EurActiv (22 November 2017)

With the Eastern Partnership (EaP) Summit this Friday (24 November) and the Bulgarian Presidency in January 2018, the EU is at a juncture where it can reverse a very negative trend and breathe new life in its neighbourhood policy, Harry Nedelcu writes.

Harry Nedelcu, PhD, is a policy advisor with Rasmussen Global, a Brussels-based consultancy and business advisory firm founded in 2014 by Anders Fogh Rasmussen, former Prime Minister of Denmark and former Secretary General of NATO.

Over a decade-and-a-half ago, Robert Kagan’s famous epitaph immortalised Western perceptions about the EU’s soft power. He wrote ‘Americans are from Mars, Europeans from Venus.’

Whereas the US was a hard power relying on military might, the EU epitomised the rule of law, economic prosperity, and democratic principles. Above all, the EU’s power was best observed in the way it shaped its geographic surroundings in its own image – a ‘ring of friends’ which gave globalisation endless possibilities.

At the core was the EU’s most successful foreign policy tool – conditionality – a transactional arrangement requiring painful reforms but offering an irresistible promise, membership. The countries of Central and Eastern Europe have transitioned relatively quickly and successfully in some part due to this promise.

Fast-forward 15 years and the EU today is a different political animal, one that is hardly recognisable. Instead of enlarging, it seems to be imploding. Instead of a ring of friends, it is surrounded by a ring of fire. Instead of shaping its environment, the EU seems lost and incoherent about its neighbourhood.

Enlargement fatigue in many member states make membership ever less likely for potential newcomers – and the aspirants of today are painfully aware of it. As a result, from the Western Balkans to the Eastern Neighbourhood, countries are slowly adjusting to their new political reality. In the absence of clear incentives, they are stalling and even backtracking from their past efforts.

After a great run during previous decades, the entire European project risks losing steam. Without its enlargement ambitions, with no ammunition in its conditionality toolbox, the EU is no longer the same soft-power gentle giant. Looking inwards means a smaller Europe that is less relevant.

Nevertheless, with the Eastern Partnership (EaP) Summit this November and the Bulgarian Presidency in January 2018, the EU is at a juncture where it can reverse the trend and breathe new life in its neighbourhood policy. In light of Brexit, the opportunity is ripe to showcase that EU integration is still alive. To give this recommitment real meaning, however, a few steps are key.

With respect to the Western Balkans, Bulgaria’s upcoming Presidency (together with Austria’s and Romania’s – all of which have ties to the region), should promote clear set dates with clear yet realistic benchmarks for the forerunners in the group – Montenegro, Serbia, Albania.

Instead of stating ‘not before 2025’, the EU should spell out that if these states successfully conclude negotiations and meet their respective obligations, then ‘by 2026, or 2027, they have a real chance to join’. What is important is not so much the actual year but the presence of a clear date at the political level. This would give front-runner Montenegro renewed assurances, while incentivising Albania and Serbia to do more.

On EaP, the EU needs to heed to the European Parliament and overcome its passive and inept approach of simply promoting implementation of what has already been achieved – DCFTA. While membership is a more distant prospect than in the Western Balkans, the EU needs at the very least to start a conversation about midpoints on the long road to integration.

Instead of signalling ‘no integration in sight’ it should begin talks about these midpoints – be they a Customs Union, digital union, energy union – if certain benchmarks are met on both reform and DCFTA.

In both regions, EU’s commitment can occur in two successive steps and both should be conditional on aspirants meeting a series of goals. First, a promise to commit to a target-year should be made after aspirants meet a number of preliminary benchmarks by given dates. In a second step, the target year and goal should be finally set if aspirants meet a subsequent series of benchmarks.

Following membership or deeper integration for EaP, verification and control mechanisms can be put in place that would assure sceptics like Netherlands that countries would not backtrack.

In parallel, the EU should work towards creating the political momentum favouring this direction. One avenue is to socialise both politicians and voters in Europe about the enhanced relationship with these countries and their vital role in Europe’s integration and security. For instance, this can include designating some states by different names – be it EaP+ or some other label – which, though symbolic and bearing few costs, is politically significant and acknowledges the front-runners.

Taking these steps is not easy; it will require political will and vision. Yet not taking them, deprives the EU of its most effective foreign policy tool and the main source of its soft-power.

Ultimately, the current EU is one consumed by internal issues. Yet renewed vision on integration may be the one ingredient that could turn this current episode of instability and confusion into a small glitch in what is otherwise the most ambitious collective project the continent has ever witnessed.

No comments yet.

- SYRIA, RUSSIA & IRAN SHIFT TO DIPLOMACY, WHILE US AND ALLIES PUSH FOR WAR Asia - Pacific 22.11.2017

-

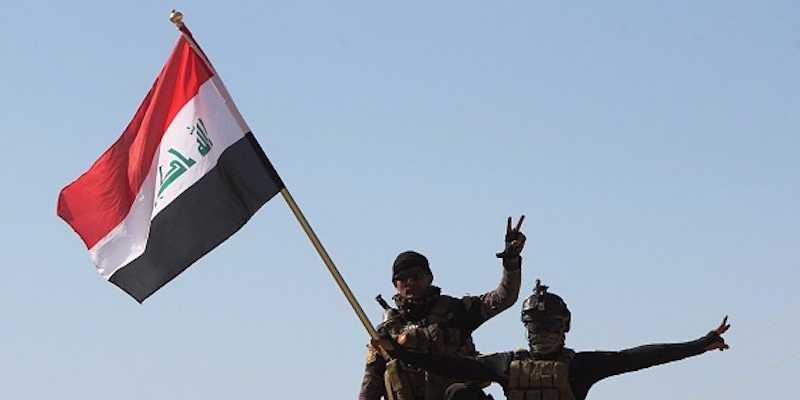

ISIS HAS BEEN MILITARILY DEFEATED IN IRAQ AND SYRIA

Iraq

22.11.2017

ISIS HAS BEEN MILITARILY DEFEATED IN IRAQ AND SYRIA

Iraq

22.11.2017

- PROSECUTORS FREEZE ROMANIAN SOCDEM LEADER’S ASSETS The Balkans 22.11.2017

- BAKU PROTESTS AGAINST VISIT OF ILLEGAL KARABAKH REGIME "HEAD" TO FRANCE The Caucasus and Turkish-Armenian Relations 22.11.2017

- GEORGIA WII-LL NOT RECOGNIZE KOSOVO, SAYS GEORGIAN PM The Balkans 22.11.2017

-

25.01.2016

THE ARMENIAN QUESTION - BASIC KNOWLEDGE AND DOCUMENTATION -

12.06.2024

THE TRUTH WILL OUT -

27.03.2023

RADİKAL ERMENİ UNSURLARCA GERÇEKLEŞTİRİLEN MEZALİMLER VE VANDALİZM -

17.03.2023

PATRIOTISM PERVERTED -

23.02.2023

MEN ARE LIKE THAT -

03.02.2023

BAKÜ-TİFLİS-CEYHAN BORU HATTININ YAŞANAN TARİHİ -

16.12.2022

INTERNATIONAL SCHOLARS ON THE EVENTS OF 1915 -

07.12.2022

FAKE PHOTOS AND THE ARMENIAN PROPAGANDA -

07.12.2022

ERMENİ PROPAGANDASI VE SAHTE RESİMLER -

01.01.2022

A Letter From Japan - Strategically Mum: The Silence of the Armenians -

01.01.2022

Japonya'dan Bir Mektup - Stratejik Suskunluk: Ermenilerin Sessizliği -

03.06.2020

Anastas Mikoyan: Confessions of an Armenian Bolshevik -

08.04.2020

Sovyet Sonrası Ukrayna’da Devlet, Toplum ve Siyaset - Değişen Dinamikler, Dönüşen Kimlikler -

12.06.2018

Ermeni Sorunuyla İlgili İngiliz Belgeleri (1912-1923) - British Documents on Armenian Question (1912-1923) -

02.12.2016

Turkish-Russian Academics: A Historical Study on the Caucasus -

01.07.2016

Gürcistan'daki Müslüman Topluluklar: Azınlık Hakları, Kimlik, Siyaset -

10.03.2016

Armenian Diaspora: Diaspora, State and the Imagination of the Republic of Armenia -

24.01.2016

ERMENİ SORUNU - TEMEL BİLGİ VE BELGELER (2. BASKI)

-

AVİM Conference Hall 24.01.2023

CONFERENCE TITLED “HUNGARY’S PERSPECTIVES ON THE TURKIC WORLD"