I. Introduction

This final commentary opens at a turning point for the Black Sea—one where the focus shifts from foundations and operational adjustments to the contested narratives now shaping the region’s future. Whereas earlier analyses traced the evolution of legal order and the ability of littoral actors to innovate amidst hybrid threats, today’s environment is increasingly defined by the strategic framing advanced by Russia, the West, and China. These external visions do not merely compete with interpreting events; they actively seek to mold the norms and legitimacy that will determine access, sovereignty, and maritime governance.

In this “arena of narratives,” institutional design, security alignments, and economic ambitions intersect with efforts to rewrite legal and normative boundaries. Rather than facing solely traditional risks, the Black Sea region must now navigate a shifting landscape of alternative models—each recalibrating the stakes for Turkish interests, regional balance, and the wider Eurasian order. This analysis thus critically explores how these competing discourses reflect and shape strategic realities. It asks what the contest over the Black Sea tells us about the persistent centrality of the region, and what future pathways—concrete or contested—lie ahead for Türkiye and its neighbors.

II. Competing Narratives: Russian, Western, and Chinese Frames

(A) Russian Geopolitical Perspective: Memory, Status, and Security

The Russian strategic narrative in the Black Sea is grounded in a powerful memory of imperial entitlement and the concept of a “sphere of privileged interests.” Russian state media, official documents, and think-tank commentary repeatedly frame the Black Sea as a vital space for asserting Russian power and resisting what Moscow depicts as unceasing Western encroachment. Russia posits itself as the region’s legitimate historical arbiter—direct heir to Tsarist and Soviet maritime power—while casting NATO and EU initiatives as destabilizing attempts to rewrite postwar settlement and upend local balances. This self-appointed stewardship is leveraged domestically and internationally to justify both military and non-military actions, ranging from expanded naval deployments (such as Black Sea Fleet activity and mainstreaming of "maritime peacekeeping" roles) to intensified hybrid measures including energy leverage, food shipments, and cyber activities targeting Georgia, Moldova, and Romania.[1]

One of the fundamental themes of Moscow's relations with Türkiye, particularly in the Black Sea region, has been its attempt to present the region as a pragmatic joint sphere of influence and dominance area. While such a shared vision of superiority may not please Russia, it seems possible to say that such a transition period is vital for Russia to maintain relative stability in its favor at a time when it is engaged in a heated armed conflict. In this regard, it is also possible to say that Russia's escalation of conflict while simultaneously maintaining a special status relationship with Türkiye, thus trying to limit NATO's presence without alienating the region's most important maritime partner, indicates a two-pronged approach.

In conjunction with this dual approach Russian-language outlets and their policy allies promote alternative regional security regimes, often portraying littoral-only arrangements as a check against Western intervention which, in practice, privilege Moscow's agenda.[2]

(B) Western and Chinese Models: Between Stability and Revisionism

Western narratives—driven by the EU, NATO, and the US—have increasingly converged on the Black Sea as Europe’s strategic “fulcrum.” Recent EU policy, especially the 2025 Black Sea Strategy, frames enhanced maritime governance and resilience as essential to regional and global security. Policy documents and speeches by officials like European Commission Vice-President Kaja Kallas stress the urgency of countering Russian aggression, defending open navigation, and securing undersea infrastructure, while clearly stating that Black Sea security is inseparable from Europe’s broader stability. These narratives routinely endorse collaboration with littoral states yet wrestle with the hard limits of Montreux Convention revealing contradictions between the desire to pre-empt Russian action and the structural constraints of alliance-building.[3]

NATO's recognition of the Black Sea’s centrality—while significant—remains hampered by the alliance’s difficulties in formulating a sustained, united Black Sea strategy that protects smaller coastal states and tempers the risks of escalation. Western governments also face a tactical paradox attempts to reassure Ukraine or Romania can be painted by Moscow as direct escalation, while excessive accommodation risks undermining the credibility of Western guarantees and exposing fault lines within the alliance itself.[4]

China’s presence is less overt but increasingly influential. The expansion of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) into Black Sea infrastructure and logistics reinforces Beijing’s narrative of “neutral commerce” and long-run connectivity. Chinese commentators and policy documents avoid direct security commitments, instead advocating economic multipolarity, shared investment, and the stabilization of maritime trade. Yet, Beijing’s tacit coordination with some Russian preferences, particularly in UN forums and selective project bidding, occasionally dovetails with Russian assessments of Western assertiveness as destabilizing. China’s flexible alignment signals a latent dilemma: should Chinese investment or logistical involvement grow into a demand for security arrangements, the region may face a recalibration in both Western and Russian approaches to maritime order.[5]

While Western and Chinese narratives overlap significantly in many respects in advocating multilateral frameworks and the language of stability, they diverge sharply when it comes to intervention and limits to national sovereignty. Both, in different contexts, invoke each other to justify restraint or to suggest risks of extremism.[6]

III. Sovereignty and the Limits of Accommodation: Turkish, Regional, and Normative Stakes

As evolving narratives and shifting power balances shape Black Sea strategy, Türkiye and its regional partners have sought to assert foundational priorities such as leadership, legal continuity under the Montreux Convention, and a guarded openness to adaptation that resists slipping into a condition of dependency or excessive accommodation. For Türkiye, the Convention remains non-negotiable, safeguarding regional order, prohibiting permanent non-littoral naval presence, and reinforcing the legitimacy and predictability needed by all coastal actors. By actively exercising Montreux’s controls—such as restricting Russian warship transit during the Ukraine conflict—Türkiye has demonstrated the enduring leverage provided by its legal stewardship, even as it balances NATO commitments and significant energy ties with Russia.[7]

Yet, these efforts to protect sovereignty unfold in a climate where international partners frequently test the boundaries of Turkish flexibility. EU undertakings, notably the 2025 Black Sea Maritime Security Hub, have made ambitious overtures for multilateral coordination and infrastructure protection. However, as several analysts observe, there is a persistent risk that these mechanisms overlook or marginalize the treaty-based authority and institutional prerogative of Türkiye in regulating access and scope weakening both the functional and diplomatic pillar of the regional balance.[8]

At the same time, pragmatic regional alliances—such as joint ventures in energy diversification with Azerbaijan, or the trilateral security mechanisms with Romania and Bulgaria within NATO—illustrate how Turkish policy has not ossified into rigid exclusion. Instead, Türkiye’s preference for “regional ownership” and “balancing without band wagoning” has often led it to craft inclusionary but bounded approaches, which accept cooperation contingent upon transparent alignment with sovereign legal frameworks and demonstrate notable resilience even amidst external pressures and changing security architecture.[9]

Nonetheless, the sharpest risks remain those posed by the intertwining of external strategic ambitions with ambiguous or revisionist discourses. Russian historicism and persistent promotion of an exclusive bilateral axis threaten to undermine multilateral legal continuity. Meanwhile, Western and EU rhetoric, if insufficiently attentive to Turkish legal sensitivities or operational intent, risks setting precedents that could weaken Montreux in the name of “adaptation”—potentially destabilizing the security architecture for a generation. Measured accommodation, not blanket alignment, remains Türkiye’s essential safeguard, ensuring both immediate resilience and longer-term influence over the region’s evolving order.

IV. Conclusion

The close of this Black Sea trilogy does not mark an endpoint. Rather, it underlines an evolving contest set at the crossroads of Eurasia, where the region’s inherent dynamism renders finality elusive. As this analysis has shown, the future of Black Sea security hinges not on any single initiative or foreign framework, but on the careful anchoring of traditional legal principles—embodied by the Montreux Convention—and steady adaptation to operational and narrative challenges, both external and internal. Türkiye’s role, as the historical and geographic heart of the region, remains indispensable: it acts as both a gatekeeper and a balancing actor, navigating between competing pressures while defending sovereign boundaries and continuous regional relevance.

Critically, sustaining equilibrium depends on regional actors’ ability to reinforce the spirit of multilateral cooperation, defend legal continuity, and prevent either external overreach or revisionist historical claims from upsetting the delicate maritime order. The narrative contest that animates the Black Sea—between Russia’s persistent revisionism, Western ambitions for extended order, and China’s rising commercial stake—now becomes a policy arena of its own. What emerges is a pattern in which resilience is forged less by fixed architectures than by the ongoing negotiation of sovereignty, strategic autonomy, and institutional design.

Ultimately, as the boundaries of influence and ambition shift with each new crisis and initiative, the Black Sea remains what it has always been: Eurasia’s pivotal stage for balancing coexistence, competition, and change. Here, Türkiye's leadership is defined by its ability to adjust , mediate, and sustain the region's enduring, yet always contested, heartland.

[1] Chatham House, “Understanding Russia’s Black Sea strategy,” July 28, 2025, https://www.chathamhouse.org/2025/07/understanding-russias-black-sea-strategy/01-introduction .

[2] European Parliament Think Tank, “EU strategic approach to the Black Sea region,” May 22, 2025, https://www.europarl.europa.eu/thinktank/en/document/EPRS_BRI(2025)765800 ; CEPA, “Russia's Intentions and Actions in the Black Sea,” May 30, 2025, https://www.transatlantic.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/08/RSI-II-Russia-and-the-Black-Sea-final-report-May-30-2025-final-version.pdf .

[3] RUSI, “A Strategy Long Overdue: The EU's New Vision for the Black Sea,” May 28, 2025, https://my.rusi.org/resource/a-strategy-long-overdue-the-eus-new-vision-for-the-black-sea.html ;CEPA, “Russia's Strategy and Military Thinking: Evolving Discourse by 2025,” April 24, 2025, https://cepa.org/comprehensive-reports/russias-strategy-and-military-thinking-evolving-discourse-by-2025/ .

[4] ECFR, “Bridging the Bosphorus: How Europe and Turkey can turn tiffs into tactics in the Black Sea,” March 18, 2025, https://ecfr.eu/publication/bridging-the-bosphorus-how-europe-and-turkey-can-turn-tiffs-into-tactics-in-the-black-sea/ .

[5] Sanchez VC, “The State of China's Belt and Road Initiative (August 2025),” August 21, 2025, https://www.sanchez.vc/geocoded-special-reports/the-state-of-chinas-belt-and-road-initiative-august-2025 .

[6] Green Finance & Development Center (Fudan), “China Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) investment report 2025 H1,” July 17, 2025, https://greenfdc.org/china-belt-and-road-initiative-bri-investment-report-2025-h1/ .

[7] Atlantic Council, “Exploring cooperation between Turkey and the West in the Black Sea,” October 6, 2024, https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/A-Sea-of-Opportunities-L_2.pdf.

[8] TRT World Research Centre, “A Littoral Solution: Türkiye’s Role in a Safer Black Sea,” September 11, 2025, https://researchcentre.trtworld.com/publications/analysis/a-littoral-solution-turkiyes-role-in-a-safer-black-sea/.

[9] OSW Commentary, “Romania, Bulgaria and Turkey in the Black Sea region,” June 26, 2025, https://www.osw.waw.pl/en/publikacje/osw-commentary/2025-06-26/romania-bulgaria-and-turkey-black-sea-region-increased

© 2009-2025 Center for Eurasian Studies (AVİM) All Rights Reserved

No comments yet.

-

ESTABLISHING THE DELICATE BALANCE BETWEEN STRATEGIC AUTONOMY AND STRATEGIC INTERDEPENDENCE: THE CASE OF TÜRKIYE

ESTABLISHING THE DELICATE BALANCE BETWEEN STRATEGIC AUTONOMY AND STRATEGIC INTERDEPENDENCE: THE CASE OF TÜRKIYE

Teoman Ertuğrul TULUN 05.08.2025 -

1934 PACT OF BALKAN ENTENTE: THE PRECURSOR OF BALKAN/SOUTHEAST EUROPE COOPERATION

1934 PACT OF BALKAN ENTENTE: THE PRECURSOR OF BALKAN/SOUTHEAST EUROPE COOPERATION

Teoman Ertuğrul TULUN 06.08.2020 -

ATTACK ON THESSALONIKI MAYOR: PONTIAN GREEK HATE SPEECH TURNS INTO HATE CRIMES

ATTACK ON THESSALONIKI MAYOR: PONTIAN GREEK HATE SPEECH TURNS INTO HATE CRIMES

Teoman Ertuğrul TULUN 30.05.2018 -

A MISNOMER: WESTERN BALKANS

A MISNOMER: WESTERN BALKANS

Teoman Ertuğrul TULUN 10.07.2017 -

2025 MUNICH SECURITY CONFERENCE AND THE NECESSITY OF CONSTRUCTIVE EURASIANISM

2025 MUNICH SECURITY CONFERENCE AND THE NECESSITY OF CONSTRUCTIVE EURASIANISM

Teoman Ertuğrul TULUN 28.02.2025

-

AT THE CROSSROADS: TÜRKİYE AND THE BATTLE FOR BLACK SEA ORDER

AT THE CROSSROADS: TÜRKİYE AND THE BATTLE FOR BLACK SEA ORDER

Teoman Ertuğrul TULUN 21.10.2025 -

THE LEGAL STATUS OF THE FENER GREEK PATRIARCHATE

THE LEGAL STATUS OF THE FENER GREEK PATRIARCHATE

Gözde KILIÇ YAŞIN 19.10.2022 -

BLACK SEA NEEDS CONFIDENCE AND SECURITY BUILDING MEASURES MORE THAN EVER

BLACK SEA NEEDS CONFIDENCE AND SECURITY BUILDING MEASURES MORE THAN EVER

Teoman Ertuğrul TULUN 30.10.2018 -

HIGHLIGHTS FROM THE US PRESIDENT TRUMP’S ASIA TRIP

HIGHLIGHTS FROM THE US PRESIDENT TRUMP’S ASIA TRIP

Seyda Nur OSMANLI 29.01.2026 -

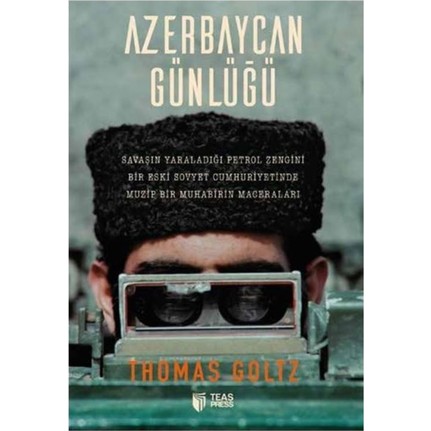

BOOK REVIEW: AZERBAIJAN DIARY: A ROGUE REPORTER'S ADVENTURES IN AN OIL-RICH, WAR-TORN, POST-SOVIET REPUBLIC

BOOK REVIEW: AZERBAIJAN DIARY: A ROGUE REPORTER'S ADVENTURES IN AN OIL-RICH, WAR-TORN, POST-SOVIET REPUBLIC

Nigar SHİRALİZADE 20.07.2018

-

25.01.2016

THE ARMENIAN QUESTION - BASIC KNOWLEDGE AND DOCUMENTATION -

12.06.2024

THE TRUTH WILL OUT -

27.03.2023

RADİKAL ERMENİ UNSURLARCA GERÇEKLEŞTİRİLEN MEZALİMLER VE VANDALİZM -

17.03.2023

PATRIOTISM PERVERTED -

23.02.2023

MEN ARE LIKE THAT -

03.02.2023

BAKÜ-TİFLİS-CEYHAN BORU HATTININ YAŞANAN TARİHİ -

16.12.2022

INTERNATIONAL SCHOLARS ON THE EVENTS OF 1915 -

07.12.2022

FAKE PHOTOS AND THE ARMENIAN PROPAGANDA -

07.12.2022

ERMENİ PROPAGANDASI VE SAHTE RESİMLER -

01.01.2022

A Letter From Japan - Strategically Mum: The Silence of the Armenians -

01.01.2022

Japonya'dan Bir Mektup - Stratejik Suskunluk: Ermenilerin Sessizliği -

03.06.2020

Anastas Mikoyan: Confessions of an Armenian Bolshevik -

08.04.2020

Sovyet Sonrası Ukrayna’da Devlet, Toplum ve Siyaset - Değişen Dinamikler, Dönüşen Kimlikler -

12.06.2018

Ermeni Sorunuyla İlgili İngiliz Belgeleri (1912-1923) - British Documents on Armenian Question (1912-1923) -

02.12.2016

Turkish-Russian Academics: A Historical Study on the Caucasus -

01.07.2016

Gürcistan'daki Müslüman Topluluklar: Azınlık Hakları, Kimlik, Siyaset -

10.03.2016

Armenian Diaspora: Diaspora, State and the Imagination of the Republic of Armenia -

24.01.2016

ERMENİ SORUNU - TEMEL BİLGİ VE BELGELER (2. BASKI)

-

AVİM Conference Hall 24.01.2023

CONFERENCE TITLED “HUNGARY’S PERSPECTIVES ON THE TURKIC WORLD"