In the last couple weeks a high profile Turkish movie called 'Ayla: the Daughter of War' came out and was nominated for the international Academy Awards (The Oscars). The movie tells the story of a Korean orphan adopted by a Turkish soldier during the Korean War. Korea and Turkey, two countries situated at the eastern and western extremities of the Asian continent have had limited historical contact in the past. Perhaps, the success of this movie could be seen as a sign that this will soon change.

The late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries have been devastating for Korea; the declining Chinese Empire and the rising Japanese and Russian Empires clashed for dominating the extremely strategic peninsula. This process resulted in the Japanese annexation in 1910 that deprived Korea of its sovereignty which would only be regained after the Second World War. However, as the Cold War started, Korea became a geopolitical fault line between the United States, China and the Soviet Union. As a result of this, the country was dragged into one of the bloodiest conflicts since the end of the Second World War. The Korean War is still ongoing in many ways, as the border that was drawn at the end of the conflict is now a demilitarised zone that separates the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea and the Republic of Korea.

Korea has therefore often been seen as a victim of historical forces, a country situated in a hotly contested fault line. Today, both Koreas developed their ways to no longer be the victim of these larger forces. North Korea relies on its weapons of mass destruction, hoping that they would deter any aggression against the country’s government. South Korea is also a fairly militarised country even though not even near the extent that the North is. South Korea’s key asset is not its military: the country went through an extremely rapid and successful modernisation process. Having had a level of income equivalent of Subsaharan African countries as late as 1960, South Korea now has the 11th largest GDP in the world with a quality of life that rivals that of Western Europe. This extraordinary increase in wealth was obtained with a policy of Export Led Industrialisation. Taking advantage of its access to sea lanes, the country initially traded mostly with Japan and the United States. Gradually, with its opening to the world economy, China became its main trade partner. The development of global trade favoured South Korean companies which, through efficient public policies, became extremely competitive in the international market. As a result, South Korea’s economy relied on trade to a great extent. Even today, 45% of South Korean GDP is composed of exports (in comparison, this rate is 22% for China). As the 5th largest exporter and 9th largest importer in the world, it is crucial for South Korea to maintain its access to world trade routes it depends on.

Therefore, if the Pacific Rim where these sea routes are concentrated are destabilised, South Korea would suffer greatly. Until the current rivalry between China and the United States, the security of Pacific sea lanes was taken as granted as the American Navy exercised supreme command of the region. However, this situation is swiftly evolving as the new Chinese superpower emerges and the United States aims to deter it with the help of its regional allies. The South China Sea disputes are just one chapter in an escalation of tensions that could happen in the near future. As the 2014 US navy report entitled 'Deterring the Dragon' shows, certain elements within the US military advocate radical measures such as practically blockading the Chinese coast.

Among other reasons, facing the extreme danger of this scenario, the Chinese government introduced the ambitious One Belt One Road project that aims to revitalise the ancient Silk Road trade network which connected the Eurasian landmass through land. In fact, South Korea’s 'Eurasia Initiative' is partly based on a similar logic. If the Silk Road network successfully comes to existence again, South Korea could benefit from an additional trade route. Among other things, the country could diversify its energy suppliers by establishing closer ties with Central Asian countries; a diplomatic goal that has been articulated in the 2013 Samarkand summit by the South Korean president.

In fact, as these advances for facilitating Eurasian trade are made, one should increasingly look at the supercontinent as a cohesive unit. Turkey and South Korea would be much closer to each other within such a cohesive Eurasia.

However, there is still a major issue standing in the way of this process for Korea: the DPRK regime. As China sees the fall of the regime and the unification of Korea as a geopolitical threat, it did not include South Korea in its One Belt One Road network plans. In fact, an increase in trade involving North Korea would lead to an opening of the DPKR regime to globalisation that could seriously undermine the stability of the current government. But as long as North Korea is not involved in this emerging Eurasian trade network, South Korea will be cut off from the land-based components of it. Future geopolitical developments will show whether this critical issue can be overcome.

Bibliography:

HWANG Balbina; What South Korea thinks of China’s Belt and Road; the Diplomat; 14th January 2017.

ROBERTSON Jefrey; Seoul’s Middle Power Turn in Samarkand; the Diplomat; 8h of July 2014.

TAEHWAN Kim; Beyond Geopolitics: South Korea’s Eurasia Initiative as a New Nordpolitik; 16th February 2015.

© 2009-2025 Center for Eurasian Studies (AVİM) All Rights Reserved

WHAT FUTURE FOR ARMENIAN-RUSSIAN RELATIONS?

WHAT FUTURE FOR ARMENIAN-RUSSIAN RELATIONS?

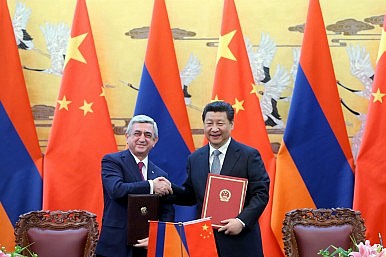

CHINA’S GROWING PRESENCE IN THE CAUCASUS

CHINA’S GROWING PRESENCE IN THE CAUCASUS

TURKEY AND KOREA DRAWING CLOSER

TURKEY AND KOREA DRAWING CLOSER

THE 2020 PRESIDENTIAL ELECTIONS IN MOLDOVA: A NEW POLITICAL CONTEXT IN THE POST-SOVIET SPACE?

THE 2020 PRESIDENTIAL ELECTIONS IN MOLDOVA: A NEW POLITICAL CONTEXT IN THE POST-SOVIET SPACE?

TURKEY AND KOREA DRAWING CLOSER

TURKEY AND KOREA DRAWING CLOSER

AUSTRIA AND LUXEMBURG: EFFORTS TO REPAIR RELATIONS

AVIM’S CONFERENCE ENTITLED SECURITY AND STABILITY CONCERNS IN SOUTH CAUCASUS

AVIM’S CONFERENCE ENTITLED SECURITY AND STABILITY CONCERNS IN SOUTH CAUCASUS

NAGORNO-KARABAKH AND CRIMEA: A COMPARISON OF DOUBLE STANDARDS

NAGORNO-KARABAKH AND CRIMEA: A COMPARISON OF DOUBLE STANDARDS