Chapter 5: Armenians and the Ottoman Revolution

McCarthy’s narration of this chapter begins with an overview of Abdülhamit II’s reign and its consequences. The repressive reign of sultan Abdülhamit II led to the formation of revolutionary groups amongst Ottoman military officers and intellectuals who came to believe that radical changes were needed to prevent the disintegration of the Ottoman Empire. Some believed in centralization of power with a strong government, a unified state, and an Ottoman nationalism that moved passed ethnic identities. Others believed in a system of autonomous national groups which would nevertheless work together for the good of the empire.

These differing revolutionary plans were cut short by the revolt of the Third Army in 1908, which brought a different kind of Ottoman Revolution that placed the Committee of Union and Progress (CUP) to power within the empire. Out of practical considerations, CUP chose to collaborate with the Dashnaks, seeing them as a key to appeasing Western powers. The Dashnaks became an integral part of the political alliances that kept CUP in power, became the main representative force of Ottoman Armenians, and used their position to bring many of their members (who actively worked to undermine the empire) into positions within the empire’s administrative and political system. However, despite their proclaimed loyalty to the empire, the CUP always suspected that the Dashnaks were in fact vying for secession. When, in the subsequent years, the CUP managed to firmly establish itself in power and when it realized that there was simply no way to appease the Western powers, relations between CUP and the Dashnaks began to deteriorate.

The incident in Adana in 1909 only served to mark up the tension between the Armenian revolutionaries such as the Dashnaks and the empire. Armenian revolutionaries were encouraging local Armenians in this region to arm themselves. As put forth by the British consul in Adana, the swagger with which the local Armenians carried their guns and their verbal remarks began to provoke the local Muslims. Tensions between both sides eventually turned a minor altercation into a major communal fight. Although the local Armenians had the guns, the local Muslims had the numbers. Roughly 5000 Armenians and 1000 Muslims perished in the violence and excessive behavior that ensued. The Ottoman government took action against the perpetrators of violence, albeit in an ineffective way, for example by executing some of the culprit Muslims and Armenians. As McCarthy puts it; “No one planned the events in Adana, neither the Armenians nor the Turks. The deaths resulted from a long-simmering distrust between Muslims and Armenians.”

The fight over property rights in eastern Anatolia further damaged the relations between Ottoman Armenians and the empire. The Ottoman government exercised weak control over the Kurdish tribes who operated in eastern Anatolia. These tribes vied for power amongst each other, extracting protection money from Muslim and Armenian farmers alike, and paying few taxes to the government. Meanwhile, wealthy Armenian money landers also preyed on the population by lending money and seizing property when debts were not paid. As such, Kurdish overlords and Armenian lenders turned local farmers into little more than serfs. The Dashnaks wanted reforms to improve Armenian farmers’ situation. However, the Ottoman Empire lacked the manpower to truly bring the Kurdish tribes and carry out reforms for the good of both Muslim and Armenian farmers, and furthermore did not wish to alienate the Kurdish tribes too much and risk losing their military support against the Russian Empire. Some Kurdish tribes actually collaborated with the Russians when it suited their interests. As such, the Ottoman government adopted a delaying tactic against all sides, which pleased no one, and increased the suspicion held both by Armenian revolutionaries and Kurdish tribes. The Dashnaks wanted the “feudalist” Kurdish tribes to be punished, something the government was incapable of doing. Meanwhile, the Kurdish tribes saw the government as an “enemy of traditional status and privileges” of the tribes. As such, the Ottoman Empire was caught in the middle of two conflicting sides, incapable to finding an effective solution.

The Dashnaks gained great legitimacy and influence from being a part of the CUP government. They used pressure and punishment to silence or remove any Armenian who did not agree with their work and methods. This included forcing the removal of the Armenian Patriarch of Istanbul. Knowing that the CUP regime’s reluctance to put a stop to their machinations to avoid Western interference, the Dashnaks went about stockpiling weapons and recruiting revolutionaries. They intimidated local Armenians into buying the weapons they were selling, making a huge profit out of them. They also drew up elaborate plans for what McCarthy calls “partisan warfare”, meaning a revolutionary and secessionist struggle that was to be waged against the empire and the Muslim population. These plans were distributed in communities where Armenians lived, who were expected to carry out the orders given to them. As McCarthy points out, the actions of Armenian revolutionaries such as the Dashnaks was very alarming for the Ottoman Empire. The Armenian revolutionaries’ involvement in the creation of the two “inspectorates” (easily exploitable special administrative zones established with the pressure of Western powers and Russia) in the eastern section of the empire was the final nail in the coffin for relations between the Ottoman government and the Armenian revolutionaries. The Ottoman government came to see the Armenian revolutionaries as untrustworthy groups that posed a danger no different than that of the one posed by the British, French or Russians.

McCarthy’s narration of these events serve to highlight the following fact to the reader: the latter half of the 19th century and the 20th century presented a number of conundrums for the Ottoman Empire. Both the Western powers and the people of the Ottoman Empire were well aware that the empire was in decline and that reform was need to resuscitate it. However, the Ottoman Empire lacked the resources and unity needed to carry out such reforms.

As McCarthy explains, the empire needed the cooperation of both Ottoman Armenians and Kurdish tribes to make reforms easier to carry out, but both groups actually worsened the situation with their behavior. In the end, the weakening Ottoman Empire became caught in the middle of the power struggle of Western powers and Russia, and the machinations of both Kurdish tribes and Armenian revolutionaries. It simply lacked the capacity to carry out changes that would have help put a stop to its disintegration.

FRANCE 24-THE OBSERVERS PROGRAMME AND FAKE NEWS

FRANCE 24-THE OBSERVERS PROGRAMME AND FAKE NEWS

SOME CRITICISMS REGARDING PROF. DR. ERIK-JAN ZÜRCHER’S CENTENNIAL STATEMENT - II

SOME CRITICISMS REGARDING PROF. DR. ERIK-JAN ZÜRCHER’S CENTENNIAL STATEMENT - II

OPPOSITION AGAINST THE TURKEY-ARMENIA NORMALIZATION PROCESS THROUGH THE USE OF CARTOONS

OPPOSITION AGAINST THE TURKEY-ARMENIA NORMALIZATION PROCESS THROUGH THE USE OF CARTOONS

OUTSIDE INTERVENTION TO THE ELECTION OF THE ARMENIAN PATRIARCH OF ISTANBUL

OUTSIDE INTERVENTION TO THE ELECTION OF THE ARMENIAN PATRIARCH OF ISTANBUL

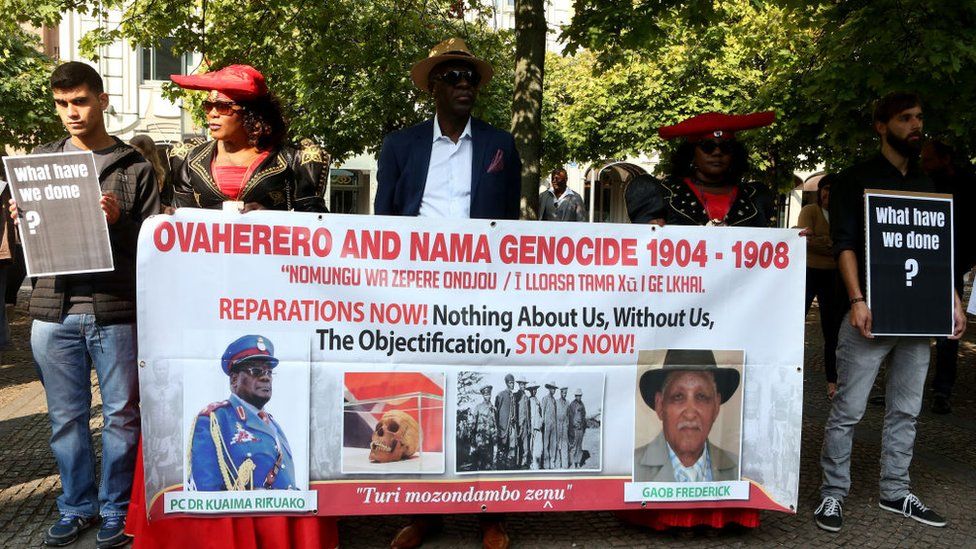

GENOCIDE AND GERMANY - III

GENOCIDE AND GERMANY - III

NİKOL PASHİNYAN’S SPEECH IN THE WORLD WAR I ARMISTICE EVENT REVEALS HIS INTENTIONS REGARDING 1915 EVENTS

NİKOL PASHİNYAN’S SPEECH IN THE WORLD WAR I ARMISTICE EVENT REVEALS HIS INTENTIONS REGARDING 1915 EVENTS

MACRON’S PROPOSAL OF CREATING EUROPEAN POLITICAL COMMUNITY AND NATO'S GUARDIAN ANGEL WINGS

MACRON’S PROPOSAL OF CREATING EUROPEAN POLITICAL COMMUNITY AND NATO'S GUARDIAN ANGEL WINGS

SOME CRITICISMS REGARDING PROF. DR. ERIK-JAN ZÜRCHER’S CENTENNIAL STATEMENT - II

SOME CRITICISMS REGARDING PROF. DR. ERIK-JAN ZÜRCHER’S CENTENNIAL STATEMENT - II

TAIWAN’S SOVEREIGNTY AND “ONE CHINA” DILEMMA

TAIWAN’S SOVEREIGNTY AND “ONE CHINA” DILEMMA

BETWEEN SYMBOLIC VICTORY AND COLD REALITY: THE DIVEST TURKEY CAMPAIGN

BETWEEN SYMBOLIC VICTORY AND COLD REALITY: THE DIVEST TURKEY CAMPAIGN