Author: Michael A. Reynolds

Published: Türkiye İş Bankası Kültür Yayınları, Ankara, 2016

ISBN:6053328308

Language: Turkish

Number of pages: 378

The Turkish translation of the book “Shattering Empires the Clash and collapse of the Ottoman and Russian Empires 1908–1918”written by Michael A. Reynolds was published in August 2016, by İş Bankası Kültür Yayınları. The book covers crucial periods of two influential but declining empires of the early 20thcentury. Their collapse contributed to the inscription of a new world order with new rules and actors.

Reynold’s book is comprehensive, linking various issues related to the two falling empires and their influence to each other within a single picture. Indeed it seems like by weaving different partials that looks unrelated at the first chance, the author presents a full puzzle to the readers through an interesting narrative. His historical analysis utilizes the terms and concepts of the discipline of international relations to disclose important issues concealed for decades. He adroitly depicted the cracks deepened with upheaval of minor nations supported by great powers appearing in Russian and Ottoman empires in the early 20thcentury that eventually brought them to the crackdown.

Another salient point of Reynold’s work is its ability to resonate with the current problems of the successors of the Tsarist Russia and Ottomans. By emphasizing the games played on the small nations living in these empires the author drew a comprehensive historical background of the current issues related to Armenian and Kurdish problems in Turkey, and Russia’s unimpeded influences in Eastern Europe, Caucasia and Central Asia continuing even today. Thus with the look back to history, Reynolds presents an overview facilitating the apprehension of the current regional relations among the actors occurring in the previous territories of the shattered empires.

The book starts with the activities of the Young Turks(Committee of Union and Progress (CUP)), considering themselves as the “men of destiny” fated to preserve the unity of Ottoman Empire[1]. They believed that the path to the unity goes through progressive reform, therefore the reestablishment of the structure of the empire in the “era of transition” seemed inevitably important.

This group aimed to strengthen the empire rather than deconstruct it. They rightly analyzed that the international system had been going through eminent change. Ottomans got acquainted with this profound transformation in the international order firstly in Berlin conference in 1878. The congress aimed to solve the “Eastern Question” through the partition of the Ottoman empire while escaping from a great power war. Reynolds argued that this congress not only influenced the balance of powers, but also brought a new outlook to the great power diplomacy and statecraft. The issue of ethnicity that had been subordinated by other unification means in the imperial systems turned politically significant after 1878, but it generated new problems especially for shattering powers:

The acknowledgment of ethnicity’s theoretical claim to sovereignty gave rise to the practical problem of what to do with those ethnicities too small or too scattered to endow with statehood. The inevitable byproduct of the idea that legitimate statehood resides in the popular sovereignty of communities defined by ethnicity in a given territory is the disadvantaging of those who share the same territory but are of different ethnicity[2].

The article 61 of the treaty signed in Berlin was related to the rights ofminorities particularly “the Armenians, a Christian people indigenous to Eastern Anatolia and the Caucasus[3].” As Reynolds predicates, this article “singled out Armenians based on ethnicity and granted to outside powers the prerogative to intervene on their behalf[4].”

The author emphasizes that from this time on international forces started to condemn Istanbul for not being able to provide internal security and stability for minorities on the one hand, and continued to assist dissents for nurturing chaos within the empire on the other.

Two ethnic minorities in Ottoman territory played a crucial role in escalating the destabilization, they were Armenians and Kurds. The main proponents of this chaos within Ottoman empire were the Russians, who played dual roles towards both of these ethnic minorities. On the one hand, they tried to gain sympathy of Armenians via supporting their appeals for reforms in eastern Anatolia, on the other hand, they backed up Kurdish dissents through material and financial means. The Foreign Affairs Minister of Tsarist Russia Sergei Sazonov evaluated the Kurds as a “potential power” in Ottoman empire with whom relations should be perpetuated[5].

According to Reynolds, the “Armenian problem” in Ottoman territory was always the Kurdish-Armenian problem. Christian Armenians who had access to better education, living conditions and economic welfare irritated Muslim Kurds suffering from diseases, illiteracy and poverty. In order to grasp Armenian lands and affluence Kurds had incessantly attacked the Armenian communities. Kurds condemned Ottoman authorities due to their inability to provide them with sufficient welfare, on the other hand Armenians saw governmental forces feeble for providing them with efficient security. Consequently, both sides decided to solve their own problems by themselves through armament and with the assistance of foreign forces, especially Russians who were most interested in the chaos within Ottoman empire.

Reynolds points out a very dramatic fact pertained to the armament issue. He argues that during Bitlis uprising in 1914 Ottoman authorities armed Armenians for “fighting against obscurantist” Kurds. Kurdish ringleaders of the revolt took refuge in the Russian Consulate. Russians played an important role for educating and arming not only Kurds, but also Armenians in Anatolia. Thus in this period the Russians played a double game.

The transition in the international system in the early 20thcentury did not pass by the Russian empire either. The Ottoman empire, suffering as it was from internal problems and dragged into the First World War, was not as effective as Russia in terms of intervention into the latter’s domestic issues. Nevertheless, there was a reality as Reynolds points out, that Ottomans were still the biggest and the strongest Muslim empire in the World. And among the biggest fears of the Tsarist Russian officials was the upheaval of Islamic waves within its territories, that they believed to be exported from Ottoman empire. This fear was not in vain…

Though the Unionists saw religion as a retrogressive and preventive force in front of the progress, they identified as Muslims and were upset from defeats of Muslims everywhere. Ottomans sent itinerant preachers to Caucasus for propagating its views among Muslims. Reynolds underlines that without the Sectarian distinction between Sunni and Shias which were crucial signifiers of identities for centuries within this region, Ottoman preachers in South Caucasus contacted all Muslims. On the other hand, the author stressed the works of Jafer Bey, the Consul of Ottomans in Tbilisi who promoted the idea that the Ottoman Sultan is the Caliph of all Muslims. These kinds of activities undertaken by Ottoman side fueled the pan-Islamism phobia within Russian empire.

Yet the Ottomans cooperated not only with Muslims and Turks in South Caucasus, but also saw Georgians, Ukrainians, Jews, and even Armenians as potential allies[6]. Not surprisingly, Unionists sent a letter titled as “To our Muslim Brothers in Caucasus” to the Caucasian Muslims with the appeal to unite against and cooperate with Armenians to defeat the mutual enemy – Russia. Both Georgian and Ukrainian Liberty legions were established with Ottomans’ support[7].

Reynolds masterfully described the contributions of both empires to one another’s collapses through the interventions to internal affairs. But there is an event in the Ottoman history that still continue repercussions on the foreign policy affairs of its successor and its analysis in Reynolds book has exclusive and controversial features.

The Russians’ double game with Armenians through their support given to Kurds against the former, and the establishment of four Armenian volunteer regiments in Russia’s army continued to confuse and raise suspicious in Ottoman side about the potential of Armenians. Ottoman fears were realized in 1915, April when the Van revolt started. Ottoman regulars and Kurdish militiamen regained the authority back from Armenians after a while. The Armenian uprising in Van brings Reynolds to the question whether it was “an act of self-defense or of treacherous collaboration[8]”?

The author presents two sides of this issue. He argues that the number of the rebels, arms and the organization form of Van revolt indicated that this uprising had been planned and arranged in advance. On the other hand, Reynolds stressed that the Van revolt was a natural consequence of a population’s fear for its security, and not simple treachery: “The natural response of any population living under such conditions of malevolent anarchy would be to arm and organize itself, and such behavior is not in itself an indication of bad faith or betrayal[9].” Indeed, the author emphasizes that cooperation with Russia at that time was simply inevitable and vital for Armenians.

Reynolds explains the relationship between Ottomans and Armenians by applying the “security dilemma” concept of International Relations, “Ottoman authorities regarded the stockpiling of arms and the organization of armed bands as an indicator of Armenian intentions to orchestrate a general uprising, while the Armenians interpreted the deployment of Ottoman forces near Van as an indicator of an intention to eliminate them[10]”. This revolt triggered deportations of Armenians.

Reynolds argues that the evaluation of one ethnic group as suspicious or deportation of them is not an unprecedented case in the history of empires. Nevertheless, the time has been changed since 19thcentury by ascending ethnicity-based issues to the salient level of determination. According to the author, the Ottomans could not keep pace with the time. Reynolds never employs the term of “genocide” in his book related to the Armenian relocation policies, but he emphasizes that these deportations comprised more radical and ambitious goals than solely security concerns.

In the later parts of the book Reynolds touches upon the developments in the South Caucasus that followed the dissolution of Tsarist Russia. Here he uses a more realistic perspective during the analysis by indicating that the Ottomans’ intrusion in the South Caucasus and Ukraine policies pertained more to the concerns of the realization of Ottoman interests rather than the willful assistance to ethnic brethren. For accentuating this point the author indicates that Ottomans were more interested in Ukraine’s fate than that of Crimean Tatars.

Nonetheless, in the last part of the book Reynolds indicates the Ottoman contribution to the independencies of the South Caucasian states that dreaded rupture with Russia even after the dissolution of the empire. The role of “Caucasian Islamic Army” for the liberation of Baku from Dashnaks and Bolsheviks, assistance given to Dagestan, the increased admiration of Turkistan to Ottoman Turks and the final defeat of Ottomans were the chronological sequence of the last chapter.

Michael Reynold’s “Shattering Empires. The Clash and Collapse of the Ottoman and Russian Empires 1908–1918” book is a comprehensive work covering a very crucial time lapse. By analyzing interrelations of two influential empires throughout minor nations living in their territories Reynolds touches upon exclusive points that orthodox history involved mostly in the fates of big nations forgets. This noticeable work illuminates detailed and contentious issues and present the readers with the historical background of some problems maintaining their importance in current days too.

© 2009-2025 Center for Eurasian Studies (AVİM) All Rights Reserved

No comments yet.

-

BOOK REVIEW: SHATTERING EMPIRES. THE CLASH AND COLLAPSE OF THE OTTOMAN AND RUSSIAN EMPIRES 1908–1918”

BOOK REVIEW: SHATTERING EMPIRES. THE CLASH AND COLLAPSE OF THE OTTOMAN AND RUSSIAN EMPIRES 1908–1918”

Nigar SHİRALİZADE 24.09.2018 -

BOOK REVIEW: AZERBAIJAN DIARY: A ROGUE REPORTER'S ADVENTURES IN AN OIL-RICH, WAR-TORN, POST-SOVIET REPUBLIC

BOOK REVIEW: AZERBAIJAN DIARY: A ROGUE REPORTER'S ADVENTURES IN AN OIL-RICH, WAR-TORN, POST-SOVIET REPUBLIC

Nigar SHİRALİZADE 20.07.2018 -

WHAT ARE THE PROSPECTS FOR ARMENIA? THE END OF “KARABAKH CLAN” OR “OLD WINE IN A NEW BOTTLE”?

WHAT ARE THE PROSPECTS FOR ARMENIA? THE END OF “KARABAKH CLAN” OR “OLD WINE IN A NEW BOTTLE”?

Nigar SHİRALİZADE 27.04.2018 -

100 YEARS OLD “YOUNG” STATES OF SOUTH CAUCASUS. LESSONS FROM AZERBAIJAN DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC

100 YEARS OLD “YOUNG” STATES OF SOUTH CAUCASUS. LESSONS FROM AZERBAIJAN DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC

Nigar SHİRALİZADE 11.06.2018

-

D.L. PHILLIPS’S DIPLOMATIC HISTORY OF THE TURKEY-ARMENIA PROTOCOLS 3

Ömer Engin LÜTEM 29.03.2012 -

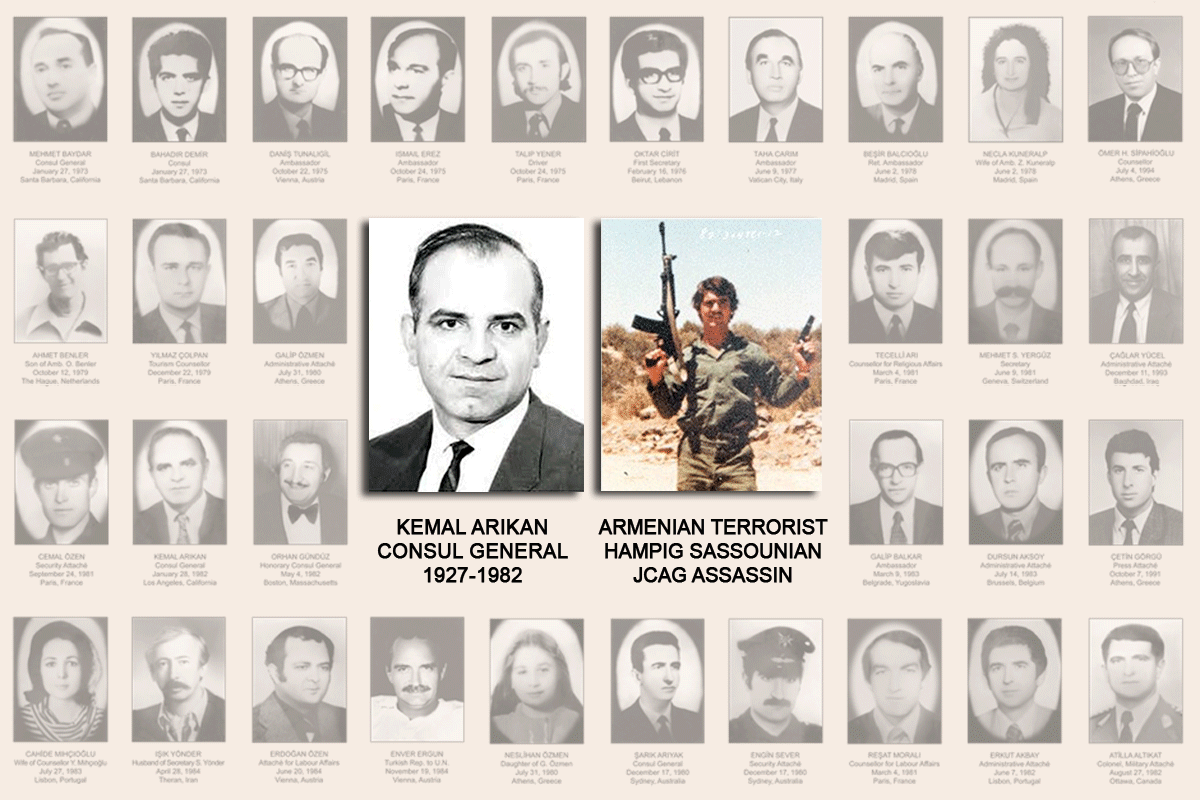

THE DECISION TO RELEASE SASSOUNIAN

THE DECISION TO RELEASE SASSOUNIAN

Hazel ÇAĞAN ELBİR 16.03.2021 -

CHAPTER BY CHAPTER SYNOPSIS AND REVIEW OF TURKS AND ARMENIANS: NATIONALISM AND CONFLICT IN THE OTTOMAN EMPIRE BY JUSTIN MCCARTHY - 5

CHAPTER BY CHAPTER SYNOPSIS AND REVIEW OF TURKS AND ARMENIANS: NATIONALISM AND CONFLICT IN THE OTTOMAN EMPIRE BY JUSTIN MCCARTHY - 5

Mehmet Oğuzhan TULUN 22.10.2015 -

ARMENIA’S NUCLEAR DILEMMA: CAUGHT BETWEEN RUSSIA AND THE WEST

ARMENIA’S NUCLEAR DILEMMA: CAUGHT BETWEEN RUSSIA AND THE WEST

Bekir Caner ŞAFAK 12.11.2025 -

THE VISA OBSTACLE FOR TURKISH CITIZENS AND THE EU'S JUSTIFICATIONS

THE VISA OBSTACLE FOR TURKISH CITIZENS AND THE EU'S JUSTIFICATIONS

Hazel ÇAĞAN ELBİR 10.10.2024

-

25.01.2016

THE ARMENIAN QUESTION - BASIC KNOWLEDGE AND DOCUMENTATION -

12.06.2024

THE TRUTH WILL OUT -

27.03.2023

RADİKAL ERMENİ UNSURLARCA GERÇEKLEŞTİRİLEN MEZALİMLER VE VANDALİZM -

17.03.2023

PATRIOTISM PERVERTED -

23.02.2023

MEN ARE LIKE THAT -

03.02.2023

BAKÜ-TİFLİS-CEYHAN BORU HATTININ YAŞANAN TARİHİ -

16.12.2022

INTERNATIONAL SCHOLARS ON THE EVENTS OF 1915 -

07.12.2022

FAKE PHOTOS AND THE ARMENIAN PROPAGANDA -

07.12.2022

ERMENİ PROPAGANDASI VE SAHTE RESİMLER -

01.01.2022

A Letter From Japan - Strategically Mum: The Silence of the Armenians -

01.01.2022

Japonya'dan Bir Mektup - Stratejik Suskunluk: Ermenilerin Sessizliği -

03.06.2020

Anastas Mikoyan: Confessions of an Armenian Bolshevik -

08.04.2020

Sovyet Sonrası Ukrayna’da Devlet, Toplum ve Siyaset - Değişen Dinamikler, Dönüşen Kimlikler -

12.06.2018

Ermeni Sorunuyla İlgili İngiliz Belgeleri (1912-1923) - British Documents on Armenian Question (1912-1923) -

02.12.2016

Turkish-Russian Academics: A Historical Study on the Caucasus -

01.07.2016

Gürcistan'daki Müslüman Topluluklar: Azınlık Hakları, Kimlik, Siyaset -

10.03.2016

Armenian Diaspora: Diaspora, State and the Imagination of the Republic of Armenia -

24.01.2016

ERMENİ SORUNU - TEMEL BİLGİ VE BELGELER (2. BASKI)

-

AVİM Conference Hall 24.01.2023

CONFERENCE TITLED “HUNGARY’S PERSPECTIVES ON THE TURKIC WORLD"