In its classical age, the Ottoman State (Empire) granted autonomy to the minority religious communities, allowing them to regulate their own internal affairs. This system is commonly referred to as the Millet System. Under the Ottoman Millet System, which categorized various groups based on their religion, the Armenian Patriarch of Istanbul was given the authority to oversee the internal affairs of the Ottoman Armenian community. The Armenian Patriarchate held jurisdiction over community schools, churches, hospitals, and charitable institutions.

While this system functioned effectively and upheld the coexistence of various religious groups during the classical period, by the 19th century, it began to undermine the Ottoman State, particularly as nationalist and separatist ideologies started to infiltrate the education system. Community schools began to promote not only separatism but also animosity toward Turks and Muslims.

The Ottoman State, then referred to as “the sick man of Europe,” was too weak to manage its internal affairs effectively. As a result, the Great Powers frequently intervened to thwart Ottoman efforts at centralization and to impose tighter jurisdiction over Christian minorities.

By the late 19th and early 20th centuries, these schools began to be taken over by the revolutionary committees who had infiltrated these schools, using them to recruit young members and promote their radical ideas to a broader audience. In the Balkans, the newly established national states even dispatched secret agents posing as “teachers” to these institutions. In Eastern Anatolia, the Hunchaks and particularly the Dashnaks not only gained effective control of the Armenian community schools by recruiting teachers, but also appointed their influential members as school directors.

Added to these trends were the missionary schools. The missionaries not only exerted a religious influence on the Armenians through conversion but also had a significant political impact through the schools they established. While missionaries did not directly organize political movements, they played a crucial role in shaping the ethnic identity of the Christian inhabitants of the region. Toward the end of the 19th century, particularly after the Russo-Turkish War, missionaries increasingly assumed a political role among the Christian population, acting as spokespersons for Christian rights and vocal critics of the Ottoman government. In some instances, missionaries even incited violence; a foreign consul reported in 1888 that “a Protestant school in Harput [was] teaching students songs of a rather violent character that portrayed the Muslims as ‘religionless’ and ‘pitiless’.”

The national community schools were no different. The textbooks and other reading materials as well as songs and poems prepared for the pupils included a heavy dose of nationalism mixed with anti-Turkish and anti-Muslim rhetoric. These did not only promote nationalism and hatred of Turks and Muslims, but even advocated the use of mass violence against them and the overthrow of the Ottoman Government. In addition to the extreme nationalist indoctrination, the schools also trained young Armenian students in the manufacture and use of weapons and explosives. A case in point was the Sanasarian College in Erzurum.

According to a recent research by Cem Karakılıç, the Sanasarian College in Erzurum trained students in the manufacturing of weapons and explosives. Although the parents of the pupils did not want their children to be trained as blacksmiths and neither was there a demand for such professions, the school’s administrators insistently maintained instruments and training in this field. The reason was that these instruments and those students trained in this profession would be used in the manufacture of the weapons meant to be used by militant Armenian nationalist groups. Similarly, the young Armenian pupils of the school were taken out to open fields under the guise of “camping” and “hunting” and were trained in the use of rifles and guns.

Many of the infamous future Dashnaks had undergone thorough indoctrination and training in this school. Karekin Pastırmacıyan, a notorious terrorist who tried to blow up the Ottoman Bank with dynamites in 1895 and later during the First World War joined the invading Russian forces and massacred the Muslim population in Erzurum, was a graduate of the Sanasarian College.

As the example of the Sanasarian College in Erzurum shows, the Ottomans lost effective control and supervision of the minority schools, which worked to the detriment of the Ottoman State. The students were educated and trained in a way that alienated them from their government and from their Muslim neighbors. The result was the rise of a militant nationalism that was destructive for both the Armenians and the Muslims.

*Image: The building of the Erzurum Sanasarian College, which was renovated in subsequent years and now functions as the Erzurum Art and Sculpture Museum and Gallery Directorate.

© 2009-2025 Center for Eurasian Studies (AVİM) All Rights Reserved

THE PASSING AWAY OF THE ARMENIAN PATRIARCH OF ISTANBUL MESROP II AND THE NEW PATRIARCH ELECTION PROCESS

THE PASSING AWAY OF THE ARMENIAN PATRIARCH OF ISTANBUL MESROP II AND THE NEW PATRIARCH ELECTION PROCESS

RCEP AND ITS SIGNIFICANCE FOR THE SIGNATORY COUNTRIES FROM THE AUSTRALIAN PERSPECTIVE

GERMANY AND GENOCIDE: A MATTER OF DIPLOMATIC LEVERAGE

GERMANY AND GENOCIDE: A MATTER OF DIPLOMATIC LEVERAGE

OUTSIDE INTERVENTION TO THE ELECTION OF THE ARMENIAN PATRIARCH OF ISTANBUL CONTINUES

OUTSIDE INTERVENTION TO THE ELECTION OF THE ARMENIAN PATRIARCH OF ISTANBUL CONTINUES

NEW ARTICLE ON THE DASHNAK ERZURUM CONGRESS OF JULY 1914

NEW ARTICLE ON THE DASHNAK ERZURUM CONGRESS OF JULY 1914

10TH ANNIVERSARY OF TURKIC COUNCIL

10TH ANNIVERSARY OF TURKIC COUNCIL

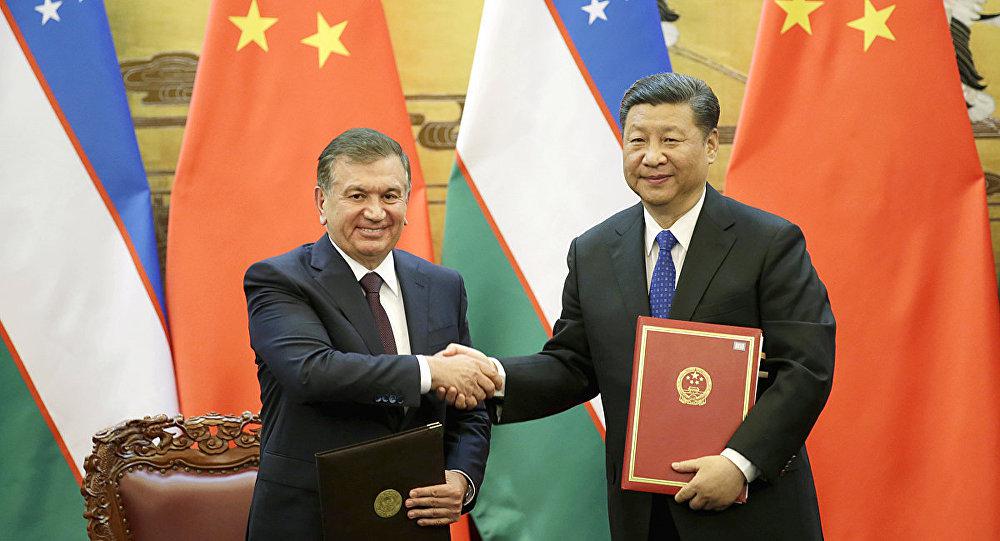

AN EVALUATION OF THE STRATEGIC AGREEMENT BETWEEN CHINA AND UZBEKISTAN

AN EVALUATION OF THE STRATEGIC AGREEMENT BETWEEN CHINA AND UZBEKISTAN

THE TENTH ANNIVERSARY OF HRANT DINK’S ASSASINATION

THE TENTH ANNIVERSARY OF HRANT DINK’S ASSASINATION

THE DIVERGENT AGENDAS OF THE ARMENIAN GOVERNMENT AND THE DIASPORA

THE DIVERGENT AGENDAS OF THE ARMENIAN GOVERNMENT AND THE DIASPORA