Tal BUENOS

Daily Sabah, 11.09.2014

As Raphael Lemkin's studies on the concept of 'genocide' acutely reveal, political motivations often overshadow the integrity and impartiality of academic endeavors. This fact has recurred in many case studies including the Turkish-Armenian conflict.

Armenian suffering, past or present, is not really at the core of Perinçek v. Switzerland. The question of how to characterize certain historical events almost a century after is not a matter upon which courts of law - not even the Grand Chamber of the European Court of Human Rights - may decide. However, the very existence of this question is a symptom of a larger and more important question that the court cannot ignore, though it might disregard: why did Switzerland strip a Turk of his freedom of expression and criminalize his opinion regarding an ongoing historical debate of political significance? It is the task of the honored judges of the court to weigh in on how the law and its interpretation in Switzerland may reflect dangerous political and social conditions in Europe for people who are Turkish, Muslim, or both.

The recruitment of Raphael Lemkin's name and views as a tool to promote accusations of genocide against Turks is one of the clearest indications that the so-called historical engagement is a façade for a long-running anti-Turkish campaign. Thanks to the availability of the Raphael Lemkin papers at the Manuscripts and Archives Division of the New York Public Library, it may be ascertained that Lemkin considered dozens of cases to be genocide.

In the late 1950s, some years after his employment by the U.S. government and involvement in the U.N. Genocide Convention, Lemkin attempted to develop and promote "genocide" independently by writing a book under the title "Introduction to the Study of Genocide." It may be argued that he wanted to publish this book to highlight the "moral preventive force of the Genocide Convention," but it is evident that his own prestige depended on the worldwide popularity of the term that became associated with his name. While the book was never published, the book proposal shows his efforts to widen the applicability of the term by listing a total of 62 cases of genocide in antiquity, the Middle Ages, and modernity. Of the 41 cases in modern times, number 39 states "Armenians." Number nine on that list is "Genocide by the Greeks against the Turks." For instance, the Lemkin papers show that he had 100 pages on the case of "Belgian Congo" and 98 pages on the "Genocide against the American Indians."

This does not mean that they were all genocides. Article 2 of the Genocide Convention defines genocide according to a particular "intent to destroy," as opposed to an intent to defend against a rebellion or settle political disputes. Article 6 of the Genocide Convention specifies that a charge of genocide is made in legal contexts and determined by a particular "competent tribunal," as opposed to personal opinion, be it Lemkin's or anyone else's. Lemkin developed a broad view of what should count as genocide - a view that does not coincide with the wording in the Genocide Convention. It also means that, despite common depictions, Lemkin did not reserve a special place for the Armenian tragedy.

"Axis Rule in Occupied Europe," the book that was published under Lemkin's name in 1944 by the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, and in which "genocide" was coined, lists several instances of genocide without a single mention of Armenians. Interestingly, instances that are described as genocide in the book are not on the lips of those who claim to know what Lemkin had in mind in 1944. Much of what Lemkin had to say publicly about genocide was affected by considerations of time and place - and audience and purpose. While he was associated with many Christian organizations in the U.S., he gave an interview to CBS in 1949 and stated that he became interested in genocide because of what happened to Armenians. However, while he was campaigning for genocide ratification in Italy, his answer to the question: "When did you first become interested in Genocide?" was Armenian-free: "From my very young days when I read the book "Quo Vadis" by Sienkiewicz as a Polish school boy, about the destruction of the early Christians by the Roman emperors. I asked my mother why the Christians did not call the police. She said that the police couldn't help them since Nero was in the arena. She gave me books to read on cases of genocide such as Carthage, and the Mongol invasions. I devoured these books and became so interested in the problem that I made a vow as a child to become a lawyer and to make a law to prevent reoccurrences of these acts."

In similar fashion, his autobiography, which was rejected by publishers in the 1950s due to lack of public interest, yet recently published due to the influence of genocide scholars, was designed to describe his life in purely genocide-oriented terms while his unaffected resume shows that in the years of 1929 to 1939 he was a professor of family law at a college in Poland, which seems to have little to do with an expertise in international law.

The Lemkin papers also show that, due to his overall aim to refer to many cases as genocide and his lack of focus on any particular case, his research on Armenian suffering was not based on a thorough study of primary sources, as one might expect of an academic scholar. Rather, his findings were largely based on the writings of Arnold J. Toynbee, who was a young historian employed by the British government to generate propaganda while Britain was at war with the Ottoman state, and the U.S. ambassador in Constantinople, Henry Morgenthau, who functioned as a representative of entente interests at the beginning of the war while being aided by an Armenian legal advisor, Arshag Schmavonian, and an Armenian private secretary, Hagop Andonian. What academic institution today would award a doctoral degree to a candidate whose dissertation treats information that is based on similarly biased sources as facts?

Within Lemkin's research papers there is one passage - probably written by his assistant - that expresses thoughts of accusing Mustafa Kemal Atatürk of genocide against Turks: "When one considers Atatürk's Westernization process of Turkey, one wonders just what does constitute cultural genocide. Obviously, Atatürk was committing genocide on his own people's culture." It is this type of genocide-drunkenness that has tampered with the past sobriety of simply meaning to prevent another Holocaust from ever happening again.

William Schabas stated in the Journal of Genocide Research during his tenure as president of the International Association of Genocide Scholars that " Courts are no more interested in what Lemkin thought about the scope of the term genocide than they are in what Kant or Montesquieu thought about murder and rape. It's not really relevant . Preventing and prosecuting genocide is not about fidelity to the original vision of Raphael Lemkin. His 1944 book is not our gospel." Why is it, then, that Lemkin's authority is unchallenged as part of a narrative that accuses Turks of genocide in Switzerland?

In Switzerland, the public and the government are under the influence of misconceptions on Lemkin. This might have much to do with the fact that school children in Switzerland are taught, regardless of facts showing otherwise, that Armenian suffering in World War I served as a foundational inspiration for the coining of the term genocide.

Facing History and Ourselves, which is self-described as "an international educational and professional development organization," was founded in 1976 in Brookline, Massachusetts, and claims to reach over 1.5 million middle and high school students through more than 19,000 educators in the U.S. and Switzerland. This organization's teachings, in consultation with Armenian-American scholars Richard Hovannisian and Peter Balakian, construct a narrative that politicizes world history and is markedly Armenian-centered.

Lemkin's many genocides are proof that his opinion should not cast a shadow on proper historical inquiry and the strict legal definition of genocide. Moreover, many genocides of Lemkin are proof that whoever singles out the Ottoman-Armenian conflict as the one inspirational case in the history of genocide is doing so for political interests that seek to exploit and expand the existence of prejudice against the Turkish people in Europe.

The Grand Chamber that is about to review Perinçek v. Switzerland might not be able to stop an anti-Turkish historical revision from happening, but might acknowledge that it is happening.

* M.A. in Theological Studies from Harvard Divinity School, and is currently a Ph.D. candidate in Political Science at the University of Utah

http://www.dailysabah.com/opinion/2014/09/11/many-genocides-of-raphael-lemkin

© 2009-2025 Avrasya İncelemeleri Merkezi (AVİM) Tüm Hakları Saklıdır

Henüz Yorum Yapılmamış.

-

THE PUPPET POPE

Tal BUENOS 13.10.2015 -

THE RIGHT TO REFUTE

Tal BUENOS 24.04.2014 -

TAL BUENOS’ COMMENTARY ON THE BACKGROUND OF THE GENOCIDE HYPOTHESIS

Tal BUENOS 06.07.2015 -

THE ADDRESS DELIVERED BY TAL BUENOS NSW PARLIAMENT

THE ADDRESS DELIVERED BY TAL BUENOS NSW PARLIAMENT

Tal BUENOS 08.12.2014 -

ERMENİ TARİHİNİN ULUSLARARASI SİYASET BOYUTU

Tal BUENOS 01.05.2014

-

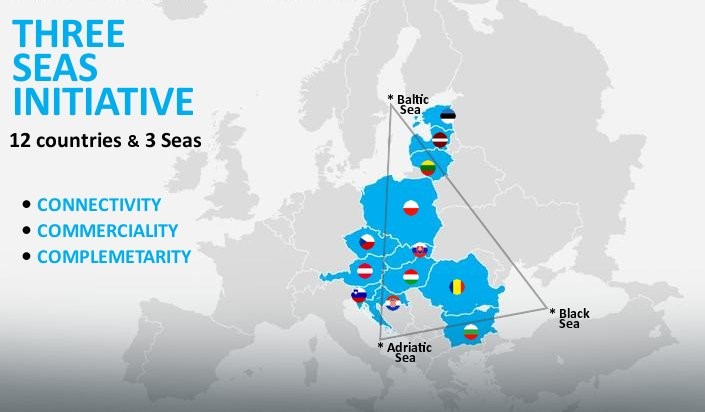

ÜÇ DENİZ GİRİŞİMİ (ÜDG): BATI'NIN BÜYÜK GÜÇ REKABETİ HAMLESİ-06.03.2023

ÜÇ DENİZ GİRİŞİMİ (ÜDG): BATI'NIN BÜYÜK GÜÇ REKABETİ HAMLESİ-06.03.2023

Deniz ÜNVER 06.03.2023 -

DEPREM, TÜRK CUMHURİYETLERİNİN TOPLUMSAL DUYGUDAŞLIĞI VE KAZAK GÖNÜLLÜLERLE MÜLAKAT - 14.03.2023

DEPREM, TÜRK CUMHURİYETLERİNİN TOPLUMSAL DUYGUDAŞLIĞI VE KAZAK GÖNÜLLÜLERLE MÜLAKAT - 14.03.2023

Alparslan ÖZKAN 14.03.2023 -

WHY EUROPE SHOULD SUPPORT PEACE IN THE SOUTH CAUCASUS - AIIA - 07.06.2024

WHY EUROPE SHOULD SUPPORT PEACE IN THE SOUTH CAUCASUS - AIIA - 07.06.2024

Taras KUZIO 10.06.2024 -

BLACK SEA ECONOMIC COOPERATION AND SECURITY IN THE BLACK SEA: IN VIEW OF THE DRONE CONFLICT BETWEEN RUSSIA AND THE US - 24.03.2023

BLACK SEA ECONOMIC COOPERATION AND SECURITY IN THE BLACK SEA: IN VIEW OF THE DRONE CONFLICT BETWEEN RUSSIA AND THE US - 24.03.2023

Deniz ÜNVER 24.03.2023 -

ARMENIANS’ TRUE MOTIVES BEHIND FALSIFICATION OF HISTORICAL TRUTHS

ARMENIANS’ TRUE MOTIVES BEHIND FALSIFICATION OF HISTORICAL TRUTHS

Arastu HABİBBEYLİ 02.07.2018