Our previous article on the European Court of Human Rights (ECtHR) Grand Chamber’s judgment on Perinçek v. Switzerland case aimed to provide the reader with the basics of the case and the judgment. As said in that article, further articles were to come to analyze the background of the ECtHR Grand Chamber judgment, detail important aspects of this judgment, asses the positions and arguments of parties and make projections on the evolution of the ‘genocide politics’.

This article, first, briefly discloses the ECtHR Grand Chamber’s undertaking of the Article 17 of the European Convention of Human Rights (ECHR) in relation to the Perinçek v. Switzerland case. Then, it brings up the arguments that Switzerland and Perinçek asserted, yet rejected by the ECtHR Grand Chamber.

The ECtHR made its final judgment by examining two main claims of Switzerland on the imperatives of protection of the “rights of others” and “public order”. The rest of the article deals with Switzerland’s claim of “the prevention of disorder” to justify the criminal conviction of Perinçek and the counter-arguments of the ECtHR Grand Chamber against this reason. Finally, the article draws some partial conclusions from the rejection of this particular claim and asks few hypothetical questions with the hope to highlight some critical issues with respect to the relationship between the rejection of the characterization of 1915 events as genocide and public order.

Article 17

The first step of the ECtHR Grand Chamber was to determine whether to accept or reject the application of Doğu Perinçek. To do that, the ECtHR Grand Chamber, examined Perinçek’s case in reference to the Article 17 of the ECHR that frames the “prohibition of abuse of rights” that states:

Nothing in this Convention may be interpreted as implying for any State, group or person any right to engage in any activity or perform any act aimed at the destruction of any of the rights and freedoms set forth herein or at their limitation to a greater extent than is provided for in the Convention.

The ECtHR Grand Chamber decided that Perinçek “had not used his freedom of expression for ends contrary to the text and spirit[1]” of the ECHR by pointing out that:

- His speeches “did not amount to incitement of hatred towards the Armenian people”

- “[Perinçek] had not expressed contempt towards the victims of the events of 1915 and the following years”

- “[Perinçek] had not been prosecuted for seeking to justify a genocide.[2]

Article 16

By referring to Article 16 of the ECHR, Switzerland suggested that Perinçek was an “alien” (i.e. not a Swiss citizen), hence not under the protection of Articles 10, 11 and 14 of the ECHR. The ECtHR Grand Chamber rejected this argument by stating that Article 10 para. 1 of the ECHR guarantees freedom of expression “regardless of frontiers” and both “nationals” and “foreigners” are protected by the ECHR.

Lawfulness of the Interference to Freedom of Expression: Predictability of Criminal Conviction with respect to the Swiss Penal Code Article 261bis para 4

Perinçek in his appeal underlined that the Swiss court in 2001 judged differently on a similar case to assert lack of standards, hence predictability in the Swiss legal system. He reminded the court that neither the Swiss Council of States had not reached to an agreement on the characterization of the 1915 events nor was there a judgment of a competent court that establishes these events as genocide. Upon these, Perinçek argued that his criminal conviction for ‘denying the Armenian genocide’ was not predictable.

The Turkish Government that interfered to the case as third party followed Perinçek’s previous objection and claimed Perinçek’s criminal conviction was not foreseeable for the vagueness of the Swiss law. The Turkish Government underlined that genocide was a well-defined legal concept and Switzerland already recognized the legal dimension of the term. However, the Turkish Government added, Swiss courts nevertheless relied on “the large consensus on that point in Swiss society”.[3] According to the Turkish Government “the salient point for these courts had thus been not whether these events had indeed amounted to a genocide but whether Swiss society so believed”.[4] The Turkish Government stressed that “however, the problem with determining that point by reference to societal consensus, which could be a fast-changing thing, was that there were no legal criteria providing guidance in this respect. Such vagueness was incompatible with legal certainty”.[5] The Turkish Government argued that in Perinçek case, “law” was given up for “public opinion”. It also underlined that Swiss Government, as well as many other governments did not refer to 1915 events as genocide and there was a controversy among historians on the characterization of the 1915 events. Because of these, the Turkish Government reasoned, Perinçek could not foresee his criminal conviction.

The Swiss Government rejected the claims of absence of clarity in the Swiss law. Notably, “the Swiss Government also pointed out that Article 261 bis § 4 made it an offence to deny both genocide and crimes against humanity, adding that there could be little dispute that the atrocities against the Armenians had constituted such crimes. On this basis, they concluded that that Article was formulated with sufficient precision.”[6] Yet, it has to be noted with precision that genocide and crime against humanity are two different crimes, which cannot substitute one another. Yet, it is a relatively new strategy of the ‘genocide lobby’ to create an ambiguity between these two crimes, gradually frame the 1915 events as crime against humanity, and to establish 1915 events as genocide via crime against humanity out of the awareness that 1915 events can very hardly be characterized as a genocide by a competent court defined in Article 6 of the 1948 Genocide Convection. What is striking is that the Swiss Government in its submission simply acts as a pawn of this strategy.

The ECtHR Grand Chamber accepted that there was a certain degree of ambiguity in Swiss law.[7] Yet, it stated that an “absolute precision in the framing of laws” was impossible.[8] As to the Swiss law, the ECtHR Grand Chamber stated that reviewing and/or correcting domestic law was not its task.[9] As such, the ECtHR refrained from making claims on the Swiss law. The ECtHR stated that its duty was limited just with deciding whether Perinçek could predict that he could be subjected to criminal investigation for his speeches. It decided that Perinçek, was aware of such a possibility and made his speeches with this awareness.

Switzerland’s Arguments: “Rights of Others” and “Public Order”

Switzerland based its arguments on the correctness of the criminal convinction of Perinçek by the Swiss courts on two pillars: 1) prevention of public order, 2) protection of the rights of others, namely: “the honour of the relatives of the victims of the atrocities perpetrated by the Ottoman Empire against the Armenian people from 1915 onwards”[10]. These two became the main points that the ECtHR Grand Chamber examined to reach a final decision on Perinçek v. Switzerland case.

The Prevention of Disorder

The ECtHR Grand Chamber rejected Switzerland’s justification of Perinçek’s criminal conviction on the ground of “the prevention disorder” in the Swiss society rather without much difficulty compared to the issue of “protection of the rights of others”. It brought forward three explanations in a straight forward manner.

Switzerland brought forward the “two opposing rallies held in Lausanne on 24 July 2004” as examples of social disorder erupted out of the ‘genocide issue’. Yet the ECthR Grand Chamber observed that the Swiss Government “did not provide any details in respect of that, and there is no evidence that confrontations had in fact taken place at those rallies.”[11] The ECtHR also underlined that, Swiss courts in their verdicts did not mention those events and it was only the Switzerland-Armenia Association that complained about those rallies. The ECtHR maintained that Swiss authorities did not perceive “those events as capable of leading to public disturbances and attempted to regulate them on that basis.”[12] Lastly, the ECtHR Grand Chamber stated that there was no evidence showing that “in spite of the presence of both Armenian and Turkish communities in Switzerland, this kind of statements could risk unleashing serious tensions and giving rise to clashes”.[13]

Partial Conclusions and Some Hypothetical Questions

It can be seen from the ECtHR Grand Chamber’ undertaking of the argument of “the prevention of disorder” that was brought forward by Switzerland as a justification of Perinçek’s criminal conviction that the ECtHR Grand Chamber limits its task basically with examining the tangible consequences of the deeds in question. It refrains from making “in principle”, in other words “universal”, judgments in reference to possibilities or hypothetical situations. In that sense, the ECtHR Grand Chamber has a strict empirical approach. This approach is also evident in its tackling with the issue “rights of others”, which we shall examine in the following article. In brief, ECtHR examined the real facts and decided that Perinçek’s did not cause any social disorder in Switzerland. Upon this empirical observation, the ECtHR invalidated Switzerland’s argument. Overall, the ECtHR refrains from making “in principle” judgments, as well as theoretical deductions; it assesses the case by examining its real consequences.

However, this empiricist approach carries its own problems, notwithstanding its merits. Furthermore, such an empiricist approach leaves the door open to abuses, at least hypothetically.

Imagine a hypothetical, but possible situation. Perinçek or anyone else makes the same speeches with the same intentions in the same Swiss context and some aggressors, be they xenophobic neo-Nazis or Islamophobic bigots or Armenian nationalists, raid into the conference halls and create uproar, no matter whether these are isolated and spontaneous events or an organized ones. Should such disturbances be the justification of restriction of the freedom of expression? What if, some radicals began provocations at conference halls in which different views on the 1915 events are discussed in order to delegitimize and/or criminalize dissident views? If that happens, would the freedom of expression be interfered? Should Martin Luther King, Jr. across the Atlantic have been criminalized just because his ‘dream’ of equality between the Euro-Americans and Afro-Americans provoked the anger and terror of the racist white supremacists, hence public disturbances in the States?

One may think that the above mentioned hypothetical scenarios are too hypothetical. However, those who are familiar with the history of ‘genocide politics’ know just too well that these hypothetical scenarios are not too fictitious. The terror wave launched by the Armenian Secret Army for the Liberation of Armenia (ASALA) and the Justice Commandos for Armenian Genocide-Armenian Revolutionary Army (JCAG-ARA) between mid-1970s and mid-1980s is a well-documented historical episode.

At the moment, there is no sign of another wave of terror. However, small scale assaults of the Armenian nationalists are being recorded. Just to remind few examples, on 2 March 2015 a French-Armenian protestor threw a red-liquid on Turkey’s ambassador to Paris Hakkı Akil while he was giving a speech in a university in Paris. On 15 June 2015, in Lyon a group of Armenian youth, who were the members of the Armenian Revolutionary Federation-Dashnaksutyun made a sit-in protest and shouted slogans in front of the Turkish stand at the Consulates’ Fest.

Certainly, peaceful protest is a democratic right and everyone should have the right of democratic protest. This is an integral part of the ideal of freedom of expression. Nevertheless, here the point is what would happen if these protests are organized in a manner to disturb public order whenever alternative views on the 1915 events are expressed? What if some radicals do that on purpose? If such a thing, happens should the ECtHR Grand chamber or another court accept the restriction of the freedom of expression as a legitimate and lawful act? Would such a decision not mean to put the blame to the blameless that just exercises her/his freedom of expression? Would that not mean to award provocateurs?

These are some questions that the reasoning of the ECtHR Grand Chamber raises. They are hypothetical, but not fictitious questions.…

The next article will focus on the issue of “rights of others”, which is a more complicated and consequential issue compared to “the prevention of disorder” that the ECtHR dealt at length. “Rights of others” is likely to extend into other relevant issues that may require to be dealt with in separate articles.

[1] ECtHR Grand Chamber Judgment on the Case of Perinçek v. Switzerland (Application no. 27510/08) on 15 October 2015, para. 104.

[2] Ibid.

[3] ECtHR Grand Chamber Judgment on the Case of Perinçek v. Switzerland (Application no. 27510/08) on 15 October 2015,Para. 129.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid.

[6] ECtHR Grand Chamber Judgment on the Case of Perinçek v. Switzerland (Application no. 27510/08) on 15 October 2015,Para 127.

[7] ECtHR Grand Chamber Judgment on the Case of Perinçek v. Switzerland (Application no. 27510/08) on 15 October 2015,Para 138.

[8] ECtHR Grand Chamber Judgment on the Case of Perinçek v. Switzerland (Application no. 27510/08) on 15 October 2015,Para 133.

[9] ECtHR Grand Chamber Judgment on the Case of Perinçek v. Switzerland (Application no. 27510/08) on 15 October 2015,Para 136.

[10] ECtHR Grand Chamber Judgment on the Case of Perinçek v. Switzerland (Application no. 27510/08) on 15 October 2015,Para 141.

[11] ECtHR Grand Chamber Judgment on the Case of Perinçek v. Switzerland (Application no. 27510/08) on 15 October 2015,Para 153.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Ibid.

© 2009-2025 Center for Eurasian Studies (AVİM) All Rights Reserved

No comments yet.

-

BECOMING THE PART OF THE PROBLEM: THE FAULTY POLICIES OF THE WEST IN EURASIA AND THE SOUTH CAUCASUS

BECOMING THE PART OF THE PROBLEM: THE FAULTY POLICIES OF THE WEST IN EURASIA AND THE SOUTH CAUCASUS

Turgut Kerem TUNCEL 11.08.2015 -

THE FIGHT OF FRANCE AGAINST FRANCE AND THE FUTURE OF EUROPE

THE FIGHT OF FRANCE AGAINST FRANCE AND THE FUTURE OF EUROPE

Turgut Kerem TUNCEL 22.02.2019 -

PASHINYAN'S GERMANY VISIT

PASHINYAN'S GERMANY VISIT

Turgut Kerem TUNCEL 09.03.2023 -

AN INQUIRY INTO NANCY PELOSI’S VISIT TO ARMENIA

AN INQUIRY INTO NANCY PELOSI’S VISIT TO ARMENIA

Turgut Kerem TUNCEL 23.09.2022 -

THE KARABAKH CONFLICT AND THE LAWFARE OF ARMENIA: ARMENIA’S CAMPAIGN FOR REMEDIAL SECESSION (I)

THE KARABAKH CONFLICT AND THE LAWFARE OF ARMENIA: ARMENIA’S CAMPAIGN FOR REMEDIAL SECESSION (I)

Turgut Kerem TUNCEL 27.10.2020

-

THE BALTIC COUNTRIES: 25 YEARS OF ACCOMPLISHMENT AND FEAR

THE BALTIC COUNTRIES: 25 YEARS OF ACCOMPLISHMENT AND FEAR

Teoman Ertuğrul TULUN 07.12.2016 -

THE NAGORNO-KARABAKH ISSUE FROM A JURIDICAL POINT OF VIEW: THE CASE OF CHIRAGOV AND OTHERS V. ARMENIA

THE NAGORNO-KARABAKH ISSUE FROM A JURIDICAL POINT OF VIEW: THE CASE OF CHIRAGOV AND OTHERS V. ARMENIA

Turgut Kerem TUNCEL 26.06.2015 -

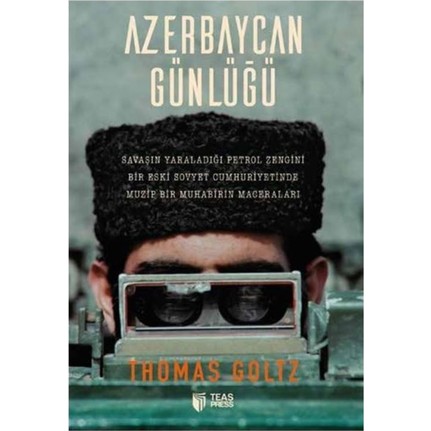

BOOK REVIEW: AZERBAIJAN DIARY: A ROGUE REPORTER'S ADVENTURES IN AN OIL-RICH, WAR-TORN, POST-SOVIET REPUBLIC

BOOK REVIEW: AZERBAIJAN DIARY: A ROGUE REPORTER'S ADVENTURES IN AN OIL-RICH, WAR-TORN, POST-SOVIET REPUBLIC

Nigar SHİRALİZADE 20.07.2018 -

REASSESSING ARMENIA’S CONSTITUTIONAL ALIGNMENT WITH INTERNATIONAL NORMS

REASSESSING ARMENIA’S CONSTITUTIONAL ALIGNMENT WITH INTERNATIONAL NORMS

Teoman Ertuğrul TULUN 20.09.2024 -

GUARDIANSHIP OR EQUILIBRIUM? POWER, AND THE LEGACY OF ORDER IN THE BLACK SEA

GUARDIANSHIP OR EQUILIBRIUM? POWER, AND THE LEGACY OF ORDER IN THE BLACK SEA

Teoman Ertuğrul TULUN 02.09.2025

-

25.01.2016

THE ARMENIAN QUESTION - BASIC KNOWLEDGE AND DOCUMENTATION -

12.06.2024

THE TRUTH WILL OUT -

27.03.2023

RADİKAL ERMENİ UNSURLARCA GERÇEKLEŞTİRİLEN MEZALİMLER VE VANDALİZM -

17.03.2023

PATRIOTISM PERVERTED -

23.02.2023

MEN ARE LIKE THAT -

03.02.2023

BAKÜ-TİFLİS-CEYHAN BORU HATTININ YAŞANAN TARİHİ -

16.12.2022

INTERNATIONAL SCHOLARS ON THE EVENTS OF 1915 -

07.12.2022

FAKE PHOTOS AND THE ARMENIAN PROPAGANDA -

07.12.2022

ERMENİ PROPAGANDASI VE SAHTE RESİMLER -

01.01.2022

A Letter From Japan - Strategically Mum: The Silence of the Armenians -

01.01.2022

Japonya'dan Bir Mektup - Stratejik Suskunluk: Ermenilerin Sessizliği -

03.06.2020

Anastas Mikoyan: Confessions of an Armenian Bolshevik -

08.04.2020

Sovyet Sonrası Ukrayna’da Devlet, Toplum ve Siyaset - Değişen Dinamikler, Dönüşen Kimlikler -

12.06.2018

Ermeni Sorunuyla İlgili İngiliz Belgeleri (1912-1923) - British Documents on Armenian Question (1912-1923) -

02.12.2016

Turkish-Russian Academics: A Historical Study on the Caucasus -

01.07.2016

Gürcistan'daki Müslüman Topluluklar: Azınlık Hakları, Kimlik, Siyaset -

10.03.2016

Armenian Diaspora: Diaspora, State and the Imagination of the Republic of Armenia -

24.01.2016

ERMENİ SORUNU - TEMEL BİLGİ VE BELGELER (2. BASKI)

-

AVİM Conference Hall 24.01.2023

CONFERENCE TITLED “HUNGARY’S PERSPECTIVES ON THE TURKIC WORLD"