On October 17, a triple trial took place at the Paris tribunal (17th chamber, medias chamber). The trial involved Maxime Gauin, scholar in residence at AVİM, against Jean-Marc “Ara” Toranian, chief of the political branch of the ASALA in France from 1976 to 1983, currently co-chairman of the Coordination Council of France’s Armenian Associations and editor of the monthly Les Nouvelles d’Arménie magazine, and Samuel Tilbian, treasurer of the Federation of Armenian Associations in Rhône-Alpes (Lyon’s region).

The first case is against Mr. Toranian and Mr. Tilbian together, the second for having written defamatory words, the first for having not removed the message until two months had passed, in spite of the fact that he was (and still is) the editor of the website. In the said message, Maxime Gauin was called “a true hack at the service of Turkish Fascism” and “a certified denialist.”

The second case is against Mr. Tilbian only, regarding his messages calling the same victim “a pathetic civil servant of the Turkish Fascist administration, whose IQ must be barely 75,” one of “those [who] make Nazism an efficient machine,” and who was “hired by the Turkish Fascist state as professional falsifier in historical matters,” and “a Faurisson, a Dieudonné, a Soral.” To inform the reader; Robert Faurisson is one of the most famous Holocaust deniers,[1] Dieudonné M’Bala M’Bala has been sentenced several times for incitement to hatred and insult against the Jews (including for a short show with Robert Faurisson),[2] and Alain Soral is a writer who turned to the far right around 2004, and who too has been sentenced several times for defamation and for making racist statements.[3]

The third case is against Mr. Toranian only, for three excerpts of an editorial he published on his website, one accusing his victim being able to write anything and its opposite according to the audience, one accusing the victim of spreading “the denialist theses of Turkey on the Armenian genocide,” and one comparing him with Robert Faurisson.

A part of these attacks that have been sued by the victim, Maxime Gauin, as defamation, and the rest (those who are not articulated on precise facts, such as “Faurisson, Dieudonné, Soral”) as insults, in conformity with the French Law of 29 July 1881 that establishes the distinction between defamation and insult, and of the Constant Case Law that considers a general attack against honor -without concrete accusation- to be an insult. No offer of evidence was filed for the said defamatory words. As a result, the defense argued on good faith only, and even pretended (without any basis) that the traditional criteria for good faith (a minimum of factual basis, prudence in the wording, absence of personal animosity, legitimacy of the pursued goal) are not required anymore. Instead of engaging in any discussion on Maxime Gauin’s scholarly publications, the defense made general attacks against Turkey, tried to link the plaintiff with the Turkish state (without any evidence) and made irrelevant references to Holocaust denial. There was no attempt to discuss the decision of the French Constitutional Council in January 2017, ruling that the tragedy of 1915 and the rest of events which were not judged by a French or international court recognized by France “may be the subject of historical debates,”[4] unlike the genocide of the Jews by the Nazi regime.[5] Regarding the European Court of Human Rights’ (ECtHR) Perinçek v. Switzerland case, the defense quoted one irrelevant sentence of the ECtHR Second Chamber decision, and completely ignored the distinction made by the ECtHR between the controversy regarding 1915 and Holocaust denial:

“175. […] The Swiss Government had not duly showed that this rejection had promoted racial discrimination of the Armenian community in Switzerland, and there was no basis automatically to infer from it racist and nationalistic motives or an intention to discriminate. The main difference in this respect with statements relating to the Holocaust, whose denial today was one of the main vehicles of anti-Semitism, was the lack of connection between past and present hate. […]

231. […] He [Doğu Perinçek] took part in a long-standing controversy that the Court has, in a number of cases against Turkey, already accepted as relating to an issue of public concern (see paragraphs 221 and 223 above), and described as a ‘heated debate, not only within Turkey but also in the international arena’ (see paragraph 224 above).”[6]

Correspondingly, the two defense witnesses, Yves Ternon and Raymond Kévorkian, did not make any criticism of Maxime Gauin’s work and were not able to give a single example of falsification. Regarding the insults, the defense did not try argue that there is the excuse of provocation (unlike Movsès Nissanian’s failed defense against the same Maxime Gauin in 2009-2010),[7] but just pretended that they are not insults, but rather opinions, or at worst, defamations. The defense tried to compensate this extreme legal weakness with a lot of pathos, and the defendants shamelessly presented themselves as victims of “Turkish denialism.”

Jean-Marc “Ara” Toranian and Samuel Tilbian are defended by Henri Leclerc, who previously defended JCAG and ASALA terrorists in France, together with Patrick Devedjian.[8] Maxime Gauin is defended by Patrick Maisonneuve, the counsel of the Managing Director of the International Monetary Fund Christine Lagarde and tennis player Rafael Nadal. The verdict will be pronounced on November 28, 2017.

[1] See, e.g., Faurisson v. France, Communication No. 550/1993, U.N. Doc. CCPR/C/58/D/550/1993(1996) (November 8, 1996), accessed November 1, 2017, http://hrlibrary.umn.edu/undocs/html/VWS55058.htm

[2] See, e.g., M’Bala M’Bala c. France, No. n° 25239/13 (European Court of Human Rights, October 20, 2015), accessed November 1, 2017, http://hudoc.echr.coe.int/eng?i=001-158752

[3] See, e.g., LDH c. Soral (Cour d’appel de Paris, June 11, 2008), accessed November 1, 2017, https://fr.scribd.com/document/282493019/Arret-de-la-cour-d-appel-de-Paris-2008

[4] Décision n° 2016-745 DC du 26 janvier 2017, § 196 (Conseil Constitutionnel de la République Française), accessed November 1, 2017, http://www.conseil-constitutionnel.fr/conseil-constitutionnel/francais/les-decisions/acces-par-date/decisions-depuis-1959/2017/2016-745-dc/decision-n-2016-745-dc-du-26-janvier-2017.148543.html

[5] Décision n° 2015-512 QPC du 8 janvier 2016 (Conseil Constitutionnel de la République Française), accessed November 1, 2017, http://www.conseil-constitutionnel.fr/conseil-constitutionnel/francais/les-decisions/acces-par-date/decisions-depuis-1959/2016/2015-512-qpc/decision-n-2015-512-qpc-du-8-janvier-2016.146840.html

[6] Perinçek v. Switzerland, No. Application no. 27510/08 (European Court of Human Rights, Grand Chamber October 15, 2015), accessed November 1 ,2017, http://hudoc.echr.coe.int/eng?i=001-158235

[7] Gauin c. Nissanian (Tribunal de grande instance de Lyon, April 27, 2010), accessed November 1, 2017, http://www.legipresse.com/media/272-06.pdf

[8] See, e.g., Comité de soutien à Max Kilndjian, Les Arméniens en cour d’assises. Terroristes ou résistants ? (Roquevaire : Parenthèses, 1983) ; “Quatre Arméniens devant leurs juges — Le Commando suicide Yeghin Kechichian répond de l’occupation sanglante du consulat de Turquie à Paris le 24 septembre 1981”, Le Monde, January 23, 1984 ; “Procès des boucs émissaires de la répression anti-arménienne à Créteil”, Hay Baykar, January 12, 1985, pp. 4-9 ; “Bobigny : la solidarité arménienne condamnée”, Hay Baykar, May 10, 1985, pp. 8-9 ; and Markar Melkonian, My Brother’s Road. An American’s Fateful Journey to Armenia (London-New York: I. B. Tauris, 2005), pp. 146-153.

© 2009-2025 Center for Eurasian Studies (AVİM) All Rights Reserved

No comments yet.

-

ARMENIAN POLITICAL THINKING AND A SOBER WAKE-UP CALL BY GERARD LIBARIDIAN

ARMENIAN POLITICAL THINKING AND A SOBER WAKE-UP CALL BY GERARD LIBARIDIAN

AVİM 01.02.2021 -

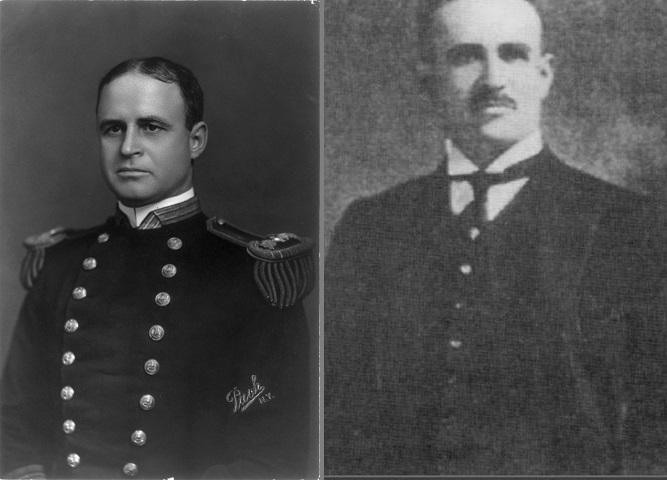

ARMENIAN NATIONALIST PROPAGANDA, THE FALL OF KARS, AND THE KARS TREATY OF 1920

ARMENIAN NATIONALIST PROPAGANDA, THE FALL OF KARS, AND THE KARS TREATY OF 1920

AVİM 13.01.2022 -

ROVING REVOLUTIONARIES OR TERRORISTS?

ROVING REVOLUTIONARIES OR TERRORISTS?

AVİM 12.03.2020 -

FREEDOM OF EXPRESSION

FREEDOM OF EXPRESSION

AVİM 21.06.2015 -

LEGAL AND STRATEGIC APPROACHES AGAINST GENOCIDE ALLEGATIONS: ESTABLISHING A MIDDLE PATH

LEGAL AND STRATEGIC APPROACHES AGAINST GENOCIDE ALLEGATIONS: ESTABLISHING A MIDDLE PATH

AVİM 21.03.2025

-

ARMENIA IS ON THE RIGHT TRACK

ARMENIA IS ON THE RIGHT TRACK

AVİM 14.05.2024 -

NUMBER 21 OF THE REVIEW OF ARMENIAN STUDIES HAS BEEN PUBLISHED

AVİM 27.07.2010 -

THE NSU CASE IS FAR FROM CONSTITUTING A BEGINNING OF A RESOLUTION REGARDING THE XENOPHOBIA IN EUROPE

THE NSU CASE IS FAR FROM CONSTITUTING A BEGINNING OF A RESOLUTION REGARDING THE XENOPHOBIA IN EUROPE

Hazel ÇAĞAN ELBİR 02.08.2018 -

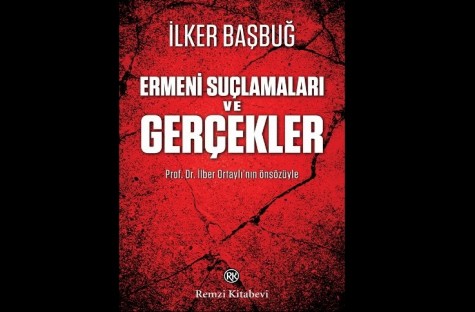

BOOK REVIEW: ARMENIAN ALLEGATIONS AND FACTS (ERMENİ SUÇLAMALARI VE GERÇEKLER)

BOOK REVIEW: ARMENIAN ALLEGATIONS AND FACTS (ERMENİ SUÇLAMALARI VE GERÇEKLER)

Ali Murat TAŞKENT 09.07.2015 -

THE OPENING OF TANAP NATURAL GAS PIPELINE

THE OPENING OF TANAP NATURAL GAS PIPELINE

Tutku DİLAVER 14.06.2018

-

25.01.2016

THE ARMENIAN QUESTION - BASIC KNOWLEDGE AND DOCUMENTATION -

12.06.2024

THE TRUTH WILL OUT -

27.03.2023

RADİKAL ERMENİ UNSURLARCA GERÇEKLEŞTİRİLEN MEZALİMLER VE VANDALİZM -

17.03.2023

PATRIOTISM PERVERTED -

23.02.2023

MEN ARE LIKE THAT -

03.02.2023

BAKÜ-TİFLİS-CEYHAN BORU HATTININ YAŞANAN TARİHİ -

16.12.2022

INTERNATIONAL SCHOLARS ON THE EVENTS OF 1915 -

07.12.2022

FAKE PHOTOS AND THE ARMENIAN PROPAGANDA -

07.12.2022

ERMENİ PROPAGANDASI VE SAHTE RESİMLER -

01.01.2022

A Letter From Japan - Strategically Mum: The Silence of the Armenians -

01.01.2022

Japonya'dan Bir Mektup - Stratejik Suskunluk: Ermenilerin Sessizliği -

03.06.2020

Anastas Mikoyan: Confessions of an Armenian Bolshevik -

08.04.2020

Sovyet Sonrası Ukrayna’da Devlet, Toplum ve Siyaset - Değişen Dinamikler, Dönüşen Kimlikler -

12.06.2018

Ermeni Sorunuyla İlgili İngiliz Belgeleri (1912-1923) - British Documents on Armenian Question (1912-1923) -

02.12.2016

Turkish-Russian Academics: A Historical Study on the Caucasus -

01.07.2016

Gürcistan'daki Müslüman Topluluklar: Azınlık Hakları, Kimlik, Siyaset -

10.03.2016

Armenian Diaspora: Diaspora, State and the Imagination of the Republic of Armenia -

24.01.2016

ERMENİ SORUNU - TEMEL BİLGİ VE BELGELER (2. BASKI)

-

AVİM Conference Hall 24.01.2023

CONFERENCE TITLED “HUNGARY’S PERSPECTIVES ON THE TURKIC WORLD"