Jakub KOREJBA(*)

AVİM Intern

Government change in Italy may lead to a big discussion on the European Union’s future. One that the EU desperately needs if it wants to avoid disfunction and disintegration.

Giorgia Meloni’s victory in Italy’s parliamentary elections on 25 September has raised questions about EU’s future coherence with its third largest economy’s government becoming overtly Eurosceptical. Labelling Meloni’s party Fratelli d’Italia “populist”[1], “nationalist”[2], or even “post-fascist[3]” may be an easy way to de-legitimize its views on EU’s reality, but it will not halt discussion on EU’s future which is urgently necessary if the Union does not want to implode under the pressure of its own contradictions.

Meloni’s rise to power has all the chances to turn into epochal event in European politics as Italy,following Sweden of several weeks ago, may join the ‘illiberal bloc’ of Poland and Hungary “causing tensions that cut through the heart of the continent”[4]. Obviously, as balances of power between political parties change inside several European countries, the big discussion will also have effects at the European level. And being ‘left’ or ‘right’-oriented is not the key point here.

Putting aside specific and complex internal factors that brought Meloni to power, it is worth noticing that her ‘sceptical’ view of ‘Brussels-led Europe’ may be seen as a part of a very old discussion between two alternative and mutually exclusive visions of Europe: federal and functional.

Meloni’s criticism of EU officials[5] does not seem to signify any ‘new quality’ for EU-related discussions, that is to say, a preparation of an Italian ‘exit’ from the EU, since Meloni herself defines the future ruling party as “mainstream conservative”[6] just as Jarosław Kaczyński of Poland and Viktor Orban of Hungary do. All three leaders of governments labelled as ‘far right populists’ never overtly opted for their country’s future out of the EU. Hence, their scepticism is targeted on specific laws, institutions, and political practice established and pursued by EU’s administrative center Brussels rather than on the idea of a united Europe as such. And, as expressing those postulates leads to winning elections in several European countries, they may be seen as a legitimate part of discussion that enjoy a major popular support.

The big question behind Meloni’s victory is: in what kind of EU do we want to live? And it is this question that has not been discussed in the post-Maastricht EU at the conceptional level. During the last optimistic 30 years, mainstream political elite of virtually all EU countries lived in a Fukuyamist paradigm[7], seeing the EU as a civilizational climax and discussing basically the technical aspects of a future EU seen as a prototype of a unified European continental federation. The functionalist discourse was labelled obsolete and retrograde and any hesitation of the governments to transfer sovereign competences to Brussels was berated as ‘nationalistic’. But limiting the discussion to the only one ‘canonical’ paradigm seems counterproductive: instead of making EU stronger, it makes it internally and externally weaker and simply smaller with the United Kingdom first reaching the point of not seeing its future inside an organization which tends not to help national governments but to replace them.

Discussion between federalists and functionalists is a philosophical, if not an ideological one, thus it is impossible to say which vision of Europe is the ‘right’ one, but one cannot ignore the fact that Brussels-oriented centralization encounters explicit opposition expressed by the election results in several EU countries such as Poland, Hungary, Sweden, and Italy. This means that the path and the aim proposed by the European (Union) Commission stands in opposite to the democratic choice of at least some of European nations especially that the Commission and its policy is widely seen not as an impartial referee, but as a player in one of the national teams, a lobbyist of German interests[8].

That is why seeing Meloni’s victory through the Eurosceptical lens leads to a false perspective: when she talks against “surrendering to the bureaucrats in Brussels”[9], she really means them and not the idea of united Europe as such. If there is no democratic majority for federal Europe in Italy or Poland, it is an obvious fact that has its causes and consequences, one of them being the need for a discussion on those bureaucrats’ functions and competences. At the end of the day, if the EU wants to keep its democratic nature, it should stay evident that the people are allowed to change their bureaucrats and not vice-versa.

Italy’s election and government change may be one of the last opportunities to restart the teleological discussion within the EU to understand where we are going and keep the EU big, strong, and attractive to partners, especially those in its direct neighbourhood. The alternative is to transform the EU into a decadent, xenophobic, and dysfunctional quasi-empire led by alienated bureaucrats crushing all signs of opposition for the sake of their own ideological visions. Avoiding that is currently a central task for nations comprising the EU.

*Jakub Korejba graduated from Warsaw University (Institute of International Relations, 2009). Lecturer at MGIMO University in Moscow (2010-2015). Holds Ph.D degree (Problems of European Policy in Russia-Ukraine Relations, 2013). Journalist with several Polish newspapers and Russian TV stations.

**Photo: Claudio Peri/EFE

[3] Elections en Italie : une victoire historique pour Giorgia Meloni et l’extrême droite (lemonde.fr)

[4] Italy election: Voters poised to elect Meloni, far-right Fratelli d'Italia (The Washington Post)

[5] Italy voters shift sharply, reward Meloni’s far-right party - World News (hurriyetdailynews.com)

[7] Francis Fukuyama, The End of History and the Last Man, Free Press, 1992.

© 2009-2025 Avrasya İncelemeleri Merkezi (AVİM) Tüm Hakları Saklıdır

Henüz Yorum Yapılmamış.

-

A ‘BLINK’ MOMENT OF THE RUSSIA-UKRAINE WAR - 15.10.2025

A ‘BLINK’ MOMENT OF THE RUSSIA-UKRAINE WAR - 15.10.2025

Jakub KOREJBA 15.10.2025 -

WESTERN POLITICS IN THE SOUTH CAUCASUS: A STRATEGIC CHOICE OR A TACTICAL GAME? - 14.03.2024

WESTERN POLITICS IN THE SOUTH CAUCASUS: A STRATEGIC CHOICE OR A TACTICAL GAME? - 14.03.2024

Jakub KOREJBA 14.03.2024 -

TÜRKİYE AND POLAND - A GEOPOLITICAL COMEBACK? - 17.10.2022

TÜRKİYE AND POLAND - A GEOPOLITICAL COMEBACK? - 17.10.2022

Jakub KOREJBA 17.10.2022 -

REFERENDUMS - A GAME CHANGER BETWEEN RUSSIA AND UKRAINE - 11.10.2022

REFERENDUMS - A GAME CHANGER BETWEEN RUSSIA AND UKRAINE - 11.10.2022

Jakub KOREJBA 11.10.2022 -

TÜRKİYE AND EASTERN EUROPE - PROSPECTS AND LIMITS

TÜRKİYE AND EASTERN EUROPE - PROSPECTS AND LIMITS

Jakub KOREJBA 06.10.2022

-

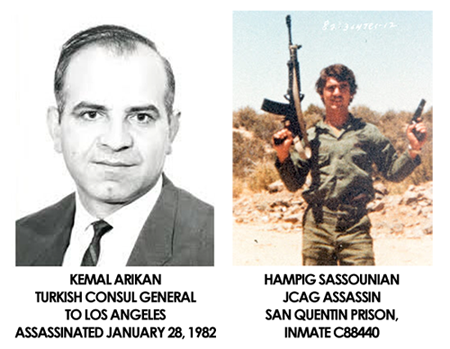

REVERSALS OF RESOLUTIONS ON 1915 EVENTS

REVERSALS OF RESOLUTIONS ON 1915 EVENTS

Turgut Kerem TUNCEL 28.11.2016 -

EARLY PAROLE HEARING FOR ARMENIAN TERRORIST IN US DENIED – DAILY SABAH – 01.08.2019

EARLY PAROLE HEARING FOR ARMENIAN TERRORIST IN US DENIED – DAILY SABAH – 01.08.2019

Daily Sabah 01.08.2019 -

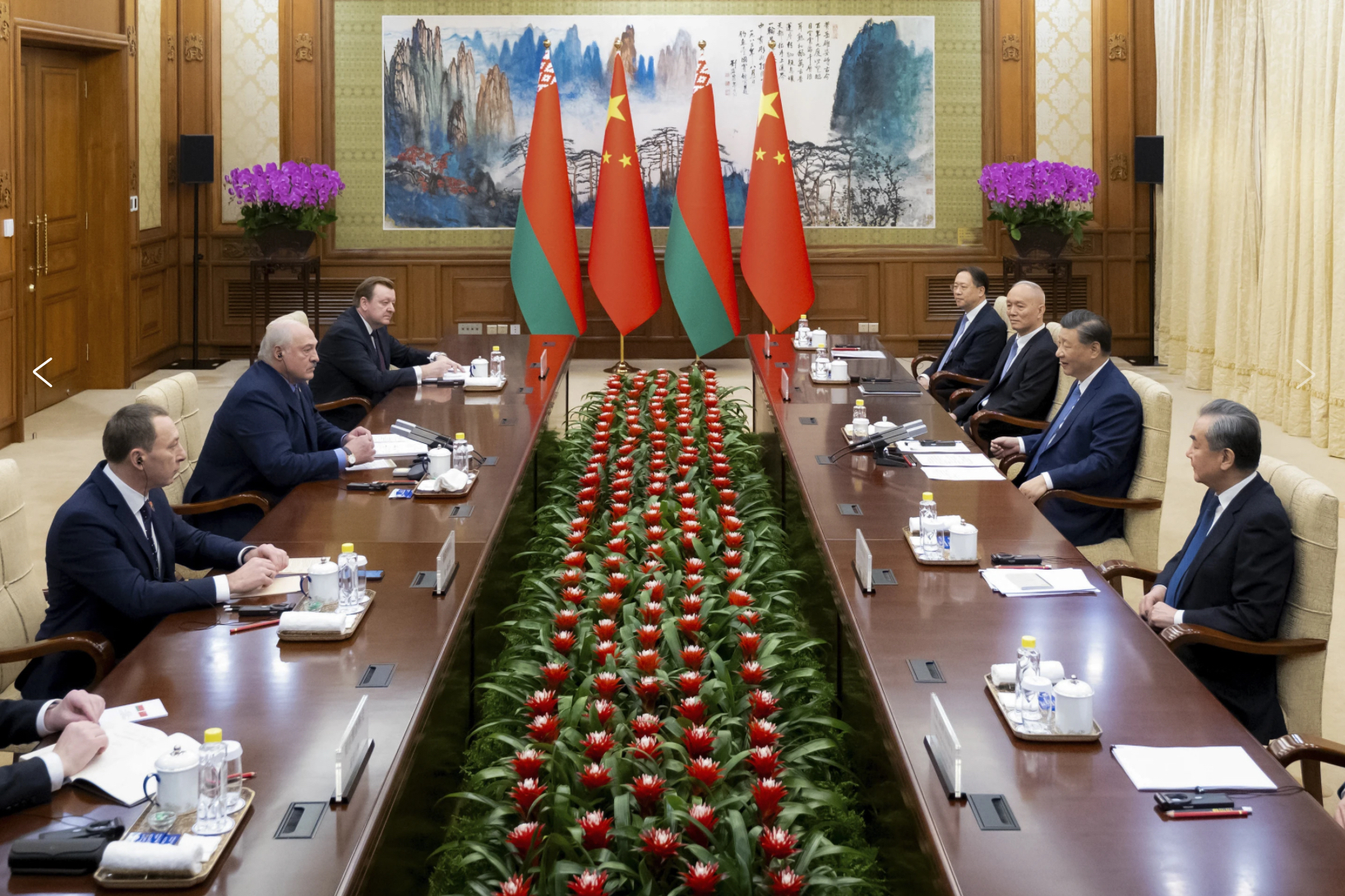

BELARUS-CHINA RELATIONS AMID GEOSTRATEGIC CHALLENGES - 08.02.2024

BELARUS-CHINA RELATIONS AMID GEOSTRATEGIC CHALLENGES - 08.02.2024

Yauheni PREIHERMAN 08.02.2024 -

HEDEF EL HAŞİMİ Mİ, KERKÜK MÜ?

Mehmet KANCI 12.09.2012 -

“SOYKIRIMI İNKAR YASASI”NIN YARATTIĞI ÇİFTE KRİZ" - SÖYLEDİK - 15.02.2018

“SOYKIRIMI İNKAR YASASI”NIN YARATTIĞI ÇİFTE KRİZ" - SÖYLEDİK - 15.02.2018

Deniz BERKTAY 16.02.2018