A video recently emerged online, where retired Armenian Colonel Gilbert Levon Minassian, interviewed by a Georgian blogger, Tako Tamuna, confesses without shame his role in the massacre of Khojaly (February 1992):

- You were in Khojaly, too?

- Yes, Khojaly is my business. The Azerbaijanis are looking for me. I cannot count how many times I have stabbed [killed]. It is like that, my dear [this is how things work, dear].

This confession is reminiscent of the interview where Serzh Sargsyan, commander of the Armenian invading troops in 1992, later President of Armenia (2008-2018), stated:

“Before Khojaly the Azerbaijanis thought that they were joking with us, they thought that the Armenians were people who could not raise their hand against the civilian population. We needed to put a stop to all that. And that’s what happened.”[1]

The Soviet 366th regiment, made of Russian Armenians, was among the main perpetrators of the massacre.[2] Human Rights Watch reported: “Armenian forces killed unarmed civilians and soldiers who were hors de combat, and looted and sometimes burned homes.”[3] The same organization published a partial list of the victims.[4] Foreign journalists observed that at least three of the killed inhabitants of Khojaly had been scalped.[5] The Azerbaijani authorities identified 613 killed civilians, including 106 women and 63 children.

The trajectory of Gilbert Levon Minassian, this self-described criminal against humanity, needs to be recalled. At the end of 1970s, he was a member of the Union of Communist Students. Around 1980, he joined the “political” wing of the (pro-Soviet[6]) “Armenian Secret Army for the Liberation of Armenia” (ASALA) in France, named “Armenian Liberation” then “Armenian National Movement” (MNA) for the ASALA. The MNA served as a cover for the logistical network of the ASALA,[7] for the exfiltration of the perpetrators of the ASALA’s attacks,[8] and, according to the Turkish diplomacy, for designating to the terrorists their targets.[9] In August 1983, the MNA sided with Monte Melkonian in the ASALA split. Minassian made the same choice and became a member of the MNA’s political bureau.

Regardless, the split did not stop the funding of the lawyers’ costs of arrested ASALA terrorists by the MNA and did not even discourage this group from contributing to the ASALA propaganda. Indeed, Minassian, speaking on behalf of the MNA, attributed the bombing of the headquarters of “Armenian Youth of France” (controlled by the Hunchak Party) in Marseille, on 17 March 1984, to a “Fascist organization controlled by the Turkish government.”[10] In truth, this bombing, like all the other attacks against Armenian associations in France in 1981 and 1984, were false flag actions by the ASALA, as proved by documents seized in Monte Melkonian’s cache in 1985 and read during his trial in 1986.[11]

On 28 July 1984, Minassian took part in the attack of a postal van, aimed to fund the activities of the MNA. Arrested on 2 August of the same year and indicted, he escaped and left France on 28 July 1987. He was sentenced in absentia to life-long imprisonment in 1989.[12] He fled to Greece, then to Yugoslavia. These choices are not surprising. Greece supported Armenian terrorism until the assassination of ASALA leader Hagop Hagopian in Athens, in 1988.[13] Yugoslavia arrested the two assassins of Turkish ambassador Galip Balkar in Belgrade, Harutyun Levonian and Raffi Elbakian (members of the “Armenian Revolutionary Federation”), in March 1983, and sentenced them to twenty years in jail in March 1984, but, in the second half of 1980s, the most aggressive of kind of Serbian nationalism, incarnated by Slobodan Milosevic, started replacing the softened Communism that had prevailed since 1948. Levonian was released, officially for medical reasons, in June 1987, one month before Minassian’s escape. Milosevic, as President of Yugoslavia, pardoned Elbekian in 1990.[14]

Meanwhile, Monte Melkonian had been sentenced to six years in jail (including two suspended), a fine and a permanent ban from the French territory after his release, for illegal possession of weapons, of explosives, and of fake ID documents. On 10 January 1989, the decision to release Melkonian and to expel him to the United States (where he faced a longer sentence) was announced. Melkonian’s lawyers appealed this decision. Minassian went to a telephone cabin, called the headquarters of the Le Parisien newspaper, and threatened to perpetrate bloody bombings in France if Melkonian was extradited to the US, adding that he did not care about his own fate, having been sentenced to life-long imprisonment. Melkonian was eventually expelled to South Yemen[15] (a Communist state, which collapsed in 1990 and merged with the North Yemen). Like his friend Minassian, Melkonian went to Armenia in 1990 and became an officer of the Armenian army, taking part to the invasion of Karabakh and to the expulsions of Azerbaijani civilians. He was killed in action by Azerbaijani soldiers in 1993.[16] In the context of the collapse of the Communist bloc in Eastern Europe, from June 1989 to January 1990, and of intensification of the repression of the Armenian terrorism against the Turks (Sassounian trials in 1984 and 1986, trial of the Orly bombing in 1985, trial of the assault against the Turkish embassy in Ottawa in 1986, all concluded by sentences to life-long imprisonment), Azerbaijan, weakened by seven decades of Soviet occupation, was an easier target than the Turkish diplomatic missions and the Western airports.

Taking profit of the limitation statute and of an error of law committed by the Ministry of Justice in 2004, Gilbert Levon Minassian went back to France, but never asked for a revision of his sentence of 1989. He returned to Armenia in 2020, in order to fight the Azerbaijanis again. That is why the Azerbaijani embassy filed a complaint against him in December 2020.[17] As his recently emerged video indicates, Minassian seems to harbour no remorse for the cruelty and violence he has committed in the past, which demonstrates the dangerous and corrupting influence of extremist ideologies.

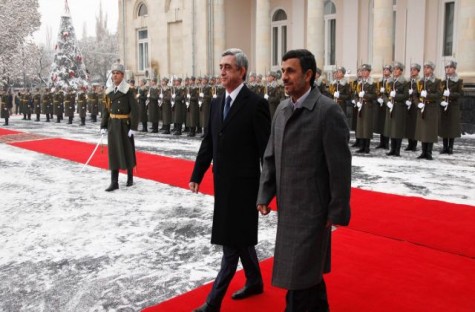

*Image: Gilbert Levon Minassian – Source: Valentine Vermeil, Le Journal du Dimanche (JDD)

[1] Thomas de Waal, Black Garden. Armenia and Azerbaijan Through Peace and War, New York-London: New York University Press, 2013, pp. 184-185.

[2] Ibid., p. 183.

[3] https://www.hrw.org/reports/1993/WR93/Hsw-07.htm. Also see Response to Armenian Government Letter on the town of Khojaly, Nagorno-Karabakh, 23 March 1997, https://www.hrw.org/news/1997/03/23/response-armenian-government-letter-town-khojaly-nagorno-karabakh

[4] Bloodshed in the Caucasus. Escalation of the Armed Conflict in Nagorno-Karabakh, 1992, pp. 55-61.

[5] « Alors que les combats s'intensifient — M. Bush réclame un cessez-le-feu au Karabakh — Agdam, ville fantôme », Le Monde, 14 mars 1992, https://www.lemonde.fr/archives/article/1992/03/14/alors-que-les-combats-s-intensifient-m-bush-reclame-un-cessez-le-feu-au-karabakh-agdam-ville-fantome_3877060_1819218.html

[6] Armand Gaspard (Gasparian), Le Combat arménien, Lausanne : L’Âge d’homme, 1984, p. 71

[7] The network was dismantled in July 1982 and all the members, sentenced in 1985, were also members of the MNA: Richard Mels, “30 mois avec sursis pour Charles Sansonetti et Katchadur Gulumian”, Hay Baykar, 25 November 1985, p. 5. The ASALA established a second network at the end of 1982, dismantled after the Orly bombing. All the members, one more time, were also members of the MNA: “Cinq complices dans l’attentat d’Orly sont condamnés à des peines de prison”, Le Monde, 24 décembre 1984, https://www.lemonde.fr/archives/article/1984/12/24/cinq-complices-dans-l-attentat-d-orly-sont-condamnes-a-des-peines-de-prison_3022429_1819218.html This trial was, with the trial of Orly bombing properly speaking, the most painful for the Armenian nationalists in France: “Procès des boucs émissaires de la répression anti-arménienne à Créteil”, Hay Baykar, 12 janvier 1985, pp. 4-8.

[8] “Bobigny : la solidarité arménienne condamnée”, Hay Baykar, 10 May, 1985, pp. 8-9.

[9] Tunç Üğdül, Diplomasi Cephesi. Hariciyeci Bir Çiftin 40 Yılı (1980-2020), İstanbul: Remzi Kitabevi, 2022, pp. 38-39.

[10] “Les auteurs de l'attentat de Marseille ont pris le risque de tuer”, Le Monde, 20 March 1984, https://www.lemonde.fr/archives/article/1984/03/20/les-auteurs-de-l-attentat-de-marseille-ont-pris-le-risque-de-tuer_3015806_1819218.html

[11] Laurent Greilsamer, “Les archives sanglantes du terrorisme arménien“, Le Monde, 1 December 1986, https://www.lemonde.fr/archives/article/1986/12/01/les-archives-sanglantes-du-terrorisme-armenien_2931870_1819218.html

[12] “À Aix-en-Provence — Mandat d’arrêt contre un responsable du Mouvement national arménien”, Le Monde, 30 July 1987, https://www.lemonde.fr/archives/article/1987/07/30/a-aix-en-provence-mandat-d-arret-contre-un-responsable-du-mouvement-national-armenien_4045379_1819218.html ; Aziz Zemouri, “Une plainte en France contre les ‘combattants français’ du Haut-Karabakh”, Lepoint.fr, 29 December 2020, https://www.lepoint.fr/societe/une-plainte-en-france-contre-les-combattants-francais-du-haut-karabakh-29-12-2020-2407381_23.php

[13] Gaïdz Minassian, Guerre et terrorisme arméniens, Paris, Presses universitaires de France, 2002, pp. 44, 83, 105 and 125.

[14] Bilâl N. Şimşir, Şehit Diplomatlarımız (1973-1994), Ankara-İstanbul, Bilgi Yayınevi, 2000, vol. II, pp. 687-689.

[15] Markar Melkonian, My Brother’s Road. An American Fateful Journey to Armenia, London-New York: I. B. Tauris, 2007, pp. 166-167.

[16] Ibid., passim.

[17] Aziz Zemouri, “Une plainte en France contre les ‘combattants français’ du Haut-Karabakh”, Lepoint.fr, 29 décembre 2020, https://www.lepoint.fr/societe/une-plainte-en-france-contre-les-combattants-francais-du-haut-karabakh-29-12-2020-2407381_23.php

© 2009-2025 Center for Eurasian Studies (AVİM) All Rights Reserved

No comments yet.

-

PROMINENT SUPPORTER OF ARMENIAN LOBBIES IN FRANCE SENTENCED FOR CORRUPTION

PROMINENT SUPPORTER OF ARMENIAN LOBBIES IN FRANCE SENTENCED FOR CORRUPTION

Maxime GAUIN 22.10.2015 -

WHAT KIND OF “RECONCILIATION” IS THE HRANT-DINK FOUNDATION PROMOTING?

WHAT KIND OF “RECONCILIATION” IS THE HRANT-DINK FOUNDATION PROMOTING?

Maxime GAUIN 19.03.2015 -

THE ARCHIVES OF THE ARF-DASHNAK REMAIN CLOSED

THE ARCHIVES OF THE ARF-DASHNAK REMAIN CLOSED

Maxime GAUIN 28.06.2019 -

WHO IS RESPONSIBLE FOR THE CLOSING OF TURKISH-ARMENIAN BORDER?

WHO IS RESPONSIBLE FOR THE CLOSING OF TURKISH-ARMENIAN BORDER?

Maxime GAUIN 04.02.2015 -

BAKU TO THE FUTURE: AZERBAIJAN, NOT ARMENIA, IS ISRAEL'S TRUE ALLY

BAKU TO THE FUTURE: AZERBAIJAN, NOT ARMENIA, IS ISRAEL'S TRUE ALLY

Maxime GAUIN 10.11.2014

-

TANER AKÇAM AND AGOS DO NOT SURPISE US ANYMORE

TANER AKÇAM AND AGOS DO NOT SURPISE US ANYMORE

Turgut Kerem TUNCEL 08.05.2017 -

BOOK LAUNCH - “AZA BEAST - ATTACKING THE ROOTS OF WAR”

AVİM 21.10.2013 -

THE ORGANIZATION OF TURKIC STATES AND THE CLAIMS OF TURANISM AND PANTURKISM

THE ORGANIZATION OF TURKIC STATES AND THE CLAIMS OF TURANISM AND PANTURKISM

Selenay Erva YALÇIN 19.12.2024 -

IRAN AND SHANGHAI COOPERATION ORGANIZATION

IRAN AND SHANGHAI COOPERATION ORGANIZATION

Özge Nur ÖĞÜTCÜ 27.06.2016 -

TENSION OVER THE LACHIN CORRIDOR BETWEEN AZERBAIJAN AND ARMENIA

TENSION OVER THE LACHIN CORRIDOR BETWEEN AZERBAIJAN AND ARMENIA

AVİM 11.08.2023

-

25.01.2016

THE ARMENIAN QUESTION - BASIC KNOWLEDGE AND DOCUMENTATION -

12.06.2024

THE TRUTH WILL OUT -

27.03.2023

RADİKAL ERMENİ UNSURLARCA GERÇEKLEŞTİRİLEN MEZALİMLER VE VANDALİZM -

17.03.2023

PATRIOTISM PERVERTED -

23.02.2023

MEN ARE LIKE THAT -

03.02.2023

BAKÜ-TİFLİS-CEYHAN BORU HATTININ YAŞANAN TARİHİ -

16.12.2022

INTERNATIONAL SCHOLARS ON THE EVENTS OF 1915 -

07.12.2022

FAKE PHOTOS AND THE ARMENIAN PROPAGANDA -

07.12.2022

ERMENİ PROPAGANDASI VE SAHTE RESİMLER -

01.01.2022

A Letter From Japan - Strategically Mum: The Silence of the Armenians -

01.01.2022

Japonya'dan Bir Mektup - Stratejik Suskunluk: Ermenilerin Sessizliği -

03.06.2020

Anastas Mikoyan: Confessions of an Armenian Bolshevik -

08.04.2020

Sovyet Sonrası Ukrayna’da Devlet, Toplum ve Siyaset - Değişen Dinamikler, Dönüşen Kimlikler -

12.06.2018

Ermeni Sorunuyla İlgili İngiliz Belgeleri (1912-1923) - British Documents on Armenian Question (1912-1923) -

02.12.2016

Turkish-Russian Academics: A Historical Study on the Caucasus -

01.07.2016

Gürcistan'daki Müslüman Topluluklar: Azınlık Hakları, Kimlik, Siyaset -

10.03.2016

Armenian Diaspora: Diaspora, State and the Imagination of the Republic of Armenia -

24.01.2016

ERMENİ SORUNU - TEMEL BİLGİ VE BELGELER (2. BASKI)

-

AVİM Conference Hall 24.01.2023

CONFERENCE TITLED “HUNGARY’S PERSPECTIVES ON THE TURKIC WORLD"