Armenia and European Union (EU) recently revised their terms of engagement and initiated a “Comprehensive and Enhanced Partnership Agreement” (CEPA) within the framework of EU’s Eastern Partnership program. CEPA was initiated on 21st of March, 2017 to replace the previous initiated but not signed Association Agreement as Armenia decided to join Russia’s Eurasian Union with an unexpected U-turn in 2013 in the aftermath of Sargasyan’s visit to Moscow.

EU’s relations with Armenia are based on EU-Armenia Partnership and Cooperation Agreement which was signed in 1999. Currently, Armenia and EU are engaging under the umbrella of EU’s Eastern Partnership (EaP) program which was initiated in 2009 with 5-more post-Soviet countries. However, two out of six countries decided to join Russia’s Eurasian Union and suspended the integration process with EU since the Association Agreement is not compatible with Eurasian Union’s regulations. The official re-launch of the negotiations with Armenia took place on 7th of December, 2015 and it was completed on 27th of February 2017.[1]

Considering the geopolitical positions, security concerns, different social dynamics and political experiences, it is possible to say that foreign policy orientations and domestic trends in the six EaP countries are different from each other. On the one hand, Ukraine and Georgia pursued pro-Western policies particularly following their troubled times with Russia, on the other hand, Armenia and Belarus decided to join Eurasian Union because of their heavy reliance on Russia. Moldova and Azerbaijan preferred relatively balanced policies. Therefore, instead of covering all of them under one specific program, adaptation of focused guidelines for each country on their own merits might have better outcomes and this is what EU has been working on with Armenia. In 2015, EU underlined the need for a new policy to engage with Armenia in the field of trade in the progress report by saying “…EU-Armenia trade relations will need to be redefined following Armenia’s accession to the Eurasian Customs Union.”[2] Although, Russia’s presence is very strong in Armenia, EU and Armenia are important trade partners.

However, EU-Armenia relations have a limited scope, because Russia has no intention to give up on its “near abroad” and the tensions in the South Caucasus has been increasing in the last couple of years. Armenia’s reliance on Russia in the fields of energy, security and economy is among the biggest obstacles for Armenia’s integration with the European Union.

Firstly, Russia serves as the security guarantor of Armenia and is gradually increasing its military presence in the South Caucasus. In 2010, Armenia signed an agreement with Russia to extend lease of Russia’s 102th military base in Gyumri until 2044. Originally it was supposed to expire in 2020. Considering the fact that the second biggest city Gyumri is only 20 km away from the borders of Turkey, a NATO member since 1952 and a country hosting İncirlik base in its territories, it explains Russia’s motivations behind its interest in Armenia’s security. Armenia’s motivation behind delegating its own national security to Russia is the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict. The frozen conflict worsened in 2016 and turned into a 4-day-war. The Nagorno-Karabakh conflict has a negative impact over regional stability and integration in the South Caucasus. Also, revisionist policies of the Armenian government leads the country to a more isolated position, hence, Armenia’s dependency on Russia is increasing.

With that perspective, Armenia joined the Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO) in 2002[3]. Nevertheless, Armenia cooperates with North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) in the framework of Peace for Partnership (PfP) programmes, conducting high level talks with NATO officials, and contributes to NATO’s missions; KFOR (NATO Kosovo Force) since 2004 and to International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) since 2009. CSTO membership and NATO partnership appears to be constructed as technically not contradicting. Hence the Euro-Atlantic bloc did not react to increasing Russian military presence in its south-eastern border: Armenia. For instance, Armenian news report that an advanced Russian military capability, Iskander-M (Ballistic Missile Systems, SRBMS – also known as SS-26 Stone) was deployed in Armenia in 2013.[4] From NATO-Russia relations perspective, this can be considered as a major move considering the current security challenges in the wider Black Sea region. The blurry relations of Armenia with the West, EU and NATO, has brought many questions along. It is still unclear why Euro-Atlantic bloc has been pursuing closer relations with Armenian government than other CTSO members, despite its decisions that enabled Russia to establish a strong ground for Russian military capabilities. Considering Armenia’s geo-political position, we can argue that Armenia’s decisions related to Russia will and does have an impact on regional security in the wider Black Sea, beyond bilateral relations.

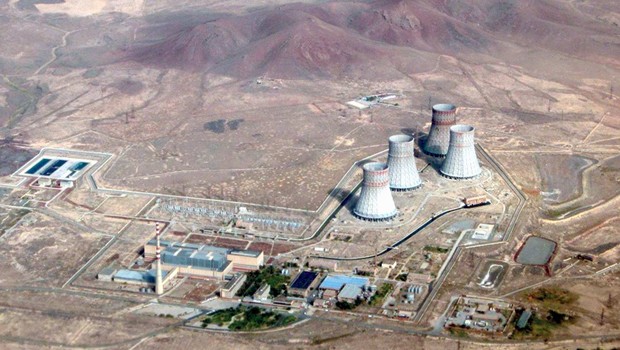

Secondly, Armenia has no energy resources, except the Metsamor Nuclear Power Plant which is highly risky considering its conditions and location. Russia took the responsibility of the Soviet-technology power plant’s technical works to keep it operating until 2026 with an agreement signed in 2015. The European Union repeatedly expressed its concerns about Metsamor and urged authorities to close the Nuclear Power Plant as promptly as possible. However, it is still operating at the expanse of the security of the entire South Caucasus including Turkey. Armenia sold the remaining %20 stake of ArmRosgazprom to Russia’s Gazprom in 2014 and now ArmRosgazprom changed its name to Gazprom Armenia. Consequently, natural gas flows from Iran to Armenia or Georgia also controlled by a Russian company, not Armenia. Electricity is also among the sectors which are totally controlled by Russian companies; Electric Networks of Armenia (ENA) is owned by Inter RAO UES. Russia managed to keep Armenia’s energy market and prices under its full control, leaving Armenia no option to diversify its energy resources. To realize the danger in Russia’s full control over the energy markets and prices, it is important to recall protests that took place in 2016 in reaction to increasing electricity prices in Armenia.

In addition, Armenian citizens are traveling to Russia to find jobs, and remittances of Armenian labor migrants in Russia are an important income channel for Armenia. According to the World Bank, unemployment rate in Armenia was %17.1 in 2014 and the number of Armenian labor migrants has been increasing. For example, according to Russia’s Federal Migration Service, %20 more Armenians went to Russia in 2013 (roughly 670,000) compared to 2012, and the National Statistical Service of Armenia states that %90 of the people who travel to Russia is looking for job opportunities.[5] A report notes that: “According to the Central Bank of Armenia, remittances from Russia account for 84.6 percent of the overall $942 million transferred to Armenia during the first two quarters of 2013, the latest period for which data is available. The amount marks a 12-percent increase from the same period in 2012.”[6] Yet, due to current economic crisis in Russia, remittances fell %36.1 in 2015 compared to 2014 and equaled approximately to 915.9 million US Dollars.[7]

Thereby, the only areas of cooperation for Armenia and EU are politics and civil society. However, Armenia’s decision to join Eurasian Union cannot have a positive impact on its democratic progress since Eurasian Union does not have such an agenda. Being aware of this gap, EU aims to strengthen cooperation with Armenia on the political and civil spheres besides energy and environment. The joint press release published by the Armenia’s Foreign Ministry and EU says: “Strong commitments to democracy, human rights, and the rule of law, underpin the new agreement and Armenia-EU future cooperation…The Comprehensive and Enhanced Partnership Agreement (CEPA) will also create the framework for stronger cooperation in sectors such as energy, transport and the environment, for new opportunities in trade and investments, and for increased mobility for the benefit of the citizens.”[8] On the one hand, cooperation between Russia and Armenia is strengthening; on the other hand, EU is seeking a way to maintain its relations with Armenia. Time will show whether the new agreement will succeed or not, yet abovementioned challenges for further cooperation still remain.

In addition, according to Armenian civil society representatives, there is a lack of communication between the public and authorities. For example, Boris Navasardian, Eastern Partnership Civil Society Forum country facilitator for Armenia, said: “The lack of knowledge among the population about the details of the agreement, especially in light of the active propaganda against the deepening of Armenia’s cooperation with the EU and against the European values in general, present serious risks for the future implementation of the Agreement” in a statement EaP CSF issued on 22nd of March, 2017.[9] His statement gives an idea about the complexity of the issues and brings questions to mind about whether CEPA was an outcome of a comprehensive and inclusive process or not.

It is important to keep countries that are willing to integrate in EU’s market and adopt democratic values on track and support their works to promote security and increase welfare in the region. Yet, we should question whether Armenia is one of them or not. Despite the unclear environment and mixed signals, European Union adopted an unbalanced approach towards South Caucasus in recent years. Although there are similar problems in the post-Soviet space concerning democracy, security and economy, not all of them benefit from EU’s favoring attitudes. For example, a pro-western country in the South Caucasus, Georgia, will be able to enjoy visa-free entrance to European Union which will promote mobility. Armenia is also expecting to launch visa liberalization talks with EU. Yet there is no intention to adopt a similar policy towards Azerbaijan despite EU’s good relations with the country. It is possible to observe the same contradictions in the Balkans; particularly in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Bosnia has been trying to develop its relations with the EU but has not received any status, while Croatia has rapidly become a member of the EU and Serbia a candidate.

In conclusion, there is an obvious strategic move and Armenia is playing a two-sided diplomacy to gain as much as it can from both sides. The main discourse of the Armenian government to justify its policies is the current conflicts in Nagorno-Karabakh, even though Armenian military and authorities refuse to end the aggression to establish a stable ground for peace in the region. Armenia prefers neither Russia nor the Euro-Atlantic bloc and it is striking that none of the parties openly express their displeasure even though there is a security dimension involved. Also, neither Europe nor Russia is willing to leave their area of influence to one another and Armenia has been the ground for both actors to compete on.

Photo: European Council

[1] European Union External Action, EU-Armenia relations, 27 February 2017, https://eeas.europa.eu/headquarters/headquarters-homepage_en/4080/EU-Armenia%20relations

[2] European Commission, Implementation of the European Neighbourhood Policy in Armenia Progress in 2014 and recommendations for actions,25 March 2015, http://eeas.europa.eu/archives/docs/enp/pdf/2015/armenia-enp-report-2015_en.pdf

[3] An intergovernmental organization on security created by Russia

[4] Asbarez, Russia Stations Advanced Missiles in Armenia, 3 June 2013, http://asbarez.com/110400/russia-stations-advanced-missiles-in-armenia/

[5] Marianna Grigoryan, Armenia: Russia Puts Squeeze on Migrant Workers, Eurasianet, 24 february 2014, http://www.eurasianet.org/node/68078

[6] Marianna Grigoryan, Armenia: Russia Puts Squeeze on Migrant Workers, Eurasianet, 24 february 2014, http://www.eurasianet.org/node/68078

[7] PanArmenia, Private remittances from Russia to Armenia drop by 30.1% to $915.9 mln, 1 February 2016, http://www.panarmenian.net/eng/news/205052/

[8] European Union External Action, Joint Press Release by the European Union and Republic of Armenia on the initialling of the EU-Armenia Comprehensive and Enhanced Partnership Agreement, 21 March 2017, https://eeas.europa.eu/headquarters/headquarters-homepage/23120/joint-press-release-european-union-and-republic-armenia-initialling-eu-armenia-comprehensive_en

[9]Eastern Partnership Civil Society Forum, Statement on the EU-Armenia Comprehensive and Enhanced Partnership Agreement, 30 March 2017, http://eap-csf.eu/index.php/2017/03/30/statement-by-the-steering-committee-of-the-eastern-partnership-civil-society-forum-on-the-eu-armenia-comprehensive-and-enhanced-partnership-agreement/

© 2009-2025 Center for Eurasian Studies (AVİM) All Rights Reserved

No comments yet.

-

25TH ANNIVERSARY SUMMIT OF THE BLACK SEA ECONOMIC COOPERATION

25TH ANNIVERSARY SUMMIT OF THE BLACK SEA ECONOMIC COOPERATION

Özge Nur ÖĞÜTCÜ 31.05.2017 -

A NEW PAGE FOR ARMENIA-EU RELATIONS?

A NEW PAGE FOR ARMENIA-EU RELATIONS?

Özge Nur ÖĞÜTCÜ 06.04.2017 -

METSAMOR AND REGIONAL NUCLEAR-SECURITY IN THE SOUTH CAUCASUS

METSAMOR AND REGIONAL NUCLEAR-SECURITY IN THE SOUTH CAUCASUS

Özge Nur ÖĞÜTCÜ 14.06.2016 -

RUSSIA AND THE WEST: ASSESMENT OF THE CURRENT DEVELOPMENTS

RUSSIA AND THE WEST: ASSESMENT OF THE CURRENT DEVELOPMENTS

Özge Nur ÖĞÜTCÜ 14.10.2014 -

BUSY FEBRUARY AGENDA: UKRAINE ON THE FOCUS

BUSY FEBRUARY AGENDA: UKRAINE ON THE FOCUS

Özge Nur ÖĞÜTCÜ 22.02.2015

-

INTRODUCING RELIGION INTO A LEGAL AND HISTORICAL DISPUTE

INTRODUCING RELIGION INTO A LEGAL AND HISTORICAL DISPUTE

Mehmet Oğuzhan TULUN 12.04.2015 -

THE INAUGURATION SPEECH OF THE NEWLY ELECTED ARMENIAN PRESIDENT ARMEN SARKISSIAN: MORE OF THE SAME IDEOLOGICAL OUTLOOK

THE INAUGURATION SPEECH OF THE NEWLY ELECTED ARMENIAN PRESIDENT ARMEN SARKISSIAN: MORE OF THE SAME IDEOLOGICAL OUTLOOK

Turgut Kerem TUNCEL 17.04.2018 -

FRANCE IS BLOWING HOT AND COLD

Ömer Engin LÜTEM 20.11.2011 -

THE ARMENIAN LAW AND THE FRENCH CONSTITUTIONAL COURT

Ömer Engin LÜTEM 01.02.2012 -

IRAN, KAZAKHSTAN, TURKMENISTAN AND CHINA: REGIONAL CONNECTIVITY

IRAN, KAZAKHSTAN, TURKMENISTAN AND CHINA: REGIONAL CONNECTIVITY

Özge Nur ÖĞÜTCÜ 09.05.2016

-

25.01.2016

THE ARMENIAN QUESTION - BASIC KNOWLEDGE AND DOCUMENTATION -

12.06.2024

THE TRUTH WILL OUT -

27.03.2023

RADİKAL ERMENİ UNSURLARCA GERÇEKLEŞTİRİLEN MEZALİMLER VE VANDALİZM -

17.03.2023

PATRIOTISM PERVERTED -

23.02.2023

MEN ARE LIKE THAT -

03.02.2023

BAKÜ-TİFLİS-CEYHAN BORU HATTININ YAŞANAN TARİHİ -

16.12.2022

INTERNATIONAL SCHOLARS ON THE EVENTS OF 1915 -

07.12.2022

FAKE PHOTOS AND THE ARMENIAN PROPAGANDA -

07.12.2022

ERMENİ PROPAGANDASI VE SAHTE RESİMLER -

01.01.2022

A Letter From Japan - Strategically Mum: The Silence of the Armenians -

01.01.2022

Japonya'dan Bir Mektup - Stratejik Suskunluk: Ermenilerin Sessizliği -

03.06.2020

Anastas Mikoyan: Confessions of an Armenian Bolshevik -

08.04.2020

Sovyet Sonrası Ukrayna’da Devlet, Toplum ve Siyaset - Değişen Dinamikler, Dönüşen Kimlikler -

12.06.2018

Ermeni Sorunuyla İlgili İngiliz Belgeleri (1912-1923) - British Documents on Armenian Question (1912-1923) -

02.12.2016

Turkish-Russian Academics: A Historical Study on the Caucasus -

01.07.2016

Gürcistan'daki Müslüman Topluluklar: Azınlık Hakları, Kimlik, Siyaset -

10.03.2016

Armenian Diaspora: Diaspora, State and the Imagination of the Republic of Armenia -

24.01.2016

ERMENİ SORUNU - TEMEL BİLGİ VE BELGELER (2. BASKI)

-

AVİM Conference Hall 24.01.2023

CONFERENCE TITLED “HUNGARY’S PERSPECTIVES ON THE TURKIC WORLD"