Aysel Nur GENÇ

Traineeship Program Participant

Abstract: The EU's Strategic Autonomy Initiative, often referred to in the context of US-EU relations, is important for understanding EU-China relations. The Russia-Ukraine conflict has underlined the necessity and challenges of the EU's strategic autonomy. China, which wants to increase its global influence, has been making discourses in support of the EU's initiative. The study focuses on the scope of the EU's strategic autonomy initiatives and the question of whether the EU's strategic autonomy initiative will lead to complete independence as a global actor or to a closer alignment with China. The report analyses China-EU relations within the framework of economy, technology and climate change.

--------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Introduction

The debate on the 'Strategic Autonomy' of the European Union (EU) is gaining importance as global economic, political, and security dynamics change. Although some member states anticipate that strategic autonomy would weaken transatlantic connections and national sovereignty, the term has played an essential role in comprehending the EU's position in a changing geopolitical environment.

There is ongoing discussion about where the European Union stands regarding its strategic autonomy objectives and how this goal will evolve. As it currently stands, the term refers to strengthening the EU's ability to become more integrated within the Union while remaining independent of the United States on strategic issues. The EU's defense dependence on the United States has become a hot topic, especially after Russia's aggression against Ukraine.[1] Proponents of ‘Strategic Autonomy’ initiatives suggest that the EU should take joint decisions on defence against the Russian threat.

While analyzing the EU's strategic autonomy ambitions, it is crucial to consider the EU's ties with the US and its relations with China. The EU sees China as “a partner for co-operation, an economic competitor and a systemic challenge.”[2] However, EU-China connections are getting more multifaceted and controversial, affected by various causes, including the Ukraine-Russia war, the European Union's green transformation ambitions, China's worldwide economic influence, and technological progress.

Despite the considerable amount of data on EU-China relationship dynamics in the literature, there are different interpretations. The EU-China network, which is constantly evolving and covers a wide range of fields, can mean different things to various EU member states and, at times, pose risks to the EU. The Russia-Ukraine war has shifted the EU's energy and security policies, influenced by China's pro-Russian stance. The EU wants China to use its influence over Russia to contribute to ending the war. [3]

While most people refer to strategic autonomy as independence from the US, it also includes acting as a global actor without being dependent on any global powers, such as China. This study will focus on whether the ‘Strategic Autonomy’ initiative will only make the region more independent from the US and bring it closer to China, the other global power, rather than making the European Union a global power. EU-China relations will be analyzed in the context of the economy, technology, and the climate crisis, focusing on whether the EU can be an independent actor from the US and China or whether it has to choose between the two global powers.

1. European Union’s Strategic Autonomy

In the wake of global crises, the idea of strategic autonomy in the European Union has received significant attention. However, there is still debate over the definition of this concept. In order to make sense of the concept, we need to analyze the EU's norms, historical background, and its relations with other global actors. Additionally, understanding the concept of 'autonomy'—often confused with sovereignty'—and distinguishing between autonomy and strategic autonomy is essential. This helps to comprehend where the EU positions itself internationally within the framework of strategic autonomy initiatives and to interpret its relations with China, a global actor with increasing influence. [4]

The Greek word 'autonomos,' derived from 'autos' (self) + 'nomos' (law), is where the term 'autonomy' originates, meaning 'having its own laws'. The term 'autonomy' signifies 'the right or condition of self-government' and 'freedom from external control or influence; independence'. However, 'autonomy' does not equate to strategic autonomy.[5]

Although there are discussions about a more integrated Europe, similar to Churchill's idea of a 'United States of Europe,' [6] the EU's efforts to achieve strategic autonomy in defense while defining its identity through multilateralism do not imply that it can currently take steps that would harm partnerships like the UN and NATO.

Despite China's pro-Russian stance in the Russia-Ukraine war, its increasing economic power, and its attempts to reshape the international order by shifting the balance of power to Asia, EU-China relations continue to develop, especially in strategic areas. The EU, which strives to be independent from the US, especially in the field of defense, has realized that rising Russian threats make this difficult without collaborating with China on climate change, technology, and trade. At this point, the EU, which aims to be strategically autonomous, is dependent on China in many areas that are considered crucial for strategic autonomy. China is aware of this strategic dependence, despite Xi Jinping's rhetoric expressing support for strategic autonomy.[7]

The EU's attempts at establishing strategic autonomy have been unspecific and ambiguous. The EU needs strategic autonomy to support its rhetoric of rights and democracy and to enhance its institutional power. In addition, the US disengagement from regions such as the Balkans, the Middle East, North Africa, and Eastern Europe has created a power gap. The interests of the actors filling the power gap, namely Russia and Turkiye, are in conflict with those of the EU. [8] The EU's administrative deficiencies and the slow decision-making process cause it to fail in its intervention strategy. In this context, strategic autonomy initiatives aim to accelerate the process by becoming more integrated and removing the veto right in important areas such as foreign policy and security.

Macron has repeatedly voiced the strategic autonomy initiative, which appears to have gained momentum after Brexit. This initiative envisions integration not only in defense and foreign policies but also in the economy. Nevertheless, there are actors, such as Denmark, who are trying to keep EU-UK relations intact after Brexit in order not to disrupt transatlantic ties and avoid difficulties in defense.[9] However, as evidenced by the rise of right-wing parties in the European Parliament elections, the number of eurosceptics is not insignificant. These conflicts and incompatibilities between EU member states change the dynamics of relations in favor of China. This has led to a decline in the relative influence of European governments in Beijing. These inconsistencies and relationship instability also make it difficult for them to pursue a specific strategic policy.[10]

In general, the EU pursues a policy of bureaucracy and soft power. Therefore, in the military and defense fields, it had no choice but to adapt to US interests in neighboring regions. The EU does not have an integrated and effective military organization. In addition to their military underdevelopment, common interests and strong transatlantic ties with the US have also been obstacles to strategic autonomy. Just as the EU needs to develop its relations with China for its economy, technology, and climate efforts, it also needs to maintain a balanced relationship with the US for security. The EU must maintain this balance in the coming years. However, the changing world order makes the region's relations with China, as well as the ‘Strategic Autonomy’ initiatives, uncertain.[11]

2. EU – China Trade Relations

China's global economic rise is changing international balances. Europe, too, is entering a new chapter as it seeks to become an actor in the global order. In this changing context, Europe-China relations are becoming more complex and, at the same time, more important for the EU.

The ongoing war between Russia and Ukraine, as well as the COVID-19 pandemic, have emphasized Europe's need for strategic autonomy and economic stability. This includes lowering their critical reliance on China, particularly in terms of economic and national security.[12]

These global changes have complicated both strategic autonomy initiatives and inter-actor relations. Moreover, deep trade ties with China and competition among EU member states to attract investment from China complicate the pursuit of strategic autonomy initiatives in the economic context.[13]

Foreign policy also reflects the impact of the strategic autonomy initiatives on the economy. Seeking independence from the US, the EU's relations with China are also developing at the member state-China level.

In the last five years, China has significantly increased its investment activity, particularly in Central, Eastern and Southern Europe.[14] This has resulted in a growth in economic ties and dependencies, which, combined with Beijing's assertive diplomatic approach, has led to the establishment of Beijing-controlled relations. [15]

EU member states, especially in Central and Eastern Europe, see improving economic relations with China as a crucial step for economic growth. Many EU member states are in a dilemma between EU norms such as democracy and human rights and China-backed economic growth.

Democracy and human rights continue to be key considerations in shaping relations with China. Josep Borrell, the High Representative of the European Commission for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy, criticized China's policies towards the Uyghur Turkic Muslims in Xinjiang in a 2020 speech to the European Parliament. He pointed to the establishment of re-education centers for the Uyghurs and the suppression of their right to preserve their tradition and practice their religion.[16]

In December 2020, the European Union officially implemented the Global Human Rights Sanction Regime. This regime empowers the EU to impose sanctions on states that engage in human rights violations. [17]

While these ideals have sometimes harmed ties with Beijing, they may also be challenged by economic considerations. Furthermore, not all EU member states consistently support initiatives in this field.

If the EU wants to proceed beyond its strategic autonomy ambitions, it must move beyond rhetoric and take concrete steps to accomplish its autonomous development goals, mainly in the economy. Trade links and reliance on China undermine the notion of strategic autonomy, but changing member states' interests and skepticism about the EU's strategic autonomy may reshape relations with China.

Decoupling aims to lessen reliance on China as a protective measure against potential economic or geopolitical challenges. Conversely, de-risking, similar to decoupling, aims to sustain essential trade and investment activities after risk mitigation. Research indicates that doubling trade barriers would lead to a 97% decrease in trade between the EU and China. Under this scenario, the EU would reclaim some production and divert the remaining imports to other countries, thereby virtually ending trade with China. In the long run, this total decoupling has the potential to permanently cut the EU's real revenue by 0.8%, resulting in an annual loss of €136 billion. The loss would be 0.9% for China. These economic results make it clear why full de-coupling is not a practical option.

The EU is taking action to ensure industrial sovereignty, such as the Raw Materials Act and the Net-Zero Industry Act. [18] However, these actions are not enough to ensure industrial sovereignty and move production to Europe. Long-term, it will lead to continued dependence on China for key raw materials such as silicon and lithium.[19]

In order to reduce its reliance on China, the EU is seeking to diversify its sources of strategic raw materials. Reducing trade costs and negotiating free trade agreements with other supplier states may help to expedite this process. For instance, agreements with countries such as Malaysia and Australia may enhance the EU's access to resources outside China. Furthermore, agreements like EU-Mercosur, which provide access to these resources, could also speed up the process. On the other hand, the European Union (EU) terminated its trade pact negotiations with Australia in October 2023 and suspended its negotiations with Malaysia for several years.[20]

.jpg)

Vasileios Rizos, Edoardo Righetti, and Amin Kassab, "Developing a Supply Chain for Recycled Rare Earth Permanent Magnets in the EU: Challenges and Opportunities," CEPS In-Depth Analysis, December 2022.

China's share of EU exports has been declining since reaching a high of 10.5% in 2020. This drop may represent China's lowered expenditure because of factors such as its zero-Covid plan. Between 2014 and 2022, the EU's imports from China climbed considerably. Imports were EUR 627 billion in 2022, decreasing to EUR 515 billion in 2023. China is the top source country for EU imports, accounting for 20.5%, ahead of the United States (13.8%) and the United Kingdom (7.1%). However, beginning in 2021, China's contribution decreased as imports from other areas increased more rapidly. This might reflect a trend toward lowering the EU's reliance on China. [21]

.png)

Alexander Sandkamp, EU-China Trade Relations: Where Do We Stand, Where Should We Go? Kiel Policy Brief no. 176 (Kiel Institute for the World Economy, May 2024),

Understanding the dynamics of China-EU relations on infrastructure and technology, as well as on solutions to the climate crisis, necessitates an interpretation of trade relations in general. There are many ways in which the EU depends on China for its economic resilience. And the Sino-EU relationship does not do justice to the meaning of the words ‘Strategic Autonomy’. Despite the pro-European approaches of France and Germany, the cornerstone countries of the EU, their trade relations with China show that a complete decoupling will not be possible despite all efforts. In addition, there is a widespread view in EU public opinion that dependence on China and its economic relations do not pose a risk to Europe.[22] It once again raises questions about the scope of the strategic autonomy discourse.

3. European Digital Sovereignty and China

The concept of European digital sovereignty is directly relevant to strategic autonomy initiatives, as it has the potential to impact not only foreign companies operating within the EU but also any citizen of the world.[23] For the European Union, the concept of digital sovereignty is not only a tool for expanding influence and ensuring strategic autonomy but also a concept with social implications, such as protecting the privacy of individuals.[24] The EU also highlights technology and digital transformation as crucial steps toward sustainability, trust, and democracy.[25]

While China sees digitalisation as a means of national power [26], the EU sees it as an aspect that should be safe and can contribute to the development of social and democratic values and society. On human rights and political freedoms, there are major differences between Europe and China's discourse. On privacy protection and security, Europe and the U.S. have similar views but sometimes take different actions.

China is quickly advancing in the technology race with the US, making significant progress in a short time. [27] The EU is attempting to ensure its digital autonomy to balance China and the US, but China, which plays an active role in areas such as artificial intelligence, 5G technologies, and digital infrastructure, is increasing its competitiveness day by day.

The European Parliament envisaged various strategies to cope with this competition. For instance, the European Parliament emphasized priority areas like bolstering digital infrastructure, enhancing cyber security, and enhancing data protection policies in its briefing 'Digital Sovereignty for Europe'.[28]

Artificial Intelligence (AI)

As AI advances, its importance in international relations continues to grow. China, which considers artificial intelligence to be both technological and multifaceted, has announced its goal of becoming a global center for artificial intelligence innovation by 2030, maintaining its assertiveness in this field. [29] The Chinese government's broad data mining powers are mutually reinforcing in direct proportion to advances in artificial intelligence. [30]

In response, the European Parliament has called for international negotiations to ban automated weapon systems. Furthermore, Parliament resolutions have called for sanctions against Chinese authorities and state-led organizations for their digital surveillance and severe repression of fundamental rights. The Parliament also established a special committee on artificial intelligence in the digital age and conducted a study on ‘Artificial Intelligence Diplomacy’.[31]

The EU attaches importance to ethical and safety standards in artificial intelligence. The European Commission emphasizes the concept of ethical and trustworthy[32] AI and argues that AI should be transparent, accountable, and respectful of human rights. [33] However, China's rapid progress and large investments in AI make Europe dependent on China for access to these technologies.

5G and Telecommunication

The EU's 5G policy is a critical aspect of its technological independence and global influence. Initiatives in 5G and telecommunications provide important insights into how the EU's strategic autonomy will evolve between the US and China. 5G technology is critical for keeping pace with digitalization and economic growth. As a result, the EU seeks to be independent while maintaining cooperation in this field as well as in many other areas.

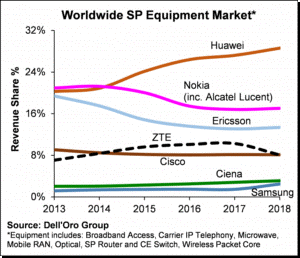

Huawei Technologies—a company with far-reaching effects on technology—took the lead among providers of telecommunications equipment, surpassing American Cisco, Swedish Ericsson, Finnish Nokia, South Korean Samsung, and ZTE Corporation at 2018.[34]

Stefan Pongratz, "Key Takeaways – Worldwide Telecom Equipment Market 2018," Dell’Oro Group, May 20, 2019.

The US has adopted laws that prohibit the use of Chinese Huawei and ZTE products, as well as contracts with organizations that use these products. Stating that it took this decision due to national security concerns, the US also pressured its allies on this issue. [35] The US encouraged allied countries such as Japan, the UK, and Canada, which follow a US-oriented policy, to pursue a policy against Chinese infrastructure companies on the basis of security measures.[36] The EU, one of the United States’ allies, published the ‘EU Toolbox for 5G Security’, which is not binding for member countries but basically expresses the risks.[37] With the US pressure and increasing tension after Russia's invasion of Ukraine, the perspective of the EU, which does not follow very harsh policies due to economic and technological interests, has changed. In 2023, Germany, which resisted imposing sanctions on Huawi due to its economic advantages, began to investigate Huawei.[38] As an actor in favour of strategic autonomy as well as being the engine of the EU, Germany's stance in the China-EU relationship raises many questions about the EU's place in the global arena.

Conflicting Interests In Central Asia

Central Asia presents significant opportunities for both China and the EU to invest in digital infrastructure. [39]. While the EU continues to collaborate with countries in the region through the Global Gateway initiative,[40] China engages in the region through the Belt and Road Project. Although China, known for its rapid and extensive investments, has various advantages, both aim to increase their global effectiveness by implementing their own agendas. While the EU aims to achieve technological autonomy, China is moving towards technological leadership.

China's geographical advantage in the Eurasian region also has an impact in Central Asia. [41]China's BRI and Digital Silk Road initiatives, which are part of China's rapid and extensive investments rather than the EU's sustainability and human rights rhetoric, have attracted more attention in Central Asia. Huawei is a major provider of communication networks in Kyrgyzstan, supplying 80 percent of the country's networks. Additionally, they are responsible for supplying 90 percent of the hardware for Sky Mobile and 70 percent for Alfa Telecom, two leading telecom companies. Furthermore, Chinese technology companies have provided funding and oversight for Bishkek's digital security network, incorporating advanced technologies like facial recognition cameras and 5G networks. [42]

China's advantage lies in its investment capacity, while the EU tries to close the gap by developing more sustainable and green data centers and prioritizing security and human rights. While China finances projects such as railways and digital networks as part of large-scale investments, the EU's investments are more long-term. The EU intends to raise €300 billion for global infrastructure projects by 2027. [43] The initial budget for digital connectivity in Central Asia is €40 million.[44]

To achieve full strategic autonomy, the EU must also be technologically autonomous. However, a lack of technological investments and cooperation makes it impossible to compete with an actor such as China and obtain digital sovereignty.

4. Climate Change and Energy

The climate crisis and energy security are among the most debated issues in the international arena and in society. Some argue that states are using the climate crisis as a propaganda tool to manipulate societies, not just for economic gains. This leads to ongoing debates about the definition of the climate crisis, appropriate actions, and the extent of the danger.

China is responsible for 35 per cent of the world's carbon emissions. [45] However, as a party to the Paris agreement, China has a target to reduce its carbon emissions to zero by 2060.[46] In addition, the EU, like China, is a party to the Paris Agreement and has announced its goal of neutralising carbon emissions by 2050 as part of the ‘Green Deal’. These initiatives, as well as the UN's 'Climate Neutral Now' initiative, have brought the climate crisis to the field of industry and technology, accelerating it.[47]

Europe's Green Deal has significant potential to shape strategic autonomy initiatives and the EU's position in the international context. The EU projects that restrictions on fossil fuels will incentivize the transition to domestic renewable energies, which account for 12% of EU GDP. By achieving carbon-neutral ambitions, the EU aims to reduce fossil fuel imports and reduce dependence on Russia, a perceived geopolitical threat.[48]

MEPs in the European Parliament, particularly the 'far right' parties, have criticized the EU's plan to lead the fight against the climate crisis through legislative reforms within the Union as part of its commitment to a sustainable Europe. These critiques stem not only from the potential negative impact of the Green Deal on the economy and industrial competition, but also from the perception that the Green Deal is a step towards strategic autonomy, which envisions a more integrated EU. This is because the EU, through the Green Deal, not only aims to become a global leader in sustainability but has also emerged as a viable solution to its existential crises and a path towards Europeanism as a supraidentity, a topic widely discussed under the umbrella of strategic autonomy initiatives.[49]

When the EU prioritizes economic and energy security with its green transformation goals, it aims to become a global leader by considering regulatory values. China, on the other hand, has viewed green transformation primarily as a tool for domestic development, but these developments have elevated China to a leadership position in this field. [50]

Previously, China argued that the rich countries should bear the responsibility for the climate crisis. However, since the start of Xi Jinping's presidential term, China has drastically changed its rhetoric, joining international initiatives to address the climate crisis and promoting cooperation.[51]

China is implementing numerous measures to lessen its reliance on fossil fuels, particularly coal, which many favor due to their increased security, affordability, and profitability. In order to reduce dependence on fossil fuels, China has established a capacity equivalent to the solar capacity of all other countries in the world and doubled its additional solar capacity in 2023.[52] In addition, China has suspended the plans to build new coal-fired power plants abroad as part of its climate change initiatives. Within these initiatives, China is building the world's most efficient clean energy generation system. [53] Analysis of China's and the EU's green transformation targets reveals a priority for win-win cooperation. However, serious differences in production share and production capacities lead to question marks.

China is globally dominant in solar energy technology with 80% production capacity.[54] China, which manufactures on a large scale while keeping costs low, is considered as an important actor to fulfill the EU's green transformation targets such as increasing solar energy to 600 gigawatts by 2030. In addition, Chinese companies supply 90 per cent of solar photovoltaic modules in the EU.[55] The EU, whose production share is decreasing, is becoming dependent on Chinese imports in an area of strategic importance, such as green transformation.

On the other hand, the European Commission initiated an investigation targeting the Chinese companies LONGi Solar and Shanghai Electric Group, bidders in the construction of a 110 megawatt photovoltaic park in Romania, partially financed with EU funds, on the claim that the use of state subsidies by Chinese solar panel manufacturers creates unfair competition in the EU market.[56] However, there are also actors who believe that import restrictions will hinder Europe's green transformation and negatively affect the win-win cooperation relations with China.

The EU, which is heavily dependent on China in the sustainable energy sector, also faces major risks in the electric vehicles and battery industry. [57] Although supply chain dependence is believed to speed up the green transformation, it significantly undermines energy security, also a crucial aspect of strategic autonomy initiatives.

In October 2023, EU Commission President Ursula Von der Leyen announced the launch of an investigation to restrict Chinese imports of battery electric vehicles (BEVs) and the implementation of equalization taxes starting July 4, 2024. [58] While some view this as a boost to national security and the EU BEV market, others argue that it could impede the green transformation process and hinder strategic autonomy initiatives. The EU, relies on China for electric vehicle batteries and solar panels, like many other strategic industries, and its future direction remains uncertain.

The EU and China pursue cooperative and harmonised policies in many areas such as post-pandemic green recovery. China acknowledges the EU's pioneering role in low-carbon development, characterizing it as a “stabiliser”, and believes that collaboration will lead to the attainment of these objectives. [59]

Conclusion

The European Union’s Strategic Autonomy Initiatives affect not only the EU's internal dynamics but also its relations with international actors. Despite ongoing debates about its scope, feasibility, and impact, a thorough analysis of the EU's norms and historical background is necessary to comprehend these discussions.

The concept of the EU as a federative union goes much further than strategic autonomy. However, some actors within the EU, such as ‘far-right’ parties in the European Parliament, argue that the Strategic Autonomy initiative would give the union a federative status and that more integrated decision-making by the union is a threat to the national decision-making bodies of the member states.

Strategic autonomy goals imply the continent's self-sufficiency in matters of strategic importance and independence from the United States, particularly in terms of defense. Furthermore, the Russia-Ukraine war demonstrated the EU's inadequacy in defense alone. Europe, which should pursue a balanced strategy for regional security, shows different tendencies in different areas of its relations with China.

Without China's contribution, achieving the goal of an integrated EU with economic stability, enhanced technological capacity, and global leadership in the battle against climate change is considered a difficult task. The EU's difficulties in taking coordinated decisions have led to uncertainty in relations with China across the Union, creating a network that at times works in China's favor.

The European Union aims for economic independence as part of its strategic autonomy initiatives. According to research findings, implementing stricter trade barriers would result in a significant 97% decline in trade volume between the European Union and China. In this particular scenario, the European Union would regain control over certain production processes and redirect the remaining imports to alternative countries, effectively bringing trade with China to a halt. Over time, the decoupling strategy could have a lasting impact on the EU's actual income, reducing it by 0.8% and leading to an annual deficit of €136 billion. In addition, China would experience a 0.9% loss. The European Union is taking various initiatives to reduce dependence on China in critical domains, but it seems that a complete decoupling is not viable.

The EU has aimed to progress in many areas, from combating climate change to improving the effectiveness of the union. At the same time, taking into account the effects of technology and digitalization on society, the EU aims for safe technology and continues its human rights discourse in the field of technology. Due to a lack of strict security standards, China is making large-scale and rapid investments and approaching its technological development leadership targets. The US sanctions on Chinese companies under security measures have adversely impacted the EU's relationship with China, which has also boosted its investments in the EU's technology and infrastructure sectors. This situation, in addition to the EU's dependence on China on strategic issues, shows that the EU is unable to take initiative independently from its ally, the US, on strategic issues that are important in establishing its own prospects. Due to its strong transatlantic ties, US policies and sanctions impact the EU's relations with third countries and organizations.

Climate change plays a major role in EU-China relations. The two actors, who have different priorities in green transformation as well as technological transformation, have found common ground by becoming parties to the Paris agreement and participating in carbon emission reduction projects. However, within the scope of strategic autonomy initiatives, the EU, which aims for global leadership in the battle against the climate crisis, is heavily dependent on China, especially in important areas such as solar panels, wind turbines, and electric vehicle batteries. China, recognizing the EU's sustainability leadership goals, has become the global leader due to its large production capacity. Despite the emphasis on a win-win relationship, the EU's insufficient production capacities and China's large-scale production capacity make the situation challenging. In particular, dependence on electric vehicles and the battery industry could jeopardize energy security. Therefore, the EU will restrict imports of battery electric vehicles from China and plans to reduce this dependency by imposing equalization taxes. However, these steps may also potentially stall the green transformation process.

In conclusion, the re-emergence of the strategic autonomy discourse has shifted the focus to the multifaceted China-EU relations. Competition and incompatible policies among the EU member states have made relations with China uncertain, which has put Beijing in an advantageous position. However, it is challenging for the EU, attempting to lessen its reliance on the US, to achieve its objectives in areas such as economic sustainability, technological advancement, and climate crisis management without a strong foundation in its relations with China. This creates a dichotomy between being an independent actor and being independent from the US, demonstrating that the current scope of strategic autonomy is to pursue a policy of balance among global powers rather than to participate in the international arena as a global actor.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Alcidi, Cinzia, Tamas Kiss-Gálfalvi, Doina Postica, Edoardo Righetti, Vasileios Rizos, and Farzaneh Shamsfakh. What Ways and Means for a Real Strategic Autonomy of the

EU in the Economic Field? Final report. Study for the European Economic and Social Committee. CEPS - Centre for European Policy Studies, November 10, 2023.

doi:10.2864/552201

Altun, Sirma, and Ceren Ergenc. "The EU and China in the Global Climate Regime: A Dialectical Collaboration-Competition Relationship." Asia Europe Journal 21, no. 3 (2023): 437-457.

“Autonomy.” n.d. In Bab.La. https://en.bab.la/dictionary/english/autonomy.

Bongardt, A., and F. Torres. The Political Economy of Europe’s Future and Identity: Integration in Crisis Mode. European University Institute, 2023. https://data.europa.eu/doi/10

Brattberg, Erik, Philippe Le Corre, Paul Stronski, and Thomas De Waal. 2021. “China’s Influence in Southeastern, Central, and Eastern Europe: Vulnerabilities and Resilience in Four Countries.” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. October 2021. https://carnegieendowment.org/research/2021/10/chinas-influence-in-southeastern-central-and-eastern-europe-vulnerabilities-and-resilience-in-four-countries?lang=en.

Cheng, Christina. 2023. “Is The EU Finally Headed Towards a Ban on Huawei?” Chinaobservers. September 7, 2023. https://chinaobservers.eu/is-the-eu-finally-headed-towards-a-ban-on-huawei/.

“China : Artificial Intelligence at the Heart of the Chinese Government.” 2018. IGPDE. Responsive Public Management. https://www.economie.gouv.fr/files/files/directions_services/igpde-editions-publications/revuesGestionPublique/IGPDE-reactive_Chine_EN.pdf.

“Commission Imposes Provisional Countervailing Duties on Imports of Battery Electric Vehicles From China While Discussions With China Continue.” 2024. European Commission. July 2024. https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_24_3630.

“Commission Opens Two In-depth Investigations Under the Foreign Subsidies Regulation in the Solar Photovoltaic Sector.” 2024. European Commission. April 2024. https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/IP_24_1803.

Dempsey, Judy. 2023. “Judy Asks: Is European Strategic Autonomy Over?” Carnegie Europe. January 2023. https://carnegieendowment.org/europe/strategic-europe/2023/01/judy-asks-is-european-strategic-autonomy-over?lang=en¢er=europe.

di Carlo, Ivano. "EU–China relations at a crossroads, Vol. III: Business Unusual” Europe in the World Programme 29 (2024).

EEAS. 2023. “EU-China Relations Factsheet.” The Diplomatic Service of the European Union. Accessed July 8, 2024. https://www.eeas.europa.eu/sites/default/files/documents/2023/EU-China_Factsheet_Dec2023_02.pdf.

“Ethics Guidelines for Trustworthy AI.” 2019. Shaping Europe’s Digital Future. April 8, 2019. https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/library/ethics-guidelines-trustworthy-ai.

“EU CHINA RELATIONS.” 2023. EEAS. https://www.eeas.europa.eu/sites/default/files/documents/2023/EU-China_Factsheet_Dec2023_02.pdf.

“EU-CHINA COOPERATION ON GREEN RECOVERY AND GREEN STIMULUS: An Overview of Green Recovery Measures in the EU & Their Implications for EU-China Relations.” 2020. European Commission Climate Action. European Commission. https://climate.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2021-06/eu_chn_paper_green_recovery_20201019_en.pdf.

Euronews. 2022. “ABD, Çinli Teknoloji Şirketlerinin Ürünlerinin Satışını Yasakladı.” Euronews, November 26, 2022. https://tr.euronews.com/2022/11/26/abd-cinli-teknoloji-sirketlerinin-urunlerinin-satisini-yasakladi.

European Commission. 2021. “Winston Churchill: Calling for a United States of Europe.” Accessed July 7, 2024. https://european-union.europa.eu/principles-countries-history/history-eu/eu-pioneers/winston-churchill_en.

European Commission. White Paper on Artificial Intelligence: A European Approach to Excellence and Trust. Brussels: European Commission, 2020. https://ec.europa.eu/info/files/white-paper-artificial-intelligence-european-approach-excellence-and-trust_en.

FRANKE, Ulrike. 2021. “Artificial Intelligence Diplomacy: Artificial Intelligence Governance as a New European Union External Policy Tool.” European Parliament. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2021/662926/IPOL_STU(2021)662926_EN.pdf.

“Global Gateway: EU and Central Asian Countries Agree on Building Blocks to Develop the Trans-Caspian Transport Corridor.” 2024. Directorate General for International Partnerships. January 30, 2024. https://international-partnerships.ec.europa.eu/news-and-events/news/global-gateway-eu-and-central-asian-countries-agree-building-blocks-develop-trans-caspian-transport-2024-01-30_en.

Gundal, Andrew, and Eldaniz Gusseinov. 2024. “Competing Digital Futures: Europe and China in Central Asia’s Tech Development.” The Diplomat, May 23, 2024. https://thediplomat.com/2024/05/competing-digital-futures-europe-and-china-in-central-asias-tech-development/.

Hilton, Isabel. 2024. “How China Became the World’s Leader on Renewable Energy.” Yale E360. March 2024. https://e360.yale.edu/features/china-renewable-energy#:~:text=China%20still%20generates%20about%2070,use%20lags%20behind%20installed%20capacity.

Huotari, Mikko, Miguel Otero-Iglesias, John Seaman, and Alice Ekman, eds. 2015. “Mapping Europe-China Relations: a Bottom-Up Approach.” IFRI. https://www.ifri.org/sites/default/files/atoms/files/etnc_web_final_1-1.pdf.

Joyce, Gu Bin. 2024. “Understanding China’s Changing Climate Change Rhetoric.” East Asia Forum. April 2024. https://eastasiaforum.org/2024/04/05/understanding-chinas-changing-climate-change-rhetoric/.

Karpathiotaki, Pelagia, Yunhua Tian, Yanping Zhou, and Xiaohao Huang. “China’s Belt and Road Initiative: Contributions to Connectivity.” In New Dimensions of Connectivity in the Asia-Pacific, edited by CHRISTOPHER FINDLAY and SOMKIAT TANGKITVANICH, 1st ed., 41–90. ANU Press, 2021. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctv23hcdsw.10

Kimball, Emilie, Rush Doshi, Ryan Hass, and Tarun Chhabra. 2020. “Global China: Technology.” Brookings, April 2020. https://www.brookings.edu/articles/global-china-technology/.

Lee-Makiyama, Hosuk. “The EU Green Deal and Its Industrial and Political Significance.” European Centre for International Political Economy, 2021. http://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep29234.

Lipke, Alexander, Janka Oertel, and Daniel O’Sullivan. 2024. “Trust and Trade-offs: How to Manage Europe’s Green Technology Dependence on China.” ECFR. May 2024. https://ecfr.eu/publication/trust-and-trade-offs-how-to-manage-europes-green-technology-dependence-on-china/#:~:text=In%20Europe%2C%20Chinese%20firms%20provide,of%20the%20world's%20polysilicon%20supply.

Madiega, Tambiama. 2020. “Digital Sovereignty for Europe.” EPRS | European Parliamentary Research Service. European Parliament. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/BRIE/2020/651992/EPRS_BRI(2020)651992_EN.pdf.

Mazzocco, Ilaria. 2023. “Balancing Act: Managing European Dependencies on China for Climate Technologies.” https://www.csis.org/analysis/balancing-act-managing-european-dependencies-china-climate-technologies.

Moens, Barbara. 2023. “EU Lines up 70 Projects to Rival China’S Belt and Road Infrastructure Spending.” POLITICO, January 25, 2023. https://www.politico.eu/article/eu-sets-outs-projects-to-make-global-gateway-visible-on-the-ground/.

Nissen, Christine, Cecilie Felicia Stokholm Banke, Jakob Linnet Schmidt, Mikkel Runge Olesen, Hans Mouritzen, Jon Rahbek-Clemmensen, Rasmus Brun Pedersen, Graham Butler, and Louise Riis Andersen. “FUTURE PROSPECTS.” EUROPEAN DEFENCE COOPERATION AND THE DANISH DEFENCE OPT-OUT: Report on the Developments in the EU and Europe in the Field of Security and Defence Policy and Their Implications for Denmark. Danish Institute for International Studies, 2020. http://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep25193.12

Pacheco, Marta. 2024. “China Dominating Soaring Global Clean Tech Industry.” Euronews,

Pollet, Mathieu, and John Hendel. 2023. “The West Is on a World Tour Against Huawei.” POLITICO, November 28, 2023. https://www.politico.eu/article/west-world-tour-huawei-china-telecom/.

Pongratz, Stefan. 2019. “Key Takeaways – Worldwide Telecom Equipment Market 2018.” Dell’Oro Group. May 20, 2019. https://www.delloro.com/telecom-equipment-market-2018-2/.

Puglierin, Jana, and Pavel Zerka. 2023. “Keeping America Close, Russia Down, and China Far Away: How Europeans Navigate a Competitive World.” ECFR. June 8, 2023. https://ecfr.eu/publication/keeping-america-close-russia-down-and-china-far-away-how-europeans-navigate-a-competitive-world/.

Pohle, Julia, and Thorsten Thiel. 2020. "Digital sovereignty". Internet Policy Review 9 (4). DOI: 10.14763/2020.4.1532. https://policyreview.info/concepts/digital-sovereignty

Sandkamp, Alexander. EU-China Trade Relations: Where Do We Stand, Where Should We Go? Kiel Policy Brief no. 176. Kiel Institute for the World Economy, May 2024. https://www.ifw-kiel.de/fileadmin/Dateiverwaltung/IfW-Publications/fis-import/f9a2be87-5855-42b5-bb52-79656914e0f8-KPB176.pdf

“Shaping Europe’s Digital Future.” 2020. European Commission. European Union. https://doi.org/10.2759/091014.

Shen, Olivia. “AI DREAMS AND AUTHORITARIAN NIGHTMARES.” In China Dreams, edited by Jane Golley, Linda Jaivin, Ben Hillman, and Sharon Strange, 142–56. ANU Press, 2020. http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctv12sdxmk.17

Szczudlik, Justyna. 2024. “Why the EU Must Keep Talking with China about Russia.” Chinaobservers, May 2024. https://chinaobservers.eu/why-the-eu-must-keep-talking-with-china-about-russia/#:~:text=Von%20der%20Leyen%20and%20Michel,to%20Russia%20and%20circumventing%20sanctions.

“The Changing Landscape of Global Emissions – CO2 Emissions in 2023 – Analysis - IEA.” n.d. IEA. https://www.iea.org/reports/co2-emissions-in-2023/the-changing-landscape-of-global-emissions#:~:text=China%20alone%20accounts%20for%2035,average%2C%20at%20around%202%20tonnes.

“The EU Toolbox for 5G Security.” 2020. Shaping Europe’s Digital Future. January 29, 2020. https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/library/eu-toolbox-5g-security.

Tocci, Nathalie. 2021. “European Strategic Autonomy: What It Is, Why We Need It, How to Achieve It.” IAI - Istituto Affari Internazionali. 2021. Accessed June 8, 2024. https://www.iai.it/sites/default/files/9788893681780.pdf.

Torres Pérez, Maria. 2022. “The European Union Protection of Human Rights through Its Global Policy: The Implementation of the Regime of Restrictive Measures Against Serious Violations and Abuses of Human Rights”. The Age of Human Rights Journal, no. 19 (December): 255-69. https://doi.org/10.17561/tahrj.v19.7071.

Yang, Na. "How China Perceives European Strategic Autonomy: Asymmetric Expectations and Pragmatic Engagement." The Chinese Journal of International Politics 16, no. 4 (Winter 2023): 482–505. https://doi.org/10.1093/cjip/poad014.

“WRI China.” n.d. World Resources Institute. https://www.wri.org/asia/wri-china.

“Xinjiang: Speech by High Representative/Vice-President Josep Borrell at the EP Debate on the Human Rights Situation.” n.d. EEAS. https://www.eeas.europa.eu/eeas/xinjiang-speech-high-representativevice-president-josep-borrell-ep-debate-human-rights-situation_en.

单学英. n.d. “China Policy Key to EU’s Strategic Autonomy.” Opinion - Chinadaily.Com.Cn. https://www.chinadaily.com.cn/a/202306/19/WS648f9103a31033ad3f7bceb0.html.

[1] Judy Dempsey, "Judy Asks: Is European Strategic Autonomy Over?" Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, January 19, 2023, https://carnegieendowment.org/europe/strategic-europe/2023/01/judy-asks-is-european-strategic-autonomy-over?lang=en¢er=europe.

[2] European External Action Service, "EU China Relations," December 2023, https://www.eeas.europa.eu/sites/default/files/documents/2023/EU-China_Factsheet_Dec2023_02.pdf.

[3] Justyna Szczudlik, "Why the EU Must Keep Talking with China about Russia," China Observers, May 21, 2024, https://chinaobservers.eu/why-the-eu-must-keep-talking-with-china-about-russia/.

[4] Nathalie Tocci, European Strategic Autonomy: What It Is, Why We Need It, How to Achieve It (Rome: Istituto Affari Internazionali, 2021), https://www.iai.it/sites/default/files/9788893681780.pdf.

[5] "Autonomy," n.d., in Bab.La, https://en.bab.la/dictionary/english/autonomy.

[6] European Commission, "Winston Churchill: Calling for a United States of Europe," in EU Pioneers, https://european-union.europa.eu/system/files/2021-06/eu-pioneers-winston-churchill_en.pdf.

[7] Na Yang, "How China Perceives European Strategic Autonomy: Asymmetric Expectations and Pragmatic Engagement," The Chinese Journal of International Politics 16, no. 4 (Winter 2023): 483, https://doi.org/10.1093/cjip/poad014.

[8] Tocci, European Strategic Autonomy.

[9] Christine Nissen et al., "Future Prospects," in European Defence Cooperation and the Danish Defence Opt-Out: Report on the Developments in the EU and Europe in the Field of Security and Defence Policy and Their Implications for Denmark (Copenhagen: Danish Institute for International Studies, 2020): 66 https://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep25193.12.

[10] Mikko Huotari, Miguel Otero-Iglesias, John Seaman, and Alice Ekman, eds., Mapping Europe-China Relations: A Bottom-Up Approach. A Report by the European Think-tank Network on China (ETNC), October 2015: 5 https://www.ifri.org/sites/default/files/atoms/files/etnc_web_final_1-1.pdf.

[11] 单学英. n.d. “China Policy Key to EU’s Strategic Autonomy.” Opinion - Chinadaily.Com.Cn. https://www.chinadaily.com.cn/a/202306/19/WS648f9103a31033ad3f7bceb0.html.

[12] Alicia García-Herrero, The EU’s Concept of De-Risking Hovers Around Economic Diversification Rather Than National Security (Bruegel, December 6, 2023), 15, https://www.bruegel.org/sites/default/files/2024-07/The%20EU’s%20concept%20of%20de-risking%20hovers%20around%20economic%20diversification%20rather%20than%20national%20security.pdf.

[13] Huotari et al., Mapping Europe-China Relations. 13.

[14] Erik Brattberg, Philippe Le Corre, Paul Stronski, and Thomas de Waal, "China’s Influence in Southeastern, Central, and Eastern Europe: Vulnerabilities and Resilience in Four Countries," Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, October 13, 2021, https://carnegieendowment.org/research/2021/10/chinas-influence-in-southeastern-central-and-eastern-europe-vulnerabilities-and-resilience-in-four-countries?lang=en.

[15] Huotari et al., Mapping Europe-China Relations. 5.

[16] Borrell, Josep. "Speech by High Representative/Vice-President Josep Borrell at the EP Debate on the Human Rights Situation in Xinjiang." European External Action Service, December 17, 2020. Accessed July 23, 2024. https://www.eeas.europa.eu/eeas/xinjiang-speech-high-representativevice-president-josep-borrell-ep-debate-human-rights_en.

[17] Maria Torres Pérez, “The European Union Protection of Human Rights through Its Global Policy: The Implementation of the Regime of Restrictive Measures Against Serious Violations and Abuses of Human Rights,” The Age of Human Rights Journal 19 (December 2022): 257, https://doi.org/10.17561/tahrj.v19.7071.

[18] García-Herrero, "The EU’s Concept of De-Risking." 21.

[19] Cinzia Alcidi et al., What Ways and Means for a Real Strategic Autonomy of the EU in the Economic Field? (CEPS - Centre for European Policy Studies, November 10, 2023), doi:10.2864/552201.

[20] Sandkamp, "EU-China Trade Relations," 10.

[21] Sandkamp, "EU-China Trade Relations," 5.

[22] Jana Puglierin and Pawel Zerka, "Keeping America Close, Russia Down, and China Far Away: How Europeans Navigate a Competitive World," policy brief, European Council on Foreign Relations, June 7, 2023, 7, https://ecfr.eu/publication/keeping-america-close-russia-down-and-china-far-away-how-europeans-navigate-a-competitive-world/#china-is-not-russia.

[23] Andrea Bongardt and Francisco Torres, The Political Economy of Europe’s Future and Identity: Integration in Crisis Mode (Florence: European University Institute, 2023): 288, https://doi.org/10.2870/383521.

[24] Julia Pohle and Thorsten Thiel, “Digital Sovereignty,” Internet Policy Review 9, no. 4 (2020): 2, https://doi.org/10.14763/2020.4.1532; https://policyreview.info/concepts/digital-sovereignty.

[25] European Commission, Shaping Europe’s Digital Future (Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union, 2020), https://commission.europa.eu/system/files/2020-02/communication-shaping-europes-digital-future-feb2020_en_4.pdf.

[26] Tarun Chhabra, Rush Doshi, Ryan Hass, and Emilie Kimball, "Global China: Technology," Brookings Institution, April 2020: 1, https://www.brookings.edu/articles/global-china-technology/.

[27] Chhabra et al., "Global China: Technology." :2

[28] European Parliament. (2020). Digital sovereignty for Europe.: 4, https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/BRIE/2020/651992/EPRS_BRI(2020)651992_EN.pdf

[29] Ministry for the Economy and Finance of France, China: Artificial Intelligence at the Heart of the Chinese Government, Responsive Public Management No. 105 (September 2018):1, https://www.economie.gouv.fr/files/files/directions_services/igpde-editions-publications/revuesGestionPublique/IGPDE-reactive_Chine_EN.pdf.

[30] Shen, Olivia. “AI DREAMS AND AUTHORITARIAN NIGHTMARES.” In China Dreams, edited by Jane Golley, Linda Jaivin, Ben Hillman, and Sharon Strange, 142–56. ANU Press, 2020: 150,

[31] European Parliament, Artificial Intelligence Diplomacy: Artificial Intelligence Governance as a New European Union External Policy (June 2021). https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2021/662926/IPOL_STU(2021)662926_EN.pdf.

[32] European Commission, White Paper on Artificial Intelligence: A European Approach to Excellence and Trust, COM(2020) (Brussels, 19 February 2020): 25 https://commission.europa.eu/document/download/d2ec4039-c5be-423a-81ef-b9e44e79825b_en?filename=commission-white-paper-artificial-intelligence-feb2020_en.pdf

[33] High-Level Expert Group on Artificial Intelligence, Ethics Guidelines for Trustworthy AI, set up by the European Commission, April 2019: 23, https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/library/ethics-guidelines-trustworthy-ai.

[34] Stefan Pongratz, "Key Takeaways – Worldwide Telecom Equipment Market 2018," Dell’Oro Group, May 20, 2019, https://www.delloro.com/telecom-equipment-market-2018-2/.

[35] "ABD Çinli Teknoloji Şirketlerinin Ürünlerinin Satışını Yasakladı," Euronews, November 26, 2022, https://tr.euronews.com/2022/11/26/abd-cinli-teknoloji-sirketlerinin-urunlerinin-satisini-yasakladi.

[36] Mathieu Pollet and John Hendel, "The West Is on a World Tour Against Huawei," Politico, November 28, 2023, https://www.politico.eu/article/west-world-tour-huawei-china-telecom/.

[37] European Commission, EU Toolbox for 5G Security: A Set of Robust and Comprehensive Measures for an EU Coordinated Approach to Secure 5G Networks, January 29, 2020, https://digital-strategy.ec.europa.eu/en/library/eu-toolbox-5g-security.

[38] Christina Cheng, "Is the EU Finally Headed Towards a Ban on Huawei?," China Observers in Central Asia, September 7, 2023, https://chinaobservers.eu/is-the-eu-finally-headed-towards-a-ban-on-huawei/.

[39] Moens, Barbara. "EU Lines Up 70 Projects to Rival China’s Belt and Road Infrastructure Spending." Politico, January 23, 2023. https://www.politico.eu/article/eu-sets-outs-projects-to-make-global-gateway-visible-on-the-ground/.

[40] European Commission, "Global Gateway: EU and Central Asian Countries Agree on Building Blocks to Develop the Trans-Caspian Transport Corridor," January 30, 2024, https://international-partnerships.ec.europa.eu/news-and-events/news/global-gateway-eu-and-central-asian-countries-agree-building-blocks-develop-trans-caspian-transport-2024-01-30_en.

[41] Pelagia Karpathiotaki, Yunhua Tian, Yanping Zhou, and Xiaohao Huang, "China’s Belt and Road Initiative: Contributions to Connectivity," in New Dimensions of Connectivity in the Asia-Pacific, ed. Christopher Findlay and Somkiat Tangkitvanich (Canberra: ANU Press, 2021), https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctv23hcdsw.10.

[42] Andrew Gundal and Eldaniz Gusseinov, "Competing Digital Futures: Europe and China in Central Asia’s Tech Development," The Diplomat, May 23, 2024, https://thediplomat.com/2024/05/competing-digital-futures-europe-and-china-in-central-asias-tech-development/.

[43]European Commission, “Global Gateway.”

[44] Gundal and Gusseinov, "Competing Digital Futures."

[45] International Energy Agency (IEA), “The Changing Landscape of Global Emissions – CO2 Emissions in 2023 – Analysis,” n.d., https://www.iea.org/reports/co2-emissions-in-2023/the-changing-landscape-of-global-emissions#:~:text=China%20alone%20accounts%20for%2035,average%2C%20at%20around%202%20tonnes.

[46] World Resources Institute, “WRI China,” n.d., https://www.wri.org/asia/wri-china.

[47]Ivano di Carlo, "EU–China Relations at a Crossroads, Vol. III: Business Unusual," Europe in the World Programme 29 (2024): 50

[48] Hosuk Lee-Makiyama, “The EU Green Deal and Its Industrial and Political Significance,” European Centre

for International Political Economy, 2021, 8, http://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep29234.

[49] Lee-Makiyama, “The EU Green Deal and Its Industrial and Political Significance,” 4.

[50] Sirma Altun and Ceren Ergenc, "The EU and China in the Global Climate Regime: A Dialectical Collaboration-Competition Relationship," Asia Europe Journal 21, no. 3 (2023): 453.

[51] Gu Bin Joyce, “Understanding China’s Changing Climate Change Rhetoric,” East Asia Forum, April 2024, https://eastasiaforum.org/2024/04/05/understanding-chinas-changing-climate-change-rhetoric/.

[52] Isabel Hilton, “How China Became the World’s Leader on Renewable Energy,” Yale E360, March 2024, https://e360.yale.edu/features/china-renewable-energy#:~:text=China%20still%20generates%20about%2070,use%20lags%20behind%20installed%20capacity.

[53]di Carlo, EU–China Relations at a Crossroads, 65.

[54] Marta Pacheco, “China Dominating Soaring Global Clean Tech Industry,” Euronews, May 6, 2024, https://www.euronews.com/green/2024/05/06/china-dominating-soaring-global-clean-tech-industry#:~:text=China%20houses%20more%20than%2080,of%20total%20exports%20in%202023.

[55] Alexander Lipke, Janka Oertel, and Daniel O’Sullivan, “Trust and Trade-offs: How to Manage Europe’s Green Technology Dependence on China,” European Council on Foreign Relations (ECFR), May 2024, https://ecfr.eu/publication/trust-and-trade-offs-how-to-manage-europes-green-technology-dependence-on-china/#:~:text=In%20Europe%2C%20Chinese%20firms%20provide,of%20the%20world's%20polysilicon%20supply.

[56] “Commission Opens Two In-depth Investigations Under the Foreign Subsidies Regulation in the Solar Photovoltaic Sector,” European Commission, April 2024, https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/IP_24_1803.

[57] Ilaria Mazzocco, “Balancing Act: Managing European Dependencies on China for Climate Technologies,” Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS), 2023, https://www.csis.org/analysis/balancing-act-managing-european-dependencies-china-climate-technologies.

[58] “Commission Imposes Provisional Countervailing Duties on Imports of Battery Electric Vehicles From China While Discussions With China Continue,” European Commission, July 2024, https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/ip_24_3630.

[59] “EU-China Cooperation on Green Recovery and Green Stimulus: An Overview of Green Recovery Measures in the EU & Their Implications for EU-China Relations,” European Commission Climate Action, European Commission, 2020, 39, https://climate.ec.europa.eu/system/files/2021-06/eu_chn_paper_green_recovery_20201019_en.pdf.

© 2009-2025 Center for Eurasian Studies (AVİM) All Rights Reserved

AVİM’de tüm yıl boyunca Uygulamalı Eğitim Programı (UEP) devam etmektedir. Avrasya bölgesine dair çalışmalara ilgi duyan adaylar, bu programa kısa veya uzun dönemli katılımlar için başvuruda bulunabilirler.

Bu sayfada AVİM Uygulamalı Eğitim Programı katılımcılarının hazırlamış oldukları raporlardan bazı örnekler yayınlanmaktadır. Yayınlanan raporlar yalnızca yazarlarının görüşlerini temsil etmektedir ve bu raporların AVİM için bağlayıcılığı bulunmamaktadır.

The Traineeship Program at AVİM is offered throughout the year. Applicants are expected to possess a high interest in Eurasian affairs. Applications for the program may be made either for the short or the long term.

Some examples of the reports prepared by Traineeship Program participants are published on this page. These reports solely reflect the views of their authors and are not binding for AVİM.