Jakub KOREJBA(*)

AVİM Intern

As Eurasian Heartland loosens its grip on the former rims, neighbourhooding regional powers are confronted by the need of a proactive strategy. Individually or collecitvely, they will have no choice but to manage the post-Soviet space.

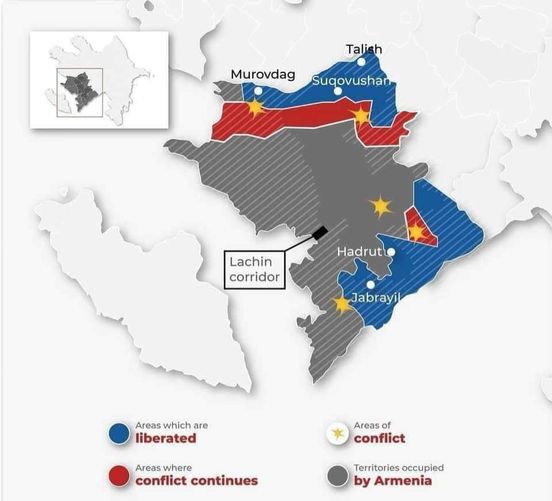

After more than six months from the beggining, it’s already obvious that the Russian ‘special operation’ did not go according to the plan, this fact already has and will have consequences far beyond the occupied regions of Ukraine. As a result, regional order entered a period of dynamic modification, not only on the Western flank of Russian zone of interest but along all post-Soviet borders between Russia and former Soviet Republics, including South Caucasus and Central Asia. Tensions between Azerbaijan and Armenia on one side and Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan on the other as well as a very evident change of roles and hierarchies between members and guests of Shanghai Cooperation Organization demonstrated during the Samarkand summit show that as a prominent Russian expert euphemistically admitted: “the usual scheme of globalization has ceased to work, and the new one will be based on regional links”[1]

Leaving aside objective (structural trends) and subjective (decisions of individuals) reasons and exact timing of these changes, it may be stated that the intended extension of Russian power projection to the West, results in its antithesis: all along Russian borders, starting in the Far North and Scandinavia, through Eastern Europe, Caucasus to Central Asia, the former dominant power is in retreat, zones of no-interest (‘grey zones’) are shrinking, neutral states choose to reinforce their ties with alternative allies or/and form regional alliances outcoming in an ubiquitous reverse of strategic vectors: former Russian zone of interest ceases being Moscow-centric and thus becomes geopolitically ‘open’ and ready to receive influence from beyond. All those factors stimulate new regional leading states to emerge and take responsibility for the transition process as well as an elaboration of a perspective proposal.

As François Rabelais said, nature abhors a vacuum and so does the international system. Russian mismanagement of its neighbourhood confronts neighbours from the other side with a necessity to act regardless of their own will to do that because the governments and societies of the ex-Soviet republics not just call them to do it but simply behave in a way that requires not only a reaction but a whole coherent strategy (e.g.: massive flood of Ukrainian refugees to Poland, the Armenian-Azerbayjani or Kyrgyz-Tajik escalations). As George Friedman quite prophetically put it already in 2009, the consequences of a decadence of Russian influence on its former satellites will lead to form “an unexpected coalition from Eastern Europe, Eurasia, and the Far East[2]” with Poland, Turkey and China compelled to take the responsibility for processes spontaneously unfolding in the post-Soviet regions adjacent to them, specifically Eastern Europe, South Caucasus and Central Asia of which they have to take care due to a very objective und unavoidable factor such as geographical proximity[3].

Although very far from each other from many different points of view, Poland, Turkey and China obviously share one thing in common: all three are immediately and directly affected by the fact that Russia ceases to be an attractive pole of power for its post-Soviet ex-satellites. Regardless of the reasons of Russian decline which may differ in all three regions, the result for emerging regional leaders is the same in all three: they all have to assume responsibility of, firstly, ending the ongoing conflicts by a durable peace solution, and, secondly, elaborate a realistic development agenda for the post-conflict period and all that in a context of vast uncertainty of the level and timing of influence of a fading but still present Russian factor. In this regard, levels of engagement and results differ: Turkey is successively stabilizing South Caucasus, Poland tries to shape its own and EU’s policy towards Ukraine and China seems to avoid announcing its direct responsibility in Central Asia relaying on a ‘soft’ instruments.

But as Robert Kaplan puts it, geography will take revenge, and non-having a strategy towards the biggest post-imperial entity in Eurasia if one is its direct neighbour, may only result in being forced to sooner or later bear the consequences of its implosion by improvised means.

No formal coalition is neither possible nor needed but a certain level of coordination and mutual experience-sharing would certainly enhance the process of peace-making and fasten construction of a new order on the three edges of Eurasia. A durable and profitable one, also for Russian relations with its neighbours, once the actual political cycle comes to an end and the next one starts in a new configuration of forces.

Having in mind failures and omissions already made, which become obvious at the point when they lead to open conflicts, the ultimate aim is to not let the ‘Global Balkans’[4] degenerate into a source of a wider global conflict, that is to say to avoid the Third World War, which is already and hopefully prematurely announced as a matter of fact[5].

Stabilization of the former post-Soviet area, it’s reconstruction and transformation towards a new model of development inside countries and a new model of interaction between them will rely first and foremost on its direct neighbours, who have no choice but to act proactively as those who will be first affected in case if the internal dynamics of post-Soviet zone goes out of control. In this regard, Turkey seems to be the central edge of the Eurasian triangle, as its interests are present not only in South Caucasus but in Central Asia and Eastern Europe as well. From the Polish perspective, Turkish potential, experience, its cultural and geopolitical know-how are more than welcome in the prospect of the common effort to shape a new, peaceful, stable and prosperous regional order.

(*) Jakub Korejba graduated from Warsaw University (Institute of International Relations, 2009). Lecturer at MGIMO University in Moscow (2010-2015). Holds Ph.D degree (Problems of European Policy in Russia-Ukraine Relations, 2013). Journalist with several Polish newspapers and Russian TV stations.

[1] Федор Лукьянов, «Привычная схема глобализации перестала работать, а новая будет основана на региональных звеньях, ШОС – идеальная опора» — Россия в глобальной политике (globalaffairs.ru), https://globalaffairs.ru/articles/shos-idealnaya-opora/

[2] George Friedman, The Next 100 Years: A Forecast for the 21st Century, Doubleday, 2009.

[3] Robert D. Kaplan, The Revenge of Geography, Random House, Inc., 2012.

[4] Zbigniew Brzezinski, The Grand Chessboard: American Primacy and Its Geostrategic Imperatives, Basic Books, 1998.

[5] Dugin: World War 3 Is Coming. Putin's favorite ideologue calls for total mobilization of Russia against decadent West, Dugin: World War 3 Is Coming - The American Conservative

© 2009-2025 Avrasya İncelemeleri Merkezi (AVİM) Tüm Hakları Saklıdır

Henüz Yorum Yapılmamış.

-

HUNTINGTON REVERSED: HOW TURKISH MEDIATION BETWEEN RUSSIA AND UKRAINE FALSIFIES THE ‘CIVILIZATIONAL’ PARADIGM OF INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS - 21.05.2025

HUNTINGTON REVERSED: HOW TURKISH MEDIATION BETWEEN RUSSIA AND UKRAINE FALSIFIES THE ‘CIVILIZATIONAL’ PARADIGM OF INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS - 21.05.2025

Jakub KOREJBA 22.05.2025 -

TURKISH RELATIONS WITH EUROPEAN UNION - BETWEEN EXPECTATIONS AND REALITY - 26.05.2023

TURKISH RELATIONS WITH EUROPEAN UNION - BETWEEN EXPECTATIONS AND REALITY - 26.05.2023

Jakub KOREJBA 26.05.2023 -

WESTERN POLITICS IN THE SOUTH CAUCASUS: A STRATEGIC CHOICE OR A TACTICAL GAME? - 14.03.2024

WESTERN POLITICS IN THE SOUTH CAUCASUS: A STRATEGIC CHOICE OR A TACTICAL GAME? - 14.03.2024

Jakub KOREJBA 14.03.2024 -

MEETING IN WASHINGTON - A LESSON OF REALISM - 22.08.2025

MEETING IN WASHINGTON - A LESSON OF REALISM - 22.08.2025

Jakub KOREJBA 25.08.2025 -

RUSSIA AND UKRAINE: FAR FROM PEACE - 27.09.2022

RUSSIA AND UKRAINE: FAR FROM PEACE - 27.09.2022

Jakub KOREJBA 27.09.2022

-

ON DEVEDJIAN’S PASSING - 10.04.2020

ON DEVEDJIAN’S PASSING - 10.04.2020

Pulat TACAR 14.04.2020 -

SPEECH DELIVERED BY IHRA PRESIDENT AMBASSADOR AYLİN TAŞHAN ON INTERNATIONAL HOLOCAUST REMEMBRANCE DAY

SPEECH DELIVERED BY IHRA PRESIDENT AMBASSADOR AYLİN TAŞHAN ON INTERNATIONAL HOLOCAUST REMEMBRANCE DAY

Aylin TAŞHAN 27.01.2017 -

AN END TO THE ARMENIAN OCCUPATION OF KARABAKH IS THE ONLY HOPE FOR PEACE AND STABILITY IN THE REGION (UPDATED) - DRPATWALSH.COM - 10.10.2020

AN END TO THE ARMENIAN OCCUPATION OF KARABAKH IS THE ONLY HOPE FOR PEACE AND STABILITY IN THE REGION (UPDATED) - DRPATWALSH.COM - 10.10.2020

Pat WALSH 16.10.2020 -

ERDOGAN'S OFFICIAL VISIT TO BELGRADE - THE GOLDEN AGE OF BILATERAL RELATIONS - MEDIUM - 06.11.2024

ERDOGAN'S OFFICIAL VISIT TO BELGRADE - THE GOLDEN AGE OF BILATERAL RELATIONS - MEDIUM - 06.11.2024

Jelena Andjelkovic 06.11.2024 -

ALMANYA’NIN AMACI NE? - TÜRKİYE GAZETESİ - 05.06.2016

ALMANYA’NIN AMACI NE? - TÜRKİYE GAZETESİ - 05.06.2016

Prof. Dr. Çağrı ERHAN 30.06.2016