EU Observer (9 March 2018)

Or as much of it as I could find, anyway, as in truth, it is often far from clear where one jurisdiction begins and the other one ends.

Starting in Donegal and finishing in Louth, in the Cooley mountains, it was during this ad hoc trip that the gravity of the situation finally sank in.

Up until then I had considered the issue of the border to be being overplayed, both by the Irish, and by British 'Remainers' desperate to find any means of halting Brexit.

These towns and villages from my youth, such as Pettigo, riven by the frontier, and Omeath, where my family sought respite from dull and depressing grind of the Northern conflict, would once again be subject, at the very least, to customs checks, and surely most of the estimated 275 now unguarded open border crossings would once again be closed.

Since then the news has not got any better. Politician after politician has promised the border would not return, but details have been thin on the ground.

Proposals range from the use of vehicle numberplate recognition technology and drones, right up to, in the case of Conservative MP Jacob Rees-Mogg, outright admitting to not caring about smuggling.

Rees-Mogg's suggestion has the advantage of a certain honesty, at least.

British foreign secretary Boris Johnson's comparison of the border to London's automated congestion charge scheme, on the other hand, seems to reduce what is in fact a question of contested national sovereignty to a mere technical matter.

In the spirit of Rees-Mogg's candour, let it also be said that the threat of a return to conflict in Ireland is greatly exaggerated: the IRA's three decade war with Britain was not fought over customs posts, and while the dissident Irish republican micro-groups still in existence may take pot shots at future customs posts, their strength and numbers should not be overstated.

Contested territory

Make no mistake, though, Northern Ireland remains a contested territory, and likely will long into the future.

The Belfast Agreement (usually called the Good Friday Agreement) that formally brought peace in 1998 did not bring an end to the territorial dispute, and there is a strong argument to be made that it hardened attitudes rather than softened them.

The fact is that most pro-British unionists are not particularly bothered by the reimposition of a visible border, while most pro-Irish republicans are aghast.

Any proposed solution that attempts to assuage fears immediately runs up against the hard fact that the border was always there, it simply didn't matter after 1998 because, once the militarised outposts were torn down, there was no sign left of it as the Maastricht treaty had already done away with customs posts.

Meanwhile, the authorities are now trying to map every single border crossing, suggesting at the very least some consciousness of the possibility of a closed frontier that everyone supposedly agrees cannot be allowed to happen.

The recent suggestion by British prime minister Theresa May for a deal akin to that between the US and Canada suggest something a little more intrusive than a few cameras reading car licence plates.

Undoubtedly, May meant that the use of a so-called "trusted trader scheme" meant freight could cross between the two countries without there being any sort of customs union.

Militarised border

What she apparently did not consider is that, since the 9/11 attacks, the US-Canadian border has become a heavily militarised frontier.

If this is the 'frictionless' border that British politicians have been promising since the Brexit vote, then it is a hitherto unknown usage of the word 'frictionless', and one that has not gone down well in Ireland.

Indeed, Irish prime minister Leo Varadkar immediately rejected the proposal, saying "that is definitely not a solution that we could possibly entertain". In fact, Varadkar had already put the kibosh on any such idea in 2017 during a visit to Canada.

The Irish are all for evasiveness and fudge, as befits the psychology of a post-colonial society I suppose, but the Republic of Ireland's government cannot budge on the issue as, for the Irish, EU membership means precisely the opposite to Britain.

For the Irish it means greater sovereignty, at least in a symbolic sense, where for the British it means the death of sovereignty.

When Ireland voted against the Nice and Lisbon treaties it did so conservatively: it wanted to hold-on to what it already had. So while they are unlikely candidates for 'ever closer union', the Irish are also unlikely to reject the EU in existential terms as has the UK.

In this regard, then, Ireland is the EU, and there is little room for any independent negotiation to be had.

Ireland's border woes are no reason to halt Brexit, but a sign that Britain's politicians took the problem a little more seriously would be welcome.

How the circle will ultimately be squared remains far from obvious, but imagining that political problems can be solved by technical measures is an idea Brexiteers of all people should be wary of.

After all, Brexit itself was a demand for the primacy of politics over technicalities.

Jason Walsh is an Irish journalist based in Paris.

No comments yet.

-

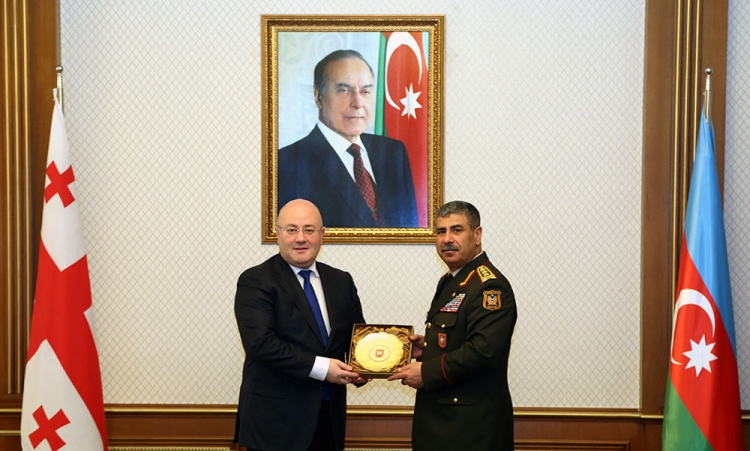

AZERBAIJAN, GEORGIA INK MILITARY CO-OP PLAN FOR 2018

The Caucasus and Turkish-Armenian Relations

12.03.2018

AZERBAIJAN, GEORGIA INK MILITARY CO-OP PLAN FOR 2018

The Caucasus and Turkish-Armenian Relations

12.03.2018

- NEW ARMENIAN OPPOSITION GROUP HOLDS RALLY IN YEREVAN The Caucasus and Turkish-Armenian Relations 12.03.2018

-

PKK TERRORISTS GIVEN 10 DAYS TO LEAVE IRAQ’S SINJAR

Iraq

12.03.2018

PKK TERRORISTS GIVEN 10 DAYS TO LEAVE IRAQ’S SINJAR

Iraq

12.03.2018

-

SRI LANKA PRESIDENT PLEDGES INQUIRY INTO RELIGIOUS RIOTS

Asia - Pacific

12.03.2018

SRI LANKA PRESIDENT PLEDGES INQUIRY INTO RELIGIOUS RIOTS

Asia - Pacific

12.03.2018

- ARMENIA'S PARLIAMENTARY DELEGATION ARRIVES IN US The Caucasus and Turkish-Armenian Relations 12.03.2018

-

25.01.2016

THE ARMENIAN QUESTION - BASIC KNOWLEDGE AND DOCUMENTATION -

12.06.2024

THE TRUTH WILL OUT -

27.03.2023

RADİKAL ERMENİ UNSURLARCA GERÇEKLEŞTİRİLEN MEZALİMLER VE VANDALİZM -

17.03.2023

PATRIOTISM PERVERTED -

23.02.2023

MEN ARE LIKE THAT -

03.02.2023

BAKÜ-TİFLİS-CEYHAN BORU HATTININ YAŞANAN TARİHİ -

16.12.2022

INTERNATIONAL SCHOLARS ON THE EVENTS OF 1915 -

07.12.2022

FAKE PHOTOS AND THE ARMENIAN PROPAGANDA -

07.12.2022

ERMENİ PROPAGANDASI VE SAHTE RESİMLER -

01.01.2022

A Letter From Japan - Strategically Mum: The Silence of the Armenians -

01.01.2022

Japonya'dan Bir Mektup - Stratejik Suskunluk: Ermenilerin Sessizliği -

03.06.2020

Anastas Mikoyan: Confessions of an Armenian Bolshevik -

08.04.2020

Sovyet Sonrası Ukrayna’da Devlet, Toplum ve Siyaset - Değişen Dinamikler, Dönüşen Kimlikler -

12.06.2018

Ermeni Sorunuyla İlgili İngiliz Belgeleri (1912-1923) - British Documents on Armenian Question (1912-1923) -

02.12.2016

Turkish-Russian Academics: A Historical Study on the Caucasus -

01.07.2016

Gürcistan'daki Müslüman Topluluklar: Azınlık Hakları, Kimlik, Siyaset -

10.03.2016

Armenian Diaspora: Diaspora, State and the Imagination of the Republic of Armenia -

24.01.2016

ERMENİ SORUNU - TEMEL BİLGİ VE BELGELER (2. BASKI)

-

AVİM Conference Hall 24.01.2023

CONFERENCE TITLED “HUNGARY’S PERSPECTIVES ON THE TURKIC WORLD"