This is the English translation of a Turkish language article that was originally published by AVİM on 19 October 2023. The translation was made by AVİM Scholar in Residence İrem Akın.

Following the collapse of the Soviet Union and the emergence of independent states in Central Asia and the Caucasus, the international community encouraged these new states to adopt the secular "Turkish model". Moreover, the fact that these states had strong historical, cultural, ethnic, and linguistic ties with Türkiye provided the idea that Türkiye could be seen as an important stabilizing actor in the region. In the second half of the 1990s, following this positive period when Türkiye and the European Union had high expectations for the post-Soviet space, new challenges and conflicting interests in the region came to the fore.

Since the 2000s, Türkiye’s foreign policy towards Central Asia has been based not on high expectations but on a rational, institutionalization-based approach. The heads of state summits of the Cooperation Council of Turkic Speaking States, which were organized with the participation of Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Uzbekistan, Türkiye, and Turkmenistan since 1992, advanced the process of cooperation and interaction as a forum, albeit with interruptions. In line with the "new regionalism"[1] efforts, these summits were institutionalized as an international organization under the name of the Turkic Council with the Nakhchivan Treaty signed between Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Türkiye in 2009. The organization, which transcended regional borders by incorporating Hungary as an observer, evolved into the Organization of Turkic States in 2021 by attaining international standards. In this framework, it is being stated that Türkiye’s cooperation with the countries in the region has reached the level of a "regional community".[2] This stage entails "the deepening of social communication, the convergence of the values and actions of regional actors to a certain extent, and the transformation of the region into an active, institutionalized actor".[3]

The European Union, which prioritized expansion in Eastern Europe after the collapse of the Soviet Union, only started to develop stable relations with Central Asian countries in 1997. Security concerns arising from the Taliban's rise to power in Afghanistan had an impact on this. During this period, "Partnership and Cooperation Agreements" were negotiated bilaterally with Central Asian countries. The "Central Asia Strategy Paper 2002-2006" adopted in 2002 and the "Technical Assistance to the Members of the Commonwealth of Independent States" (TACIS) programs aim to contribute to the stability and security of the region and to support sustainable economic development and poverty reduction.

It was with the adoption of the "Strategy for a New Partnership with Central Asia" in 2007 that the European Union developed a full-fledged policy towards Central Asia. The development of this policy was the result of the EU’s growing strategic interest in the region and the fact that Germany, which assumed the presidency of the Union in 2007, identified Central Asia as one of its policy priorities. In particular, the difficulties experienced with Russia's energy supply to European countries have come to the forefront as one of the factors shaping the EU’s policies in this region. In this framework, Central Asian countries have been identified as one of the priority regions for the EU to cooperate with in line to provide wider access to energy resources worldwide.

In 2014, the EU's increased funding for Central Asia and its attempt to formulate another strategy in 2019 were in response to the Russia-Ukraine conflict and later China's growing influence in the region through the Belt and Road Initiative. Brussels proposed the Europe-Asia Connectivity Strategy in 2018 and a second “Central Asia Strategy" in 2019, 12 years after the first one. According to this strategy, the EU would focus on promoting resilience, prosperity, and regional cooperation in the region. Like the 2007 strategy, the 2019 strategy includes many unrealizable areas for cooperation, leaving the impression that its implementation will be weak.[4]

The EU's Central Asia policy suffers from a reactive process of development and a failure resulting from the EU's tendency to make unrealistic commitments. The EU's energy crisis in the aftermath of the 2022 Russia-Ukraine war highlighted the consequences of the lack of progress in relations with Central Asia. Türkiye’s important initiatives in the region were ignored by the EU, resulting in a missed opportunity that could have been a win-win for all parties in Central Asia. Unfortunately, the EU failed to learn the necessary lessons because of its narrow and prejudiced approach, and even today, unfortunate statements have been made by the Head of the Central Asia Department of the European Union External Relations Service, warning Central Asian countries that they would face "negative consequences" if they "approve the accession of the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus as an observer to the Organization of Turkic States."[5]

These developments show that the EU is unable to go beyond the constraints it imposes on itself. Central Asia has significant potentials waiting to be realized. In an environment where other regional and global actors are cooperating on various platforms in Central Asia, the EU needs to recognize the need for cooperation with Türkiye in Central Asia.

[2] Pelin Musabay Baki, La Coopération Entre Les Pays Turcophones et Le Nouveau Régionalisme, Galatasaray Üniversitesi Doktora Tezi, 2020, p. 488.

[3] Björn Hettne, and Fredrik Söderbaum, "Theorising the rise of regionness." New political economy 5.3 (2000): 457-472.

[4] Fabienne Bossuyt, “The European Union’s New Strategy for Central Asia: A Game Changer or More of the Same?”, Avrasya Dünyası / Eurasian World 6 (2020), p. 40.

© 2009-2025 Center for Eurasian Studies (AVİM) All Rights Reserved

24TH MEETING OF THE COUNCIL OF HEADS OF STATE OF THE SHANGHAI COOPERATION ORGANIZATION

24TH MEETING OF THE COUNCIL OF HEADS OF STATE OF THE SHANGHAI COOPERATION ORGANIZATION

INDIA–MIDDLE EAST–EUROPE ECONOMIC CORRIDOR (IMEC)

INDIA–MIDDLE EAST–EUROPE ECONOMIC CORRIDOR (IMEC)

EURASIA REGIONAL TRANSPORT CORRIDORS

EURASIA REGIONAL TRANSPORT CORRIDORS

FACTORIES USING FORCED LABOUR OF THE UYGHURS PROVIDE SUPPLIES FOR 83 WELL-KNOWN BRANDS

FACTORIES USING FORCED LABOUR OF THE UYGHURS PROVIDE SUPPLIES FOR 83 WELL-KNOWN BRANDS

HOW HAVE THE SANCTIONS IMPOSED ON RUSSIA AFFECTED CHINA?

HOW HAVE THE SANCTIONS IMPOSED ON RUSSIA AFFECTED CHINA?

ACADEMIC DEBATE V. CHEAP SLANDER

ACADEMIC DEBATE V. CHEAP SLANDER

A HYPOCRITICAL CALL FOR INTER-RELIGIOUS DIALOGUE

A HYPOCRITICAL CALL FOR INTER-RELIGIOUS DIALOGUE

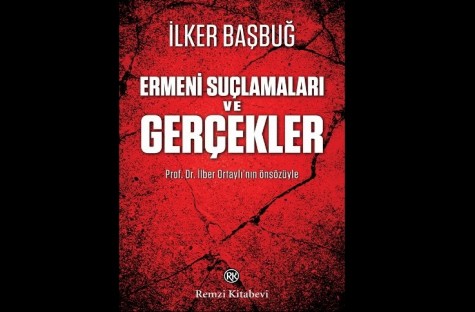

BOOK REVIEW: ARMENIAN ALLEGATIONS AND FACTS (ERMENİ SUÇLAMALARI VE GERÇEKLER)

BOOK REVIEW: ARMENIAN ALLEGATIONS AND FACTS (ERMENİ SUÇLAMALARI VE GERÇEKLER)