AVİM's Note: In August 2021, AVİM received a letter from Japan that was sent by Iver Torikian, an Armenian whose family once resided in Istanbul. Torikian stated that he wrote the letter because he wanted to inquire the widespread misinformation in Armenian-Turkish relations.

Originating from a scholar of Armenian background, reflecting sincere views in a free environment with an academic objectivity, AVİM has decided to publish the letter in parts over the course of several days. You can read the first part of the letter below.

Iver Torikian (August 2021)

Part One

My name is Iver Torikian. I am American. My mother was born in Germany, and my father, who is Armenian, was born in Turkey. I was born and raised mostly in the US after my parents immigrated there. Now I live in Japan.

I have visited Turkey over a dozen times during my lifetime. In Rumeli Hisarı, Istanbul, my grandparents had a house just 200 meters or so from the Bosphorus. The house was on a narrow and incredibly steep cobblestoned street. Cars painstakingly maneuvered around each other, and street peddlers walked by with their wares. I once took a photo of a man who came by with a pole across his shoulders, balancing one bucket on each end of the pole. "Yogurt, yogurt, yogurt!" he shouted.

Every morning my grandfather would wake up early and do calisthenics for an hour before going to his store near the Kapalı Çarşı. It's a routine he continued until the end of his life. His hometown was Arapkir. He had come to Istanbul by himself when he was just a boy.

My grandfather did not have an easy life. In Arapkir, when he was six, he got smallpox and was blinded in one eye. Then, after coming to Istanbul, he suffered another calamity. As a teenager, he walked the streets of Istanbul selling bread. One day he had an accident with the horse he was using and lost all his teeth. Though he was just a teenager, from that time on he had to use dentures. And yet, despite all these setbacks, he was eventually able to set up his shop and raise three sons. The eldest became my father.

My grandmother was from Gümüşhacıköy, but came to Istanbul when she was a young girl. She was the eldest of three sisters. All sisters and my grandmother came to Istanbul during the early decades of the twentieth century. Once, while I was visiting Istanbul by myself, I asked my grandmother what she had done after coming to Istanbul. She attended a madrasa, she said. Then, without any prompting from me, she demonstrated how she had learned to pray. She stood up, then kneeled down, then leaned forward, then stood up again, all while reciting prayers. It looked to me like a good exercise.

My grandmother did not choose to marry my grandfather; that decision was made for her. One day, as my grandfather was walking along a street in Istanbul selling his wares, a relative of my grandmother leaned out of the window of her house and shouted to him, "Hey, would you like a wife?" My grandfather replied, "Ah, yes, a wife would be nice." My grandmother was 19. My grandfather was in his early 30s. They got married in an Armenian church, of course, and my father was born almost exactly nine months later.

My father was lucky. My grandparents' house was within walking distance of Boğaziçi University, which was then called Robert College. My father attended junior-high school, high school, and college there. The teachers and students were of many ethnicities - "a mini UN" is how my father has described it. I have no doubt that this intermingling of teachers and students from many backgrounds was instrumental in making my father a person who is tolerant and accepting of others. Sadly, open-mindedness does not seem to be a common trait among Armenians. I have discovered over the years that many Armenians are prejudiced, particularly towards Turks.

I remember the first time I heard an Armenian telling me clearly that he did not like Turkish people. It was on the island of Kinalı, during one of my family's summer trips to Turkey when I was nine or ten years old. During that particular summer, the family of an uncle who had immigrated to Canada was also visiting Turkey. It was nice having cousins of the same age as I with whom I could converse in English. The only thing about them that bothered me was that they said bad things about Turkish people.

So, one afternoon, while were staying at the home of a relative on Kinalı, I decided to talk to one of these cousins about their anti-Turkishness. While we were walking home from the beach, I timidly asked my cousin why he disliked Turkish people. "I hate all Turkish people," he said nonchalantly. He pointed to a girl standing nearby who was wearing colorful, rustic clothing and whom neither of us knew. "You see that girl there?" my cousin said. "I hate her, because she's Turkish." I did not know what to say in response, so I said nothing.

Sadly, it is not just Armenian children like my cousin who say bad things about Turks. I know that Armenian children who disparage Turks are merely imitating Armenian adults. Once, while I was in my 20s, I went to Europe with my father and we visited Paris. My father had an Armenian friend there whom he had known when they were both growing up in Istanbul. We stayed at his house. One morning, while we were eating breakfast, the man's Armenian wife, who was also from Istanbul, began talking to me in an agitated manner. I could not understand what she was saying. As she became angrier, my father laughed nervously and explained what she wanted. She wanted me to promise her that I would never marry a Turkish woman. With the little bit of Turkish that I knew, I told her what she wanted to hear. She calmed down and we resumed breakfast.

I witnessed a third incident, worse than the two I have mentioned above, in Canada, at the home of a relative. I had wandered into the room of another cousin. He is the same age as I. On his bookshelf he had only three books, and they were all about the Second World War. Did he have an interest in history? I asked him. No, he explained, it's just that he thought Hitler did the right thing by trying to exterminate the Jewish population of Europe. It turns out that he hated Jewish people as well as Turkish people. "Jews are the small rat. Turks are the big rat," he said. No doubt he did not like rats, either.

It makes me sad to write about these incidents. Most of the Armenians I have known have been relatives, or friends of my father. Throughout my life, all have been kind to me, including the people I've mentioned above. Maybe I am just naive, but it is hard for me to understand how people can simultaneously be nice to me while hating people they have never met.

I know that I am not the only Armenian who feels this way. The Armenian journalist Hrant Dink, who was killed in 2007 in Istanbul, also rejected the anti-Turkish bitterness of Armenians. He said that it poisons us, and I agree with him.

To people who are neither Turkish nor Armenian, the animosity of Armenians towards Turks may seem inconsequential. After all, there is not going to be a war between Turkey and Armenia. Turkey dwarfs Armenia in terms of population, land, and resources, not to mention military capability. Any military conflict between Turkey and Armenia would be catastrophic for Armenia.

However, Armenians' animosity is harmful to Turks and Turkey because Armenians in North America and Europe have much political clout. Armenian groups have been attacking Turkey politically and economically for decades. For instance, Armenians in the US are always pressuring Western companies and institutions not to do business in Turkey. Some of these efforts have been successful. Also, the international Armenian community is constantly trying to persuade all the governments of the world to declare that what happened to Armenians in Turkey over a century ago was a genocide. These efforts have become known as the Armenian Cause.

Supposedly, some Armenians want only an apology from the Turkish government. Other Armenians want more, like money. And some go further; they want the Turkish government to slice off part of eastern Turkey and give it to Armenia, whereby it will become Armenian territory. Such extreme demands, of course, are ludicrous. For many reasons, I do not support any part of the Armenian Cause, even the more modest demands. They foster vindictiveness towards Turks and Turkey. Furthermore, I believe that demanding reparations and territory from the present generation of Turks -- who, needless to say, had nothing to do with the events of a century ago -- are ultimately harmful to all of humanity.

I have to confess that I still have much to learn about Armenians, and about Ottoman history. Until recently, I had very little interest in Armenian culture, history, or politics. I cannot even speak Armenian. Likewise, I had no interest in Ottoman history. Only in early 2015 did I decide to learn more about Armenians and Ottoman history, all because of an article on Armenians that appeared in the 5 January 2015 issue of a weekly American magazine called The New Yorker. It is a cultured magazine with many readers, not just in New York but all over the world. That article in the magazine was what prompted me to learn more. However, even before reading the article, I had decided to do something that would be unthinkable to most Armenians: write a letter to a US newspaper, saying that we Armenians should forgive the Turks for whatever happened long ago and seek reconciliation. I meant to do what I thought was right.

The article in The New Yorker was titled "A Century of Silence," by Raffi Khatchadourian. I had put off reading the article because I knew that it would contain stories of how Armenians had suffered, of how Armenians had been driven from villages and towns in Turkey, of how Armenians had lost possessions and livelihoods, and of how Armenians had died in great numbers. I have heard similar stories from Armenian acquaintances and relatives all my life, so I had no appetite for more.

However, one day shortly after that issue of The New Yorker reached me in Japan in early 2015, my father called me. He had heard about the article, and he asked me if I had read it. No, but I would, I said to him. So, I did. As expected, Khatchadourian told many stories of our travails, some with lurid details. But aside from mentioning the deaths of Ottoman soldiers once, Khatchadourian says almost nothing in his article about the suffering of any other people in Turkey during that era. It was clearly an entirely one-sided article.

Unfortunately, there are very few Armenian scholars who are willing to discuss the events of that era objectively. More specifically, there are few Armenians in Europe or North America who have written about the many other people in Turkey -- including Turks -- and about the turmoil and suffering that they also endured about a century ago. What is worst of all, I think, is that few Armenians in Western countries are willing to admit to non-Armenians the fact that we Armenians ourselves committed many violent acts during that period. Khatchadourian's article, for instance, contains almost nothing at all about Armenian fighters. (1/5)

© 2009-2025 Avrasya İncelemeleri Merkezi (AVİM) Tüm Hakları Saklıdır

Henüz Yorum Yapılmamış.

-

STRATEGICALLY MUM: THE SILENCE OF ARMENIANS (PART ONE) - 08.2021

STRATEGICALLY MUM: THE SILENCE OF ARMENIANS (PART ONE) - 08.2021

Iver TORIKIAN 15.11.2021 -

STRATEGICALLY MUM: THE SILENCE OF ARMENIANS (PART TWO) - 08.2021

STRATEGICALLY MUM: THE SILENCE OF ARMENIANS (PART TWO) - 08.2021

Iver TORIKIAN 18.11.2021 -

STRATEGICALLY MUM: THE SILENCE OF ARMENIANS (PART THREE) - 08.2021

STRATEGICALLY MUM: THE SILENCE OF ARMENIANS (PART THREE) - 08.2021

Iver TORIKIAN 23.11.2021 -

STRATEJİK SUSKUNLUK: ERMENİLERİN SESSİZLİĞİ (ÜÇÜNCÜ BÖLÜM) - 08.2021

STRATEJİK SUSKUNLUK: ERMENİLERİN SESSİZLİĞİ (ÜÇÜNCÜ BÖLÜM) - 08.2021

Iver TORIKIAN 23.11.2021 -

STRATEJİK SUSKUNLUK: ERMENİLERİN SESSİZLİĞİ (İKİNCİ BÖLÜM) - 08.2021

STRATEJİK SUSKUNLUK: ERMENİLERİN SESSİZLİĞİ (İKİNCİ BÖLÜM) - 08.2021

Iver TORIKIAN 18.11.2021

-

ROMANYA EKONOMİSİNDE KEMER SIKMA POLİTİKALARINA DEVAM Dr. Erhan TÜRBEDAR

- 06.12.2011 -

RAUF R. DENKTAŞ’I ANIYORUZ - HABERAYYILDIZ - 12.01.2019

RAUF R. DENKTAŞ’I ANIYORUZ - HABERAYYILDIZ - 12.01.2019

Tugay ULUÇEVİK 14.01.2019 -

SIRBİSTAN’IN YENİ HÜKÜMETİ ESKİ KONULARI TARTIŞMAYA AÇTI

Erhan TÜRBEDAR 06.08.2012 -

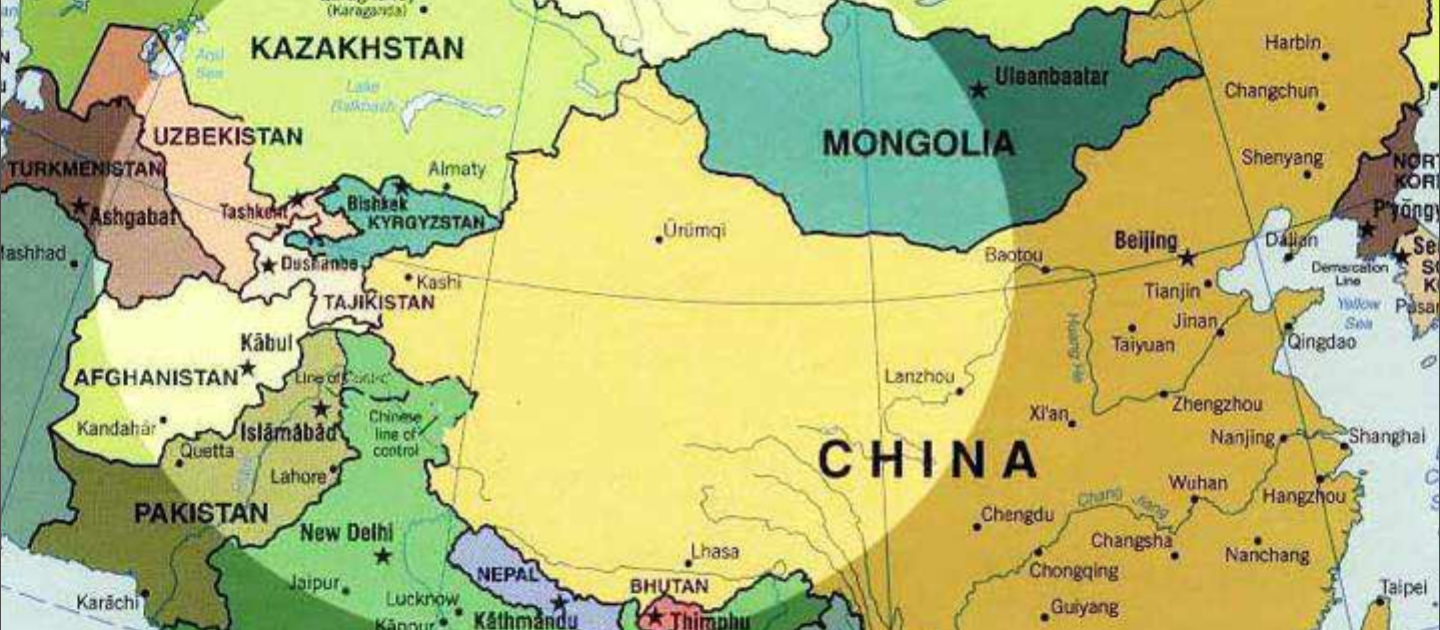

CHINA IN CENTRAL ASIA - 02.05.2023

CHINA IN CENTRAL ASIA - 02.05.2023

Deniz ÜNVER 02.05.2023 -

ORTA KORİDOR VE POTANSİYEL AVANTAJLARI - 12.10.2022

ORTA KORİDOR VE POTANSİYEL AVANTAJLARI - 12.10.2022

Deniz ÜNVER 12.10.2022