Deniz Ünver

Independent Researcher

We have read the recent article of Dr. Vahan Tootikian in Armenian Weekly called ¨The Armenian Press¨. Giving information on the Armenian Press, Dr. Tootikian failed to mention the Armenian Press in the Ottoman Empire in his article. This attitude of the writer indicates that Dr Tootikian contrasts with his own words in the article mentioned above, ¨Furthermore, whether independent, party owned, or partisan, the Armenian Press has a responsibility to be impartial and objective.[1]¨. It is neither impartial nor objective to not mention the Armenian Press in the Ottoman Empire and the tolerance of the Ottoman state towards the Armenian Press when writing about it. It shows behaviour signifies that Dr Tootikian is not even tolerant of the Armenian Press in the Ottoman Empire.

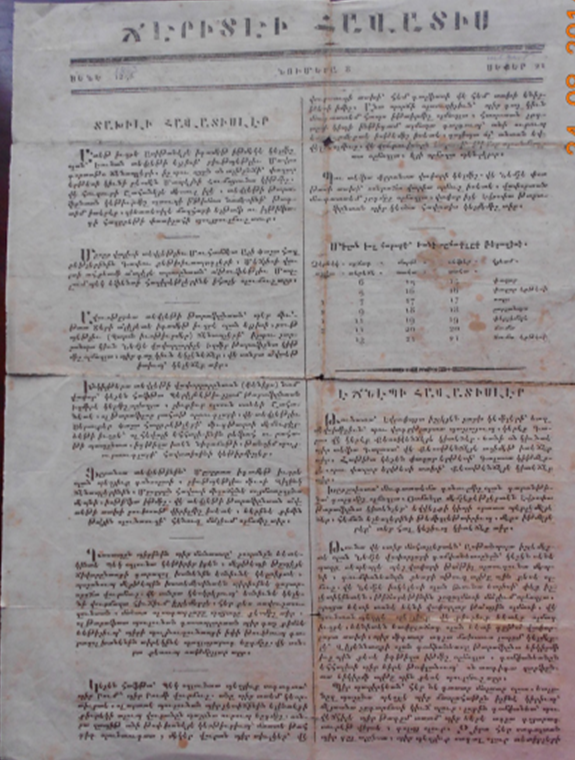

Despite being disregarded by Dr Tootikian in his article, the Armenian Press has a long history in Anatolia. The earliest traces of the Armenian Press go back to the Ottoman times. It is worth mentioning that an Armenian named Sivaslı Apkar opened a printing house in İstanbul in 1567 after learning about printing in Venice.[2]. This event started the printing life of Armenians in the Ottoman Empire.

Thus, it is noteworthy that the Ottoman State immediately published newspapers in minority languages through state media as it conducted a tolerant policy towards minority groups. Within this regard, after beginning its publishing life in Turkish on November 1, 1831, Takvim-i Vekayi, the official Newspaper of the Ottoman Empire, quickly started publishing in Armenian on January 13, 1832, among with other languages such as French, Arabic, Persian and Greek.[3]. The Armenian version of the Takvim-i Vekayi was named Liro Kir. Takvim-i Vekayi was published with Armenian letters in Ottoman Turkish. In fact, this became the characteristic of the Armenian Press in the Ottoman Empire as most of the Armenian Newspapers were published in Ottoman Turkish in Armenian alphabet.

It is worth mentioning that the Rescript of Gülhane and then the Edict of Reform provided additional rights to the non-Muslim population in the Ottoman Empire. Consequently, the Armenian Press developed further and became visible in the 19th Century.[4]. Indeed, there existed a number of Armenian newspapers in this period.

In addition to Takvim-i Vekayi or Liro Kir, the first private Newspaper, the Society of Necessary Information, began publishing in İzmir in 1839 as an extension of the Armenian Press. Society of Necessary Information was published in Armenian.[5].

Another Armenian newspaper named Azdarar Buzandyan, meaning Reporter of Byzantine, was published by Haçadur Oskanyan in 1840[6]. This Newspaper was published between 1840 and 1841[7]. Also, Ceride-i Havadis was issued in 1840 in Turkish with Armenian letters[8]. It was followed by the publication of Arpi Araratyan, meaning the Sun of Ararat, Newspaper in 1853[9]. Furthermore, Artsvi Vaspuragan, which drew attention due to its nationalist discourse, was published by Patrik Hırimyan and released between 1855 and 1863[10].

Then, on June 25, 1884, Mecmua-i Ahbar began to be published by Hovhannes Tolayan. The Newspaper, released in Armenian and Armenian in Arabic letters, targeted the Armenian Catholic Church, the Catholic Armenians in İstanbul and the Armenian Catholicos in Eastern Anatolia as its audience.[11]. Mecmua-i Anbar covered the news on Armenian Catholic society as well as the world matters[12]. It also included the letters of the Armenian citizens in Anatolia and religious discussions in its columns[13].

In 1885, Ceride-i Şarkiye, another Armenian Newspaper, was established in İstanbul in Armenian with Arabic letters[14]. Ceride-i Şarkiye, which was owned by Dikran Civelekyan and edited by Hagop Varjabedyan, Apig Mübahcıyan and Onning Balıkçıyan[15], followed a liberal discourse at its time. The Newspaper had been active between 1885 and 1913.

Moreover, Iravunk, which means right, was another part of the Armenian Press. Iravunk began publishing in 1896 in Varna and pursued a revolutionary rhetoric[16]. The Newspaper was edited by H. Boncukyan and Hagop Kırbetyan[17]. The Newspaper was released in several languages such as Armenian, Armenian with Arabic letters and in Bulgarian for a short time.

Between 1840 and 1890, there were hundreds of newspapers and journals belonging to Armenians, most of which were published either in Armenian or Ottoman Turkish with Armenian letters.[18]. Some of those publications were Mecmua-i Havâdis (1852-1877), Ahbâr-ı Konstantaniye (1855-1858), Zvarçakhos (1855-1856), Zohal (1855-1856), Cerîde-i Ticâret (1857-1858), Münâdi-i Erciyas (1859-1862), Seyhan (1860-1864), Mecmua-i Fünûn (1863), Vard Kesaryo–Gülzâr-ı Kayseriyye (1863), Orakir Hayrenyats (1863-1866), Varaka-i Havâdis (1864-1870), Rûznâme (1865), Manzume-i Efkâr (1866-1896, 1901-1917), Ararad (1869-1872, 1876), Müşveret (1870), Sedâ-yi Hakikat (1870-1873), Ser (1870), Avetaber (1872-1911), Heyal (1873-1875), Mimos (1875-1877), Moda (1875-1876), Mevsim (1874), Mamul (1876-1878), Şarivari (1876), Ruznâme-i Masis (1876-1877), Tercüman-ı Efkâr (1877-1885), Felek (1882-1887), Tohafi (1884-1885), Mecmua-yı Ahbâr (1884-1907), Cerîde-i Şarkiyye (1885-1913, 1919-1921), Musavver Cihan (1885), Ayine-i Litayif (1897), Drakhd (1909-1910)[19].

Another noteworthy example of the Armenian Press in the Ottoman era was the Jamanak Newspaper. Jamanak, which means time in English, began to be published on October 28, 1908, by Misak and Sarkis Koçunyan brothers.[20]. Jamanak is significant among the Armenian publications as it still continues its publications and is called the oldest living minority newspaper. The Newspaper still writes on topics such as politics, economics, art and sports.

However, the turning point of the Armenian Press was the period after the Second Constitutional Era. After 1909, Armenians started to publish newspapers in Anatolian cities and districts such as Van, Erzurum, Trabzon, Harput, Sivas, Tokat, Erzincan, Gevaş, Sivrihisar, İzmit, Giresun, Merzifon, Kayseri, Amasya, Antep, Konya, Samsun and İzmir.[21]. This resulted in an increase in the number of Armenian publications. By 1914, there were 39 active Armenian publications.[22]. Those publications were categorized as revolutionist, religious, pro-Tashnak, Socialist Hınchakists, Armenian nationalist and literature journals.[23]. Among those publications, there was a newspaper called Neva or Seda-yı Armenian, which was published by Mihran Apikyan (alias Mihran Mihri) and issued in Armenian in Arabic letters[24].

Those newspapers published during the Ottoman era demonstrate that the Ottoman State was tolerant towards the Armenian newspapers. Today, Jamanak and Agos are still active Armenian newspapers that continue their work in Turkish and Armenian. As a matter of fact, the Republic of Türkiye, also, pursues the same tolerant policy towards Armenians particularly signified by the Turkish tolerance towards the Armenian Press.

*Photograph: https://dergipark.org.tr/tr/download/article-file/2377321

[1] Dr. Vahan Tootikian, ¨The Armenian Press¨, The Armenian Weekly, October 18, 2023, https://armenianweekly.com/2023/10/18/the-armenian-press/?fbclid=IwAR2BbzJK7Wt934rj6kXe7g_G9ncK2AOShi9Sk0zO6yCNZ0-KXr37CiyJmDs

[2] Taşdemir, Serap, ¨Neva Yahut Seda-yı Ermeniyan Gazetesi Konusunda Notlar¨. Ankara Üniversitesi Türk İnkilap Tarihi Enstitüsü Atatürk Yolu Dergisi, 2022, p. 301.

[3] Budak, Ali, ¨XIX. Yüzyılda Osmanlı Ermeni Basını ve Devletin Rejimi Üzerine Çarpıcı Bir Polemik.¨2010. MSGSÜ Sosyal Bilimler.

[4]Taşdemir, Serap, ¨Neva Yahut Seda-yı Ermeniyan Gazetesi Konusunda Notlar¨,p. 301.

[5] Eraslan, Hülya, ¨Ermeni Basını ve Osmanlı Bankası (1896): Ceride-i Şarkiye ve İravunk Gazeteleri Arasındaki Vazife-i Sadakat ve Vazife-i İhanet Tartışması¨, Ermeni Araştırmaları, 2017, p. 121.

[6] Budak, Ali, ¨XIX. Yüzyılda Osmanlı Ermeni Basını ve Devletin Rejimi Üzerine Çarpıcı Bir Polemik.¨, 44.

[7] Ibid, p. 44.

[8] Eraslan, Hülya, ¨Mecmua-i Ahbar’da II. Meşrutiyet İlanı¨, p. 137.

[9] Çağan, Hazel. ¨Ermeni Kültürü ve Ermeni Propogandası¨. Ermeni Araştırmaları, 2013, p. 201.

[10] Taşdemir, Serap, ¨Neva Yahut Seda-yı Ermeniyan Gazetesi Konusunda Notlar¨. Ankara Üniversitesi Türk İnkilap Tarihi Enstitüsü Atatürk Yolu Dergisi, 2022, p. 302.

[11] Eraslan, Hülya, ¨Mecmua-i Ahbar’da II. Meşrutiyet İlanı¨, p. 134.

[12] Ibid, p. 134.

[13] Ibid, p. 134.

[14] Eraslan, Hülya, ¨Ermeni Basını ve Osmanlı Bankası (1896): Ceride-i Şarkiye ve İravunk Gazeteleri Arasındaki Vazife-i Sadakat ve Vazife-i İhanet Tartışması¨, p. 125.

[15] Ibid, p. 125.

[16] Eraslan, Hülya, ¨Ermeni Basını ve Osmanlı Bankası (1896): Ceride-i Şarkiye ve İravunk Gazeteleri Arasındaki Vazife-i Sadakat ve Vazife-i İhanet Tartışması¨, p. 133.

[17] Ibid, p. 133.

[18] Budak, Ali, ¨XIX. Yüzyılda Osmanlı Ermeni Basını ve Devletin Rejimi Üzerine Çarpıcı Bir Polemik.¨, 44.

[19] Budak, Ali, ¨XIX. Yüzyılda Osmanlı Ermeni Basını ve Devletin Rejimi Üzerine Çarpıcı Bir Polemik.¨, 44.

[20] ¨Jamanak 105 yaşında¨, TRT Haber, October 12, 2012, https://www.trthaber.com/haber/yasam/jamanak-105-yasinda-67454.html

[21] Taşdemir, Serap, ¨Neva Yahut Seda-yı Ermeniyan Gazetesi Konusunda Notlar¨, p. 302.

[22] Ibid, p. 304.

[23] Ibid, p. 304.

[24] Ibid, p. 300.

© 2009-2025 Avrasya İncelemeleri Merkezi (AVİM) Tüm Hakları Saklıdır

Henüz Yorum Yapılmamış.

-

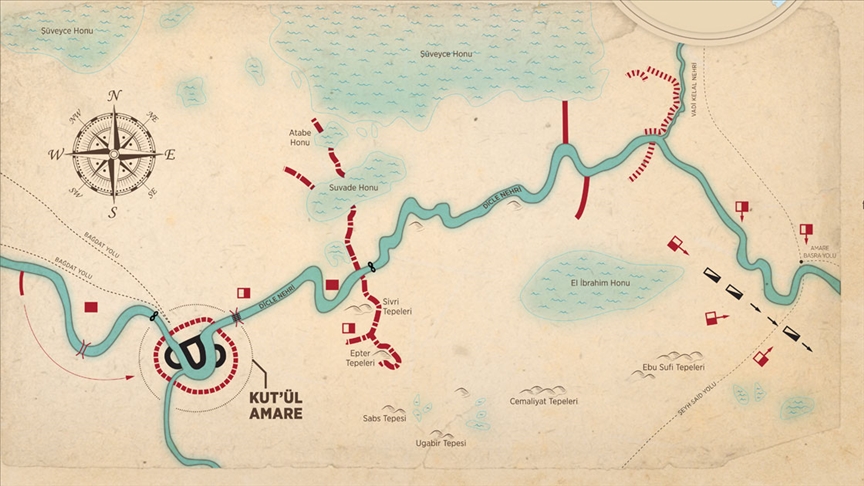

VICTORY AT KUT AL-AMARA - 27.05.2023

VICTORY AT KUT AL-AMARA - 27.05.2023

Deniz ÜNVER 27.05.2023 -

G20 AND THE MESSAGE IT CONVEYS - 29.11.2022

G20 AND THE MESSAGE IT CONVEYS - 29.11.2022

Deniz ÜNVER 29.11.2022 -

FURTHER ANALYSIS OF SINO-TURKISH RELATIONS - 10.03.2022

FURTHER ANALYSIS OF SINO-TURKISH RELATIONS - 10.03.2022

Deniz ÜNVER 10.03.2022 -

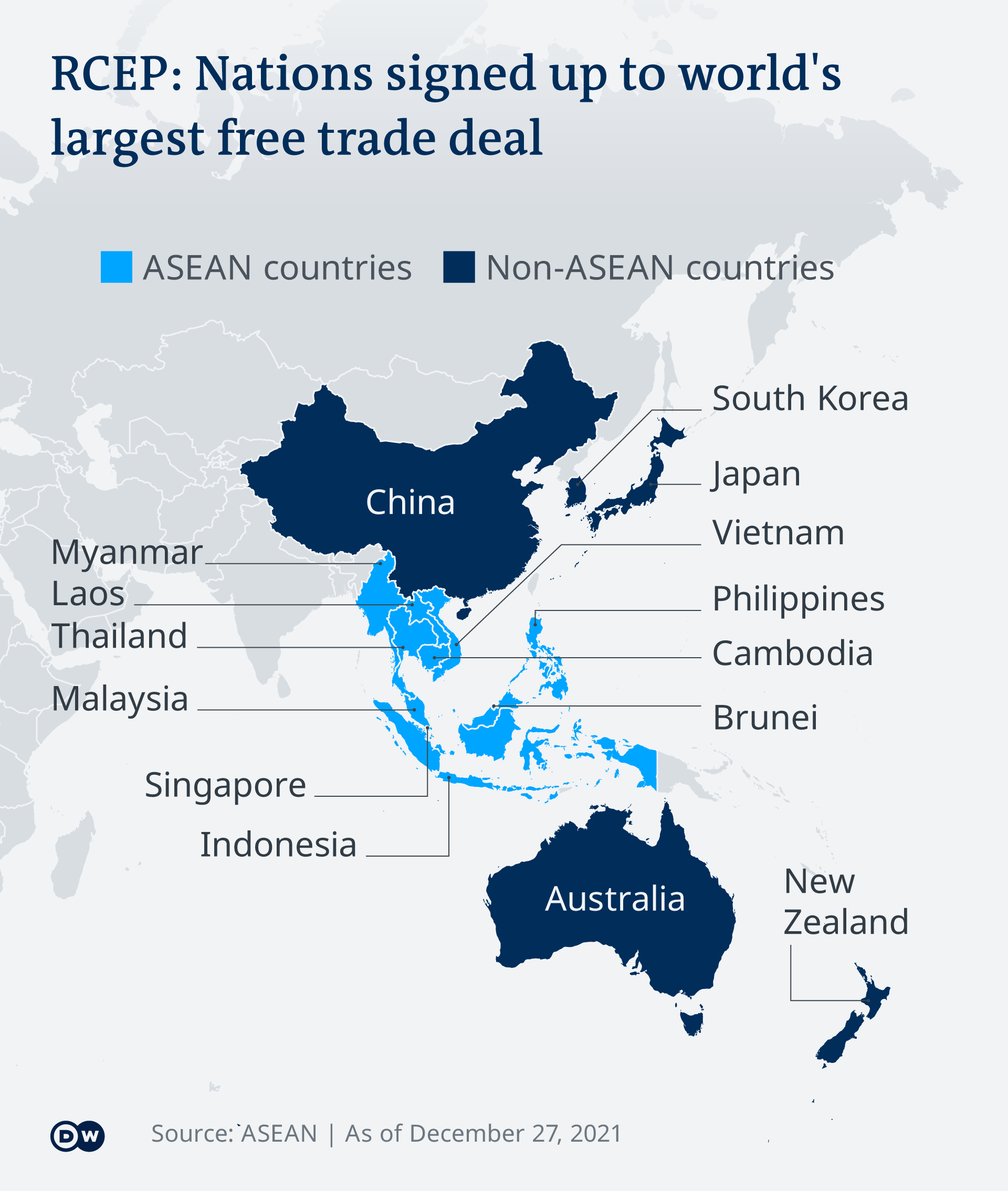

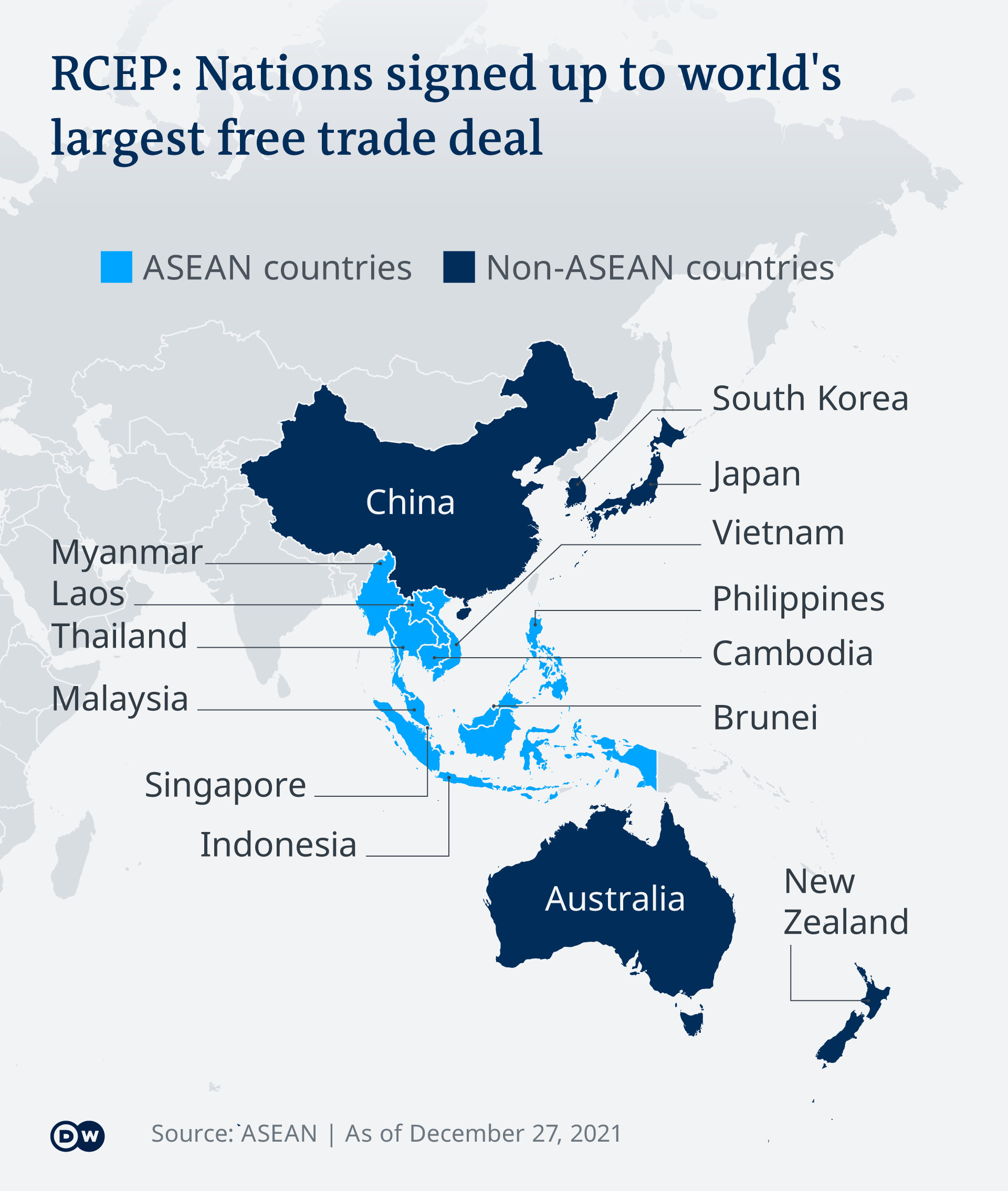

BÖLGESEL KAPSAMLI EKONOMİK ORTAKLIK (RCEP): İLAVE BİR AÇIKLAMA - 21.03..2022

BÖLGESEL KAPSAMLI EKONOMİK ORTAKLIK (RCEP): İLAVE BİR AÇIKLAMA - 21.03..2022

Deniz ÜNVER 21.03.2022 -

REGIONAL COMPREHENSIVE ECONOMIC PARTNERSHIP (RCEP): A FURTHER EXPLANATION - 10.02.2022

REGIONAL COMPREHENSIVE ECONOMIC PARTNERSHIP (RCEP): A FURTHER EXPLANATION - 10.02.2022

Deniz ÜNVER 10.02.2022

-

HOW EFFECTIVE ARE UN MISSIONS? THE CASE OF A CONTROVERSIAL UNFICYP RESOLUTION - 16.10.2023

HOW EFFECTIVE ARE UN MISSIONS? THE CASE OF A CONTROVERSIAL UNFICYP RESOLUTION - 16.10.2023

Şakir FAKILI 16.10.2023 -

YUNANİSTAN’IN VE RUMLARIN POLİTİK HÜSRANI - 26.09.2022

YUNANİSTAN’IN VE RUMLARIN POLİTİK HÜSRANI - 26.09.2022

Ata ATUN 26.09.2022 -

GAZA: THE NECESSARY GENOCIDE IN A HISTORY OF GENOCIDES - THE PALESTINE CHRONICLE - 05.01.2026

GAZA: THE NECESSARY GENOCIDE IN A HISTORY OF GENOCIDES - THE PALESTINE CHRONICLE - 05.01.2026

Jeremy SALT 05.01.2026 -

KUZEY KIBRIS TÜRK CUMHURİYETİ’NDE MARAŞ’TA YAPILACAK ENVANTER ÇALIŞMASI

KUZEY KIBRIS TÜRK CUMHURİYETİ’NDE MARAŞ’TA YAPILACAK ENVANTER ÇALIŞMASI

AVİM 05.07.2019 -

İRAN’IN NÜKLEER DOSYASINA TOPLU BAKIŞ

Ahmet ERTAY 16.11.2014