The Guardian (12 September 2019)

It was the trip of a lifetime, a globe-trotting adventure halfway across the world, chronicled online for family and friends back home and for followers online.

But in the eyes of the regime in Tehran – squeezed by sanctions and paranoid about the motives of outsiders – the act of flying a drone near a military installation on the outskirts of the Iranian capital appeared as an act of espionage.

The arrest, 10 weeks ago, of Australian couple Mark Firkin and Jolie King (who also holds a British passport) has cast in stark relief the mistrust that characterises Iran’s view of the west, and foreigners within its borders.

From an external perspective, the couple’s activities were entirely innocent: the harmless, if naive, documenting of their grand adventure driving from Australia to London.

But Tehran saw spying and swooped.

“I don’t think Iran targeted these individuals because they are Australian,” said Prof Shahram Akbarzadeh, research professor of Middle East and Central Asian politics at Deakin University, as details of the couple’s arrest emerged on Thursday. “The authorities in Iran are very suspicious of foreign nationals travelling to Iran if they are producing films or documentaries, interviewing people or taking pictures of sensitive sites. These kinds of activities are seen as having a hidden agenda.

“It speaks to the insecurity, to the paranoia of the ruling regime in Iran. The regime feels under pressure from foreign powers. Even though what this couple is said to have done appears, from the outside, to be mundane, to be benign, to Tehran it looks suspicious, it looks like spying.”

Tehran welcomes tourists – even if only for the much-needed foreign currency they bring – but it wants tight control of their movements and on the picture of Iran they present to the outside world.

Little is publicly known about the arrest and trial of a third Australian currently held in an Iranian jail. The Guardian understands the Cambridge-educated British-Australian academic had been teaching at a university in Melbourne. She was arrested last year and tried (the nature of the charges are not publicly known) and sentenced to 10 years in prison.

She is reportedly being held in solitary confinement in the notorious Evin prison.

Australia’s ability to negotiate on behalf of its citizens held in Iranian jails might once have been relatively strong. But its bargaining position has been weakened by its overt alignment to bellicose American policy in the Middle East.

In August, Australian became only the third country to commit to a US-led coalition patrolling the Strait of Hormuz, the waterway off Iran’s south coast through which about a fifth of the world’s oil passes. Scott Morrison said “destabilising behaviour” – a thinly veiled reference to Iran’s capture of foreign-flagged ships – was a threat to Australian interests.

US officials – including senior figures such as the just-deposed national security adviser John Bolton and the secretary of state Mike Pompeo – have been seen as advocates for regime change in Iran (though Donald Trump has disavowed this publicly).

However this, combined with the US president’s unilateral decision to tear up the Iran nuclear deal (widely regarded as successfully negating Iranian nuclear ambitions) and to reimpose crippling economic sanctions, has squeezed Iran into a political and economic corner.

In recent history, relations between Iran and Australia have been robust, if not always smooth. Australia has maintained diplomatic relations with Tehran through decades where other western nations have abandoned them or they have become acutely strained. After the signing of the nuclear deal in 2015, then foreign affairs minister Julie Bishop was one of the first international figures to visit Tehran.

But those ties have weakened: Australia hosts significant numbers of Iran students (mainly at postgraduate level) but trade between the two countries has diminished in recent years. Australia has few diplomatic levers to pull, Akbarzadeh argues.

“I think Australia’s presence in the Persian Gulf [patrolling with the US] is largely symbolic, it will be small and not very effective,” the professor says. “But it sends a signal and Iran has received that signal: it says Australia is firmly in the US camp and firmly supports the US sanctions on Iran.”

Canberra’s adherence to a hawkish US policy has undermined Australia’s ability to speak to the Iranian government, Akbarzadeh says.

“The leadership in Iran wants to speak to foreign powers on an equal footing, they don’t want to be lectured, talked down to, or coerced into a position of weakness.”

Iran’s foreign affairs minister has previously floated the idea of a prisoner swap, essentially conceding that those foreign nationals held in Iranian jails might be used as hostages in order to free Iranians (there are currently about 12 foreign nationals in Iranian prisons, most holding dual Iranian citizenship not recognised by Tehran).

But significantly, Akbarzadeh argues, the Australians held in Iranian jails are under the control of the country’s judiciary, which historically holds to a much harder line on foreign national prisoners than the foreign ministry does.

Australia has also lost potentially crucial leverage in the form of Iranian citizen Negar Ghodskani, who was held in an Adelaide jail for more than two years while she fought a US extradition request over allegations of sanctions busting.

Ghodskani was eventually extradited. Last month, she pleaded guilty in an American court to being part of a conspiracy to evade US sanctions and illegally export controlled technology. She faces up to five years in jail.

Iran was displeased by Australia’s acquiescence to the US request to arrest Ghodskani in 2017, to the extent of repeatedly summoning Australia’s ambassador to protest her arrest and treatment (Ghodskani was pregnant when arrested and went on to give birth while in prison).

In April this year, while Ghodksani was still in Australia, Iran’s foreign minister Mohammad Javad Zarif publicly canvassed her as a candidate for a prisoner swap for British citizen Nazanin Zaghari-Ratcliffe (though it is unlikely Australia would ever have acceded in the face of US opposition).

But that potential diplomatic leverage is gone, the US alliance on which Australia depends for its security is acutely damaging in Tehran, and Australia has few other levers to pull.

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2019/sep/12/australia-left-with-few-diplomatic-levers-after-three-citizens-detained-in-iran

No comments yet.

- FOREIGN MINISTER SAYS ARMENIA READY TO EXPAND ITS INTERNATIONAL PEACEKEEPING ROLE The Caucasus and Turkish-Armenian Relations 12.09.2019

-

OPEC MEMBERS IRAQ, NIGERIA AGREE TO CUT OIL OUTPUT

Iraq

12.09.2019

OPEC MEMBERS IRAQ, NIGERIA AGREE TO CUT OIL OUTPUT

Iraq

12.09.2019

-

BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA JOINS IN ON TURKISH STREAM

The Balkans

12.09.2019

BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA JOINS IN ON TURKISH STREAM

The Balkans

12.09.2019

- VON DER LEYEN’S COMMISSION: MORE PRESIDENTIALIST, MORE PARLIAMENTARIAN Europe - EU 12.09.2019

-

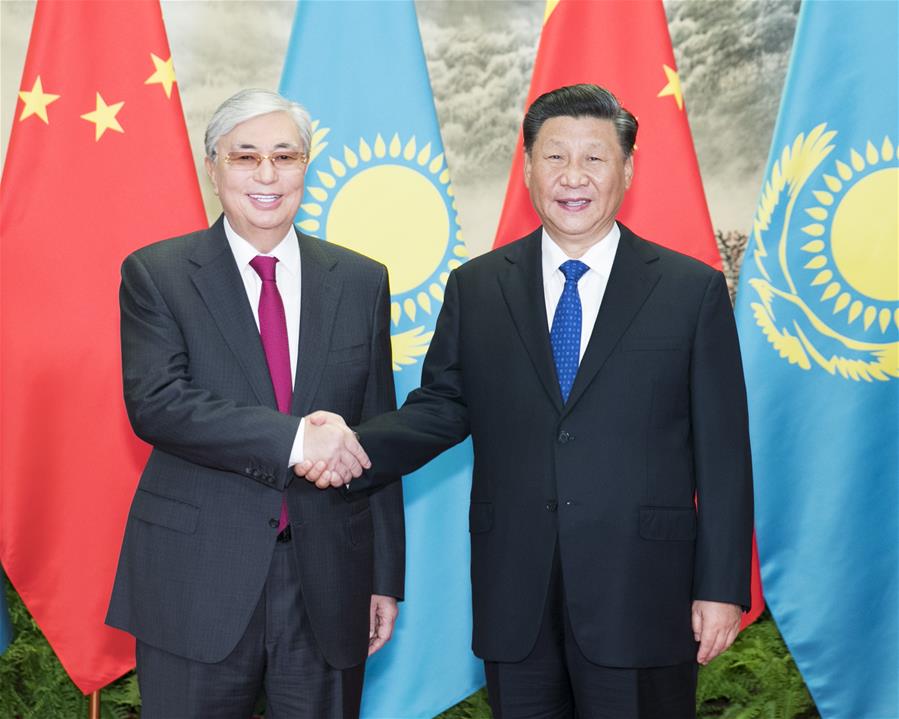

CHINA FOCUS: CHINA, KAZAKHSTAN AGREE TO DEVELOP PERMANENT COMPREHENSIVE STRATEGIC PARTNERSHIP

Asia - Pacific

12.09.2019

CHINA FOCUS: CHINA, KAZAKHSTAN AGREE TO DEVELOP PERMANENT COMPREHENSIVE STRATEGIC PARTNERSHIP

Asia - Pacific

12.09.2019

-

25.01.2016

THE ARMENIAN QUESTION - BASIC KNOWLEDGE AND DOCUMENTATION -

12.06.2024

THE TRUTH WILL OUT -

27.03.2023

RADİKAL ERMENİ UNSURLARCA GERÇEKLEŞTİRİLEN MEZALİMLER VE VANDALİZM -

17.03.2023

PATRIOTISM PERVERTED -

23.02.2023

MEN ARE LIKE THAT -

03.02.2023

BAKÜ-TİFLİS-CEYHAN BORU HATTININ YAŞANAN TARİHİ -

16.12.2022

INTERNATIONAL SCHOLARS ON THE EVENTS OF 1915 -

07.12.2022

FAKE PHOTOS AND THE ARMENIAN PROPAGANDA -

07.12.2022

ERMENİ PROPAGANDASI VE SAHTE RESİMLER -

01.01.2022

A Letter From Japan - Strategically Mum: The Silence of the Armenians -

01.01.2022

Japonya'dan Bir Mektup - Stratejik Suskunluk: Ermenilerin Sessizliği -

03.06.2020

Anastas Mikoyan: Confessions of an Armenian Bolshevik -

08.04.2020

Sovyet Sonrası Ukrayna’da Devlet, Toplum ve Siyaset - Değişen Dinamikler, Dönüşen Kimlikler -

12.06.2018

Ermeni Sorunuyla İlgili İngiliz Belgeleri (1912-1923) - British Documents on Armenian Question (1912-1923) -

02.12.2016

Turkish-Russian Academics: A Historical Study on the Caucasus -

01.07.2016

Gürcistan'daki Müslüman Topluluklar: Azınlık Hakları, Kimlik, Siyaset -

10.03.2016

Armenian Diaspora: Diaspora, State and the Imagination of the Republic of Armenia -

24.01.2016

ERMENİ SORUNU - TEMEL BİLGİ VE BELGELER (2. BASKI)

-

AVİM Conference Hall 24.01.2023

CONFERENCE TITLED “HUNGARY’S PERSPECTIVES ON THE TURKIC WORLD"