truth. The statue erected in the town of Maralik/Armenia in 2015 therefore glorifies and heroizes a Tehlirian who was in fact a liar and a cold-blooded killer and terrorist. In this framework, the statue fails to be anything more than a source of provocation between Turks and Armenians.

The distorted historiography, the incitement of hatred, and the encouragement of extremism put forth through Talat Pasha and Soghomon Tehlirian is not an isolated incident. Various developments in Armenia and the Armenian Diaspora have served or continue to serve a similar negative function:

1) In May 2019, the remains of Gourgen Yanikian’ın (1895-1984), who had assassinated Turkey’s Los Angeles Consul General Mehmet Baydar and Consul Bahadır Demir in Santa Barbara/the US in 1973, was transported from the US to Armenia and buried in a military cemetery with a state ceremony.[12] This means that Armenia has treated a terrorist who murdered a neighboring country’s diplomats as a hero.

2) In May 2016, a statue of Garegin Njdeh/Ter-Harutyunyan (1886-1955) was unveiled in Yerevan with an official ceremony.[13] Despite having committed massacres against Azerbaijani Turks and being a Nazi war criminal, Njdeh is nevertheless treated as a national hero in Armenia. There is also a metro station, a public square, and a monument in Yerevan named in honor of Njdeh. Drastamat “Dro” Kanayan (1884-1956), another massacrist and Nazi sympathizer, is similarly commemorated and exalted in Armenia.[14]

3) There is a monument in honor of ASALA, an organization that murdered Turkish diplomats and their family members during the third wave of terrorism (1973-1986), in a military cemetery in Yeravan. Additionally, there is a bust in Yerevan in honor of Monte Melkonyan (1957-1993), who was one leading members of the terrorist organization and whose remains lay in the above-mentioned cemetery. A monument erected in honor of this terrorist organization in the city of Vanadzor “was opened with a liturgy conducted by the priests of the Armenian Apostolic Church, [… and] the video of this opening liturgy was shared by […] a TV company founded by the […] Church.”[15] That is, just like in the first example, terrorists who murdered a neighboring country’s diplomats are treated as heroes in Armenia.

4) On 17-30 July 2016, around thirty members of the Sasna Tsrer (Daredevils of Sassoun) organization wielding automatic weapons and rocket-propelled grenades stormed a police precinct in Yerevan, killed four police officers, and took hostages. Members of the organization demanded the release of Jirair Sefilian (Zhirayr Sefilyan), one of the leaders of the organization who is known to have partaken in separatist activity in the Nagorno-Karabakh region of Azerbaijan and who was arrested by the government of Armenia on the suspicion that he was preparing to carry out a coup d’état in the country. The members of the organization also demanded the resignation of then-President Serzh Sargsyan and the forming of a new government. While in other countries storming a police precinct and murdering police officers for political purposes is considered an act of terrorism, in Armenia, a significant portion of the people gave support to the Sasna Tsrer terrorists and carried out demonstrations in their favor. Moreover, this development was treated as an ordinary development within the politics of Armenia.[16] It seems that the taking up of arms in pursuit of one’s own sense of “justice” has become an established piece of Armenia’s culture.

5) The ARF is the most dominant organization within the Armenian Diaspora and is still an actor that must be taken into consideration in Armenia. Although the ARF has always marketed itself as the unflinching guardian of the Armenian people and Armenia, it has in fact acted as a nuisance for both Turks and Armenians ever since its establishment in 1890. Shortly after its establishment, the organization began to carry out acts of terrorism in the Ottoman Empire. The ARF played a key role in the deterioration of Turkish-Armenian relations due its use of excessive violence and its foolish adventurism in the name of an Armenian struggle for independence before, during, and after the First World War. Indeed, the first prime minister of the Democratic Republic of Armenia (First Republic of Armenia) Hovhannes Kajaznuni heavily criticized the ARF due to such faults (although, Kajaznuni also criticized in a sarcastic manner the Turkish side for what transpired during those times).[17] However, the ARF failed to draw lessons from the grave mistakes it had thus far committed, and carried on with its extreme conduct. After the 1960s, the ARF began to subject the Diaspora youth to systemic brainwashing against Turks and established the Justice Commandoes terror organization that carried out attacks within the framework of the third wave of terrorism. As known, this organization left deep marks in Turkish society with the deplorable attacks it carried out against Turkish targets, and thus further strained Turkish-Armenian relations. Ever since those days, the ARF has continued to act as the flagbearer of militancy both in Armenia and the Diaspora. An article titled “Who Is an ARF Member-Dashnakstagan” that was published in February 2019 in Asbarez (an ARF news organ) demonstrates that the ARF continues with a totalitarian mindset to place selfish party interests ahead of the interests of the Armenian people.[18] So long as this party continues to conduct itself with this mindset, it will continue to serve as a source of provocation in Turkish-Armenian relations.

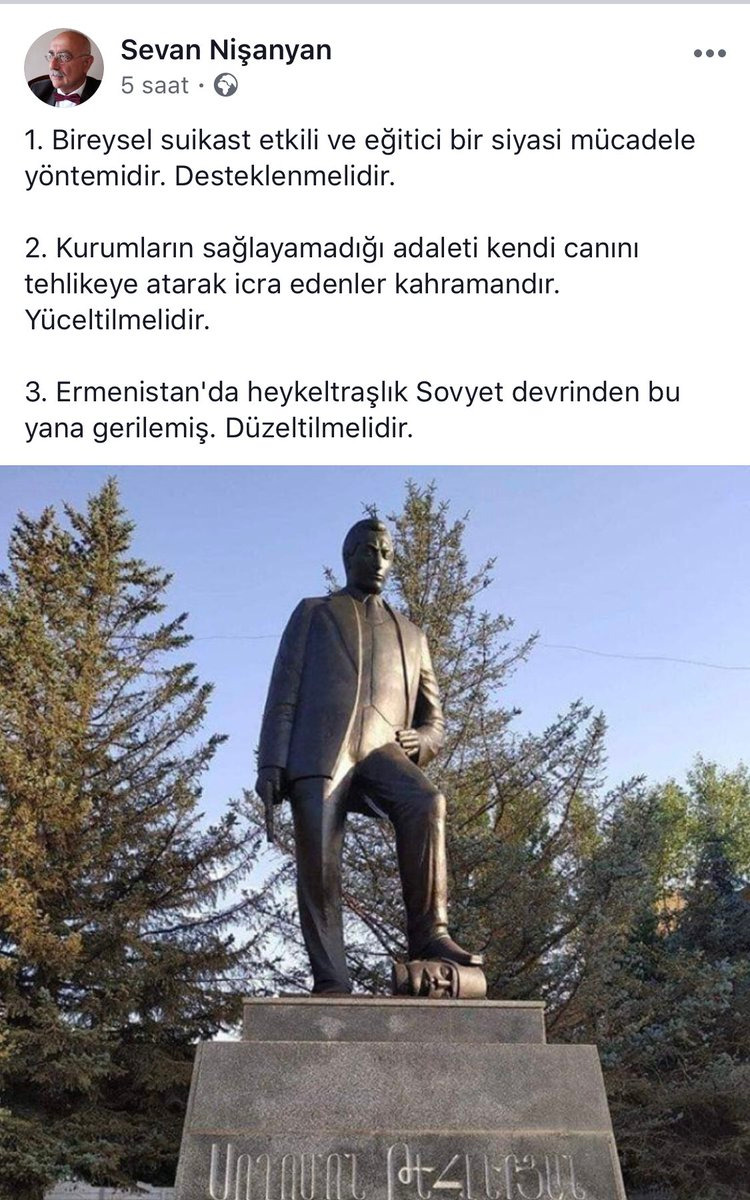

If we were to return to the original issue of the Tehlirian statue in Maralik, there have unfortunately been those in Turkey who have supported the extremism represented by this statue. Turkish Armenian author Sevan Nişanyan, known for his scandalous personality and sentenced to incarceration in open prison (which he later escaped from) for insisting on carrying out construction in a protected area despite having received a cease and desist order,[19] posted a comment on his Facebook profile on 25 August supporting the extreme views represented by the Tehlirian statue (please see the screenshot below). Despite receiving criticism from some Facebook users, Nişanyan did not back down and made statements legitimizing terrorism.[20] Although Turkish Armenians refuse to partake in the excesses of Armenia and Diaspora Armenians, such isolated incidents unfortunately do occur.

The 1915 Events and the related disputes continue to be a serious problem in Turkish-Armenian relations. There is a need for mutual understanding and will for reconciliation in other to overcome the tension and mistrust existing between the two sides. However, as can be gathered from what has been explained above, the legitimation of hatred, extremism, violence, and terrorism continues in an intense manner in Armenia and the Armenian Diaspora. Publications in Armenia and the Diaspora have always attributed the responsibility for the deadlock in Turkish-Armenian relations to Turkey. However, what has been explained above demonstrate that the society of Armenia and the Armenian Diaspora make no attempt to engage in meaningful self-reflection concerning their faults. Under such circumstances, it does not seem possible for us to move towards reconciliation in Turkish-Armenian relations.

The comment made by Sevan Nişanyan on 25 August 2019 on his Facebook profile. Translation:

“1. Personal assassination is an effective and educational form of political struggle. It should be supported.

2. Those who risk their lives to enforce the justice that institutions fail to deliver are heroes. They should be glorified.

3. Sculpture in Armenia has regressed since the Soviet period. This should be rectified.”

The Soghomon Tehlirian statue in Armenia-Maralik during its unveiling

The Soghomon Tehlirian statue in Armenia-Maralik during its design stage

The photo of the Soghomon Tehlirian statue in Armenia-Maralik shared by Turkish media

[1] For example, please see: “‘Ermenistan'ın yaptığı bir skandaldır’,” CNN Türk, 27 Ağustos 2019, https://www.cnnturk.com/turkiye/ermenistanin-yaptigi-bir-skandaldir

[2] The first wave of terrorism took place between 1890-1905. The objective the terrorism perpetrated during this period was to prove that there were a Christian people who were struggling for freedom, even independence, in the Ottoman Empire. The third wave of terrorism took place between 1973-1986. The objective the terrorism perpetrated during this period was to draw the international public’s attention towards the genocide allegations.

[3] “Another statue is erected in the memory of Soghomon Tehlirian in Maralik,” Public TV Company of Armenia, April 23, 2015, https://news.1tv.am/en/2015/04/23/Soghomon-Tehlirian/13986

[4] “Another statue is erected in the memory of Soghomon Tehlirian in Maralik.”

[5] “Новые власти Армении не боятся: как поступили в Маралике с "Талаат-пашой," Sputnik, September 26, 2018, https://sptnkne.ws/jCuy ; “Куда исчезла голова Талаат-паши: история одного памятника Читать далее,” Sputnik, July 18, 2017, https://sptnkne.ws/vmyN

[6] Mkiıtar Nazaryan, “El pie de Tehlirian y la cabeza de Taleat,” Haydzayn.com, August 30, 2019, https://haydzayn.com/es/page/tehleryani-otqe-e-taleati-glouxe

[7] “Another statue is erected in the memory of Soghomon Tehlirian in Maralik.”

[8] Christopher Gunn, “Getting Away with Murder - Soghomon Tehlirian, ASALA, and the Justice Commandos, 1911-1984,” in War and Collapse – World War I and the Ottoman State, ed. M. Hakan Yavuz and Feroz Ahmad (Salt Lake City: The University of Utah Press, 2016), 902-903.

[9] Gunn, “Getting Away with Murder…,” 905-908.

[10] Gunn, “Getting Away with Murder…,” 909-910; Maxime Gauin, “Please Leave History To Historians - Article By Maxime Gauin, Daily Sabah, 21 May 2016,” Center for Eurasian Studies (AVİM), Blog No: 2016/19, May 25, 2016, https://avim.org.tr/Blog/PLEASE-LEAVE-HISTORY-TO-HISTORIANS-ARTICLE-BY-MAXIME-GAUIN-DAILY-SABAH-21-MAY-2016

[11] Gunn, “Getting Away with Murder…,” 909-910.

[12] Melek Sina Baydur, “Open Letter To The President Of Armenia - 27.05.2019,” Center for Eurasian Studies (AVİM), Blog No: 2019/33, May 28, 2019, https://avim.org.tr/Blog/OPEN-LETTER-TO-THE-PRESIDENT-OF-ARMENIA-27-05-2019

[13] Mehmet Oğuzhan Tulun, “A Nazi Who Is Armenia’s National Hero,” Center for Eurasian Studies (AVİM), Commentary No: 2016/34, June 16, 2016, https://avim.org.tr/en/Yorum/A-NAZI-WHO-IS-ARMENIA-S-NATIONAL-HERO

[14] Tulun, “A Nazi Who Is Armenia’s National Hero.”

[15] Mehmet Oğuzhan Tulun, “Armenia And The Veneration Of Terrorists,” Center for Eurasian Studies (AVİM), Commentary No: 2015/69, May 19, 2015, http://avim.org.tr/en/Yorum/ARMENIA-AND-THE-VENERATION-OF-TERRORISTS

[16] Oleg Yuryevich Kuznetsov, “The Ethno-Religious Origins of International Terrorism Perpetrated by Armenian Nationalists (Historical-Cultural Analysis),” Review of Armenian Studies, No. 35 (2017): 147-148; Aslan Yavuz Şir, “Bribe? A New Liability? Armenia’s New Iskander Missiles,” Center for Eurasian Studies (AVİM), Commentary No: 2016/55, October 25, 2016, http://avim.org.tr/en/Yorum/BRIBE-A-NEW-LIABILITY-ARMENIA-S-NEW-ISKANDER-MISSILES

[17] AVİM, “The Other Side Of The Coin-II: The Armenian Revolutionary Federation,” Center for Eurasian Studies (AVİM), Commentary No: 2019/27, March 28, 2019, https://avim.org.tr/en/Yorum/THE-OTHER-SIDE-OF-THE-COIN-II-THE-ARMENIAN-REVOLUTIONARY-FEDERATION

[18] AVİM, “The Other Side Of The Coin-II: The Armenian Revolutionary Federation.”

[19] For example, please see: Tülay Şubatlı, “Eşinin üzerine dışkı döktü!” (Translation: “He dumped feces on his wife!”) Vatan, 28 Haziran 2008, http://www.gazetevatan.com/esinin-uzerine-diski-doktu--186480-gundem/ ; “'Bu kadarına çüş' Sevan Nişanyan cinsel taciz için bunları yazdı!” (Translation: “‘This is too much’ Here’s what Sevan Nişanyan wrote about sexual harassment!”) Cumhuriyet, 31 Ocak 2019, http://www.cumhuriyet.com.tr/haber/turkiye/1225354/_Bu_kadarina_cus__Sevan_Nisanyan_cinsel_taciz_icin_bunlari_yazdi_.html

[20] Sevan Nişanyan, “[…] Buna karşılık suikast ve terörü yöntem olarak a priori reddeden, a priori güçlünün hukukuna ve zalimin kudretine boyun eğmiş demektir. […] Hayatı pahasına bireysel terör eylemine girişen kişinin büyüklüğünü ve trajedisini algılamaktan aciz insanları küçümsüyorum, evet. [...],” (Translation: “[…] Conversely, when someone a priori rejects assassination and terrorism, it means that s/he a priori submits to the law of the powerful and the might of the oppressor. […] Yes, I look down on people who are incapable of comprehending the greatness and tragedy of the person who risks his/her life to engage in personal terrorism […],”) Facebook comment, August 26, 2019 (12:55), https://www.facebook.com/nisanyan

© 2009-2025 Center for Eurasian Studies (AVİM) All Rights Reserved

No comments yet.

-

GENOCIDE ALLEGATIONS, PROPAGANDA MOVIES, AND A 90-MILLION-DOLLAR FIASCO

GENOCIDE ALLEGATIONS, PROPAGANDA MOVIES, AND A 90-MILLION-DOLLAR FIASCO

Mehmet Oğuzhan TULUN 14.07.2020 -

MEDDLING IN TURKISH-ARMENIAN RELATIONS: PROPOSED AMENDMENTS ON THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT RESOLUTION ON 2014 COMMISSION PROGRESS REPORT ON TURKEY

MEDDLING IN TURKISH-ARMENIAN RELATIONS: PROPOSED AMENDMENTS ON THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT RESOLUTION ON 2014 COMMISSION PROGRESS REPORT ON TURKEY

Mehmet Oğuzhan TULUN 03.05.2015 -

GENOCIDE AND GERMANY – II

GENOCIDE AND GERMANY – II

Mehmet Oğuzhan TULUN 18.10.2017 -

IS ECUMENISM BEING DISRUPTED IN THE CHRISTIAN WORLD?

IS ECUMENISM BEING DISRUPTED IN THE CHRISTIAN WORLD?

Mehmet Oğuzhan TULUN 24.09.2018 -

ARMENIA AND THE VENERATION OF TERRORISTS - II

ARMENIA AND THE VENERATION OF TERRORISTS - II

Mehmet Oğuzhan TULUN 16.09.2019

-

1934 PACT OF BALKAN ENTENTE: THE PRECURSOR OF BALKAN/SOUTHEAST EUROPE COOPERATION

1934 PACT OF BALKAN ENTENTE: THE PRECURSOR OF BALKAN/SOUTHEAST EUROPE COOPERATION

Teoman Ertuğrul TULUN 06.08.2020 -

CYCLE OF DESTABILIZATION AND RESTABILIZATION: IMPACTS ON BALKAN DEMOCRACIES

CYCLE OF DESTABILIZATION AND RESTABILIZATION: IMPACTS ON BALKAN DEMOCRACIES

Teoman Ertuğrul TULUN 20.12.2024 -

CHAPTER BY CHAPTER SYNOPSIS AND REVIEW OF TURKS AND ARMENIANS: NATIONALISM AND CONFLICT IN THE OTTOMAN EMPIRE BY JUSTIN MCCARTHY - 4

CHAPTER BY CHAPTER SYNOPSIS AND REVIEW OF TURKS AND ARMENIANS: NATIONALISM AND CONFLICT IN THE OTTOMAN EMPIRE BY JUSTIN MCCARTHY - 4

Ali Murat TAŞKENT 22.10.2015 -

EROSION IN ARMS CONTROL REGIMES CONTINUES

EROSION IN ARMS CONTROL REGIMES CONTINUES

Teoman Ertuğrul TULUN 12.10.2023 -

BREXIT: NEW PARADIGM SHIFT FOR GLOBALIZATION AND SIGNAL FOR NEW WORLD ORDER

BREXIT: NEW PARADIGM SHIFT FOR GLOBALIZATION AND SIGNAL FOR NEW WORLD ORDER

Teoman Ertuğrul TULUN 27.01.2017

-

25.01.2016

THE ARMENIAN QUESTION - BASIC KNOWLEDGE AND DOCUMENTATION -

12.06.2024

THE TRUTH WILL OUT -

27.03.2023

RADİKAL ERMENİ UNSURLARCA GERÇEKLEŞTİRİLEN MEZALİMLER VE VANDALİZM -

17.03.2023

PATRIOTISM PERVERTED -

23.02.2023

MEN ARE LIKE THAT -

03.02.2023

BAKÜ-TİFLİS-CEYHAN BORU HATTININ YAŞANAN TARİHİ -

16.12.2022

INTERNATIONAL SCHOLARS ON THE EVENTS OF 1915 -

07.12.2022

FAKE PHOTOS AND THE ARMENIAN PROPAGANDA -

07.12.2022

ERMENİ PROPAGANDASI VE SAHTE RESİMLER -

01.01.2022

A Letter From Japan - Strategically Mum: The Silence of the Armenians -

01.01.2022

Japonya'dan Bir Mektup - Stratejik Suskunluk: Ermenilerin Sessizliği -

03.06.2020

Anastas Mikoyan: Confessions of an Armenian Bolshevik -

08.04.2020

Sovyet Sonrası Ukrayna’da Devlet, Toplum ve Siyaset - Değişen Dinamikler, Dönüşen Kimlikler -

12.06.2018

Ermeni Sorunuyla İlgili İngiliz Belgeleri (1912-1923) - British Documents on Armenian Question (1912-1923) -

02.12.2016

Turkish-Russian Academics: A Historical Study on the Caucasus -

01.07.2016

Gürcistan'daki Müslüman Topluluklar: Azınlık Hakları, Kimlik, Siyaset -

10.03.2016

Armenian Diaspora: Diaspora, State and the Imagination of the Republic of Armenia -

24.01.2016

ERMENİ SORUNU - TEMEL BİLGİ VE BELGELER (2. BASKI)

-

AVİM Conference Hall 24.01.2023

CONFERENCE TITLED “HUNGARY’S PERSPECTIVES ON THE TURKIC WORLD"