Ruben Safrastyan, an Armenian historian as well as a member of the Armenian National Academy of Sciences, has published an article titled “Preparation of the Kemalists for the War against Armenia in 1920”[1]. The article represents the standard views in Armenia concerning the military conflicts during the 1919-1920 period in that it entirely lacks critical reflection and attempts to lay the blame for Armenia’s misfortunes on others. In addition, the article has numerous errors of fact and misrepresentations.

According to Safrastyan, the Young Turk Government had recognized the existence of “Western Armenia” in a “January 1914” agreement, but the Kemalist Ankara Government (Grand National Assembly of Türkiye Government) had rejected its existence. This is a blatant distortion of the historical record. To begin with, the 1914 agreement that Safrastyan refers to was not signed in January but February 1914 and the agreement did not contain any reference to Armenia (whether east or west) or the Armenians. In that agreement, the Young Turk administration merely accepted carrying out reforms under the supervision of the two European Inspectors-General in the Eastern provinces of the Ottoman Empire and certainly did not recognize the existence of a “Western Armenia” on Ottoman territories.

The main argument of Safrastyan’s article is that the preparations to liberate the territory under the occupation of the Armenian forces (such as Kars and Ardahan) began in February 1920, that is, before the signing of the Treaty of Sevres and, therefore, they constituted an act of aggression. In other words, the provisions of the Treaty of Sevres were allegedly used as an excuse to launch a war that had been in fact planned and desired earlier.

This is, however, a gross misrepresentation of the Turkish National Struggle and its aims. The idea and struggle to launch a war of liberation began not after the signing of the Treaty of Sevres, but immediately after it became clear that the Allies (Entente Powers) would not remain true to the principles of the Mudros Armistice and would extend to more territories than they actually occupied during the course of the First World War. They would thus partition the Ottoman Empire, including its Turkish heartland, among themselves and their proxies. The idea to create an Armenian state in Eastern Anatolia, where the Muslims constituted a majority, was conceived at the Paris Peace Conference, much earlier than it was formalized in the Treaty of Sevres.

Already on 14 May 1919, British Prime Minister Lloyd George presented a British plan for a conference in order to partition the Ottoman Empire, which included a resolution to establish an Armenian state in Eastern Anatolia under an American mandate. Therefore, irrespective of the date of the signing date of the Treaty of Sevres, proposals and plans to end the Turkish sovereignty over Eastern Anatolia including Kars and Ardahan were in fact contemplated and the Turkish National Struggle was launched to prevent precisely these plans and proposals.

Regarding Kars and Ardahan, Safrastyan fails to mention that the majority of the population in these provinces were Muslims and they had decided to join the Ottoman Empire with plebiscites held in June 1918 after the Treaty of Brest-Litowsk. Believing that the goodwill of the Allies could be gained via gestures, the Ottoman administration pulled its troops back from these regions after the Mudros Armistice and withdrew itself approximately to the prewar boundary. Following this, the (First) Republic of Armenia had moved troops into the Kars-Ardahan region and also claimed large territories in Eastern Anatolia while committing numerous atrocities against the Muslims in the region.

During all this time, the Ankara Government had tried to reason with the newly born Republic of Armenia and tried to reach an agreement. In other words, the Ankara Government was hoping for the best while preparing for the worst, a war with Armenia, to end the Armenian occupation. Armenia rebuffed and refused all overtures, mistakenly believing in its own military strength while underestimating that of the Ankara Government.

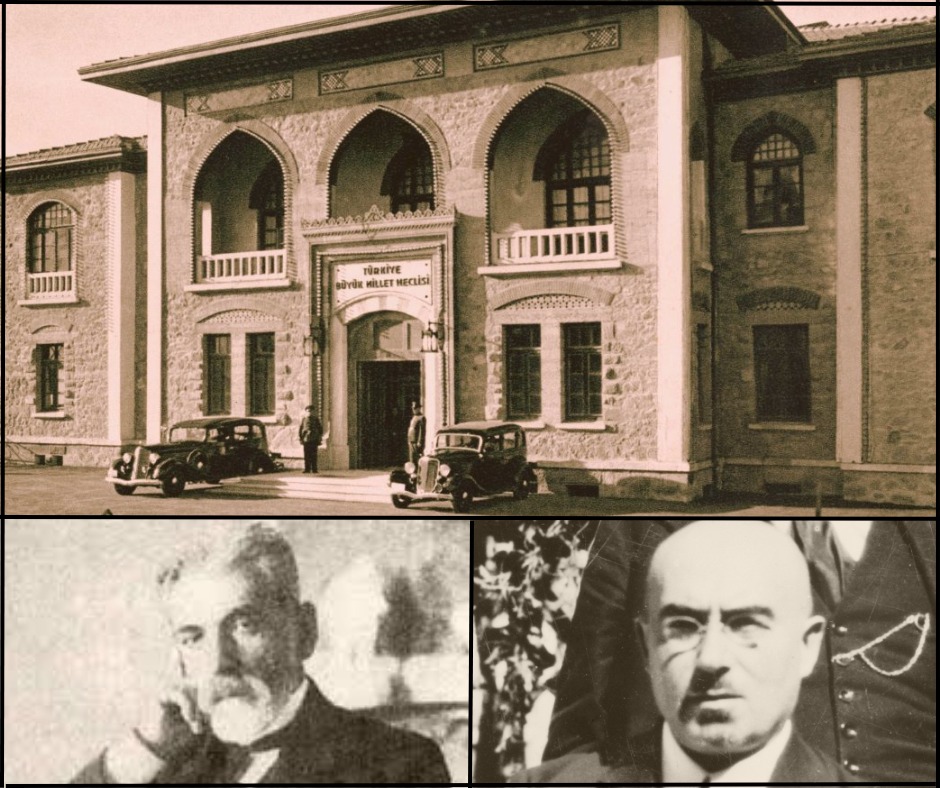

This was also admitted by Alexander Khatisyan, the second Prime Minister of Armenia who was the country’s Minister of Foreign Affairs when the Treaty of Gümrü (Alexandropol) was signed in 1920. Kazım Karabekir, the Turkish Commander in charge of the Eastern Front, told Khatisyan bluntly that had the Armenian Government listened to the Ankara Government and shown willingness to come to terms, then the war would have been avoided and the countries could have started a relationship founded upon peace and mutual respect much earlier. But now that the past was the past, it was time to move on and establish peace and friendly relations between the two countries.[2] Safrastyan ignores this and tries to create a conspiracy when there was none.

This point was also illustrated by Hovhannes Katchaznouni, the first Prime Minister of Armenia, in his well-known manifesto:

“[T]here remains an irrefutable fact. That we had not done all that was necessary for us to have done to evade war. We ought to have used peaceful language with the Turks whether we succeeded or not, and we did not do it. We did not do it for the simple reason — no less culpable — that we had no information about the real strength of the Turks and relied on ours. This was the fundamental error. We were not afraid of war because we thought we would win. With the carelessness of inexperienced and ignorant men we did not know what forces Turkey had mustered on our frontiers. When the skirmishes had started the Turks proposed that we meet and confer. We did not do so and defied them.”[3]

Thus, as Katchaznouni admits, the Armenian leaders refused all the attempts to reach a diplomatic solution since they thought they would win the war. Moreover, even after the clashes started, the Turks wanted to meet and negotiate to reach a settlement, but the Armenian leaders refused any discussions. All of these illustrate the shaky foundations of the Safrastyan’s main thesis.

Safrastyan fails to notice and mention that the main factor was that the Dashnak Armenian leaders of the newly born Republic of Armenia had lost sight of reality and became obsessed with unrealistic, unachievable goals. The Armenian leaders’ conviction that they deserved to rule the region rested to a great extent on the expectation that the sympathy of the foreign powers lay with the Armenians. The Wilson Principles, the proposals of the Paris Peace Conference, as well as the provisions of the Treaty of Sevres had created in them the expectation that they could achieve the impossible. In particular, the “Wilsonian Armenia” plan had blinded them to the realities on the ground.

“Wilsonian Armenia” was the brainchild of US President Woodrow Wilson, under whose influence the US Department of State proposed creating an Armenian state, which was subsequently embraced by all the Entente Powers at the Treaty of Sevres, encompassing virtually all of Eastern Anatolia alongside large regions in the Caucasus at the expense of both the Anatolian and Azerbaijani Turks.

The areas they claimed as Armenia in Eastern Anatolia, including Kars and Ardahan, were only 20 to 25 percent Armenian. A majority of the population, around 80 percent, did not wish to be subjected to Armenian rule and would never accept it. As the American historian and demographer Justin McCarthy notes, the Armenians constituted somewhere around 20 percent of the total population in Eastern Anatolia and even if all the Armenians in the world had settled in Eastern Anatolia, they would have still remained a minority in this region.[4] Therefore, no self-respecting government, no matter how conciliatory, could accept Armenian demands over these regions.

It was not just the Turks or the Ankara Government that knew that these terms were impossible to accept. The British Government, the main victor of the First World War, saw the impossible situation and shrewdly wanted the Americans to take the responsibility for the region rather than working for the impossible themselves. When US President Wilson came up with his proposition to form an Armenia with maximum possible borders in the region, the British Foreign Office mocked his proposals as “Wilson’s castle in the air.”

If the Dashnak Armenian leaders could have brought themselves to face and recognize the realities on the ground, they would have heeded the Turkish offers to negotiate seriously and thereby avoided the war. They would have obtained better terms, and most importantly, would have conserved their military material and soldiers to better resist the subsequent Bolshevik takeover. This point was also admitted by a prominent Armenian historian, Jirair Libaridian:

“We have forgotten how we lost the First Republic of Armenia. There was the Turkish-Russian cooperation. There also was the pursuit of the Treaty of Sevres. Then, as now, we became obsessed with our dreams instead of focusing on the possible, and we lost part of what was possible. More, we lost our independence. In other words, all of this was predictable and predicted.”[5]

It is to be hoped that the future generations in Armenia will heed the warnings and advice of Katchaznouni, Khatisyan, and Libaridian rather than follow the simplistic and distorted version presented by Safrastyan.

*Picture: The first building of the Grand National Assembly of Türkiye (top), Hovhannes Katchaznouni (bottom left), Alexander Khatisyan (bottom right)

[1] Ruben Safrastyan, “Preparation of the Kemalists for the War against Armenia in 1920”, Sciences of Europe, No: 103 (2022): 64-67, https://www.europe-science.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/Sciences-of-Europe-No-103-2022.pdf

[2] Mehmet Arif Demirer (ed.), Hatisyan, 1930 (Ankara: Sonçağ Yayınları, 2021), 317.

[3] Hovhannes Katchaznouni, The Manifesto of Hovhannes Katchaznouni, First Prime Minister of the Independent Armenian Republic (İstanbul: Kaynak Yayınları, 2006).

[4] Justin McCarthy, Turks and Armenians: Nationalism and Conflict in the Ottoman Empire (Madison, Wisconsin/USA: Turko-Tatar Press, 2015).

[5] Jirair Libaridian, "A step, this time a big step, backwards," Aravot, September 1, 2020, https://www.aravot-en.am/2020/09/01/263436/

© 2009-2025 Center for Eurasian Studies (AVİM) All Rights Reserved

No comments yet.

-

CHAPTER BY CHAPTER SYNOPSIS AND REVIEW OF TURKS AND ARMENIANS: NATIONALISM AND CONFLICT IN THE OTTOMAN EMPIRE BY JUSTIN MCCARTHY - 3

CHAPTER BY CHAPTER SYNOPSIS AND REVIEW OF TURKS AND ARMENIANS: NATIONALISM AND CONFLICT IN THE OTTOMAN EMPIRE BY JUSTIN MCCARTHY - 3

Seher ÇELEN 22.10.2015 -

NEW LEADERS FOR THE EUROPEAN UNION HAVE BEEN APPOINTED

NEW LEADERS FOR THE EUROPEAN UNION HAVE BEEN APPOINTED

Hazel ÇAĞAN ELBİR 06.08.2019 -

GENOCIDE ACCUSATION AS A FORM OF PUNISHMENT - III

GENOCIDE ACCUSATION AS A FORM OF PUNISHMENT - III

Mehmet Oğuzhan TULUN 27.04.2021 -

2025 MUNICH SECURITY CONFERENCE AND THE NECESSITY OF CONSTRUCTIVE EURASIANISM

2025 MUNICH SECURITY CONFERENCE AND THE NECESSITY OF CONSTRUCTIVE EURASIANISM

Teoman Ertuğrul TULUN 28.02.2025 -

POPE LEO XIV’S NOVEMBER 2025 VISIT TO TÜRKİYE: A PUSH FOR ECUMENISM IN THE CONTEXT OF A SPIRITUAL JOURNEY

POPE LEO XIV’S NOVEMBER 2025 VISIT TO TÜRKİYE: A PUSH FOR ECUMENISM IN THE CONTEXT OF A SPIRITUAL JOURNEY

Mehmet Oğuzhan TULUN 12.01.2026

-

25.01.2016

THE ARMENIAN QUESTION - BASIC KNOWLEDGE AND DOCUMENTATION -

12.06.2024

THE TRUTH WILL OUT -

27.03.2023

RADİKAL ERMENİ UNSURLARCA GERÇEKLEŞTİRİLEN MEZALİMLER VE VANDALİZM -

17.03.2023

PATRIOTISM PERVERTED -

23.02.2023

MEN ARE LIKE THAT -

03.02.2023

BAKÜ-TİFLİS-CEYHAN BORU HATTININ YAŞANAN TARİHİ -

16.12.2022

INTERNATIONAL SCHOLARS ON THE EVENTS OF 1915 -

07.12.2022

FAKE PHOTOS AND THE ARMENIAN PROPAGANDA -

07.12.2022

ERMENİ PROPAGANDASI VE SAHTE RESİMLER -

01.01.2022

A Letter From Japan - Strategically Mum: The Silence of the Armenians -

01.01.2022

Japonya'dan Bir Mektup - Stratejik Suskunluk: Ermenilerin Sessizliği -

03.06.2020

Anastas Mikoyan: Confessions of an Armenian Bolshevik -

08.04.2020

Sovyet Sonrası Ukrayna’da Devlet, Toplum ve Siyaset - Değişen Dinamikler, Dönüşen Kimlikler -

12.06.2018

Ermeni Sorunuyla İlgili İngiliz Belgeleri (1912-1923) - British Documents on Armenian Question (1912-1923) -

02.12.2016

Turkish-Russian Academics: A Historical Study on the Caucasus -

01.07.2016

Gürcistan'daki Müslüman Topluluklar: Azınlık Hakları, Kimlik, Siyaset -

10.03.2016

Armenian Diaspora: Diaspora, State and the Imagination of the Republic of Armenia -

24.01.2016

ERMENİ SORUNU - TEMEL BİLGİ VE BELGELER (2. BASKI)

-

AVİM Conference Hall 24.01.2023

CONFERENCE TITLED “HUNGARY’S PERSPECTIVES ON THE TURKIC WORLD"